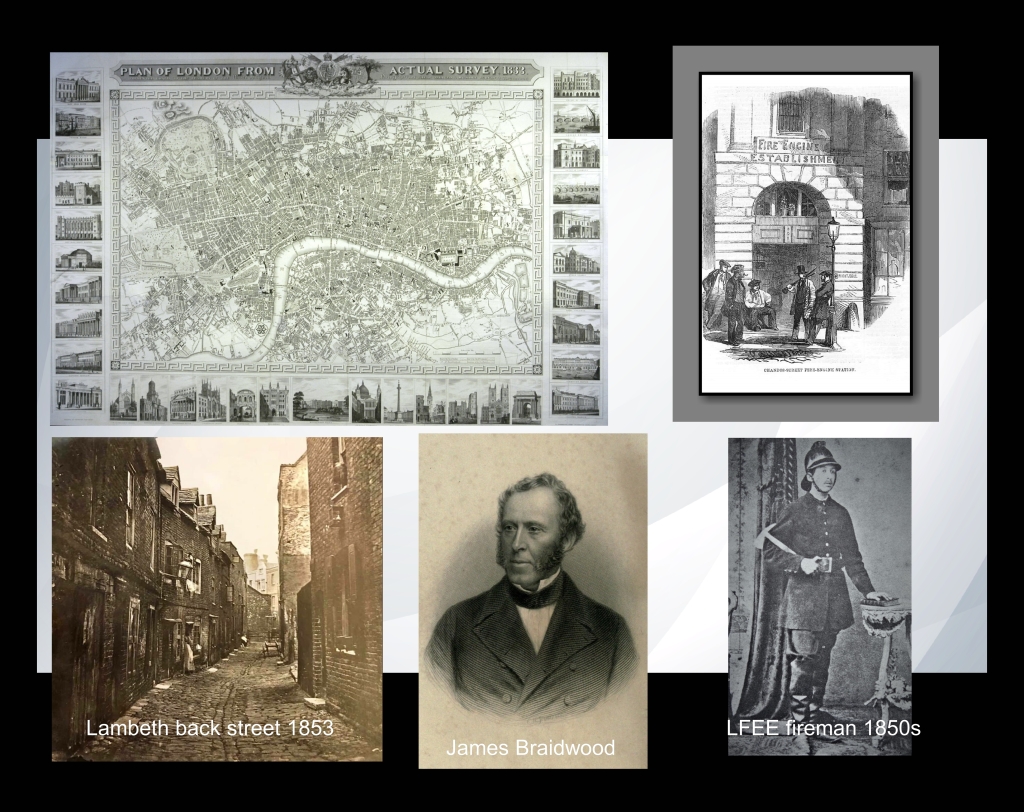

It had taken the insurance companies a whole year to come together to form one London wide fire brigade, the London Fire Engine Establishment (LFEE). The Brigade came into force in January 1833. This amalgamation of the former insurance brigades helped to remove some of the chaos that had up to then been occurring at fires. It was the capital’s first unified fire brigade.

The London Fire Engine Establishment’s (LFEE) first Superintendent was to be James Braidwood. He had been enticed to come to London to lead this new brigade at a salary of £400.00 p.a. Most of the London insurance companies saw the benefit of mutual co-operation, and the successful working of the fire brigade force in Edinburgh. Braidwood was their natural choice to command the London Fire-Engine Establishment.

Initially the companies to combine were the: Alliance, Atlas, Globe, Imperial, London Assurance, Protector, Royal Exchange, Sun, Union, and Westminster. They were later joined by the: British, Guardian, Hand-in-Hand, Norwich Union, and Phoenix. Only two fire-offices from London chose not to be involved with the LFEE. The insurance brigades, had amalgamated under the LFEE banner with the Brigade managed by a Committee comprising of a director from each of the contributing fire offices.

This Insurance Companies Committee, who paid for LFEE in agreed proportions, divided London into four fire districts. They were:

1st, eastward of Aldersgate Street and St. Paul’s.

2nd, westward to Tottenham Court Road and St. Martin’s Lane.

3rd, all westward of the 2nd district.

4th, south of the river.

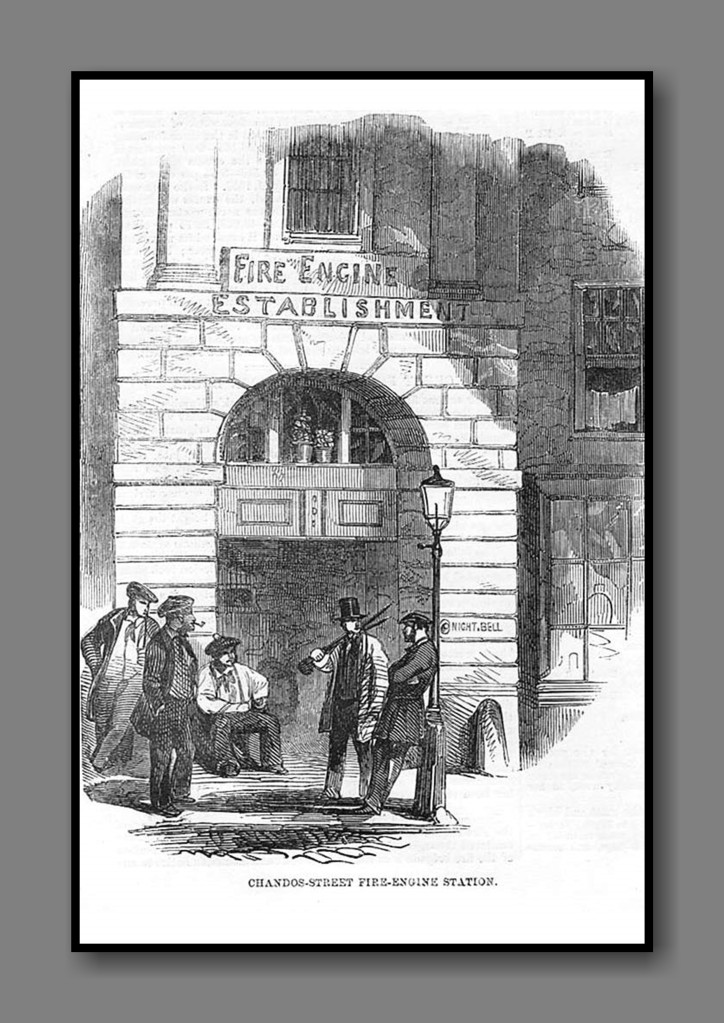

In each of four districts the Committee established fire engine stations with about three stations to each district. At each station were one, two, or three engines, according to the importance of the station. The most easterly station was at Ratcliff, and the most western near Portman Square. At these stations were the total brigade complement of thirty-five engines and the brigade’s force of around ninety men under the sole direction of the Brigade’s Superintendent Braidwood. There was no deputy.

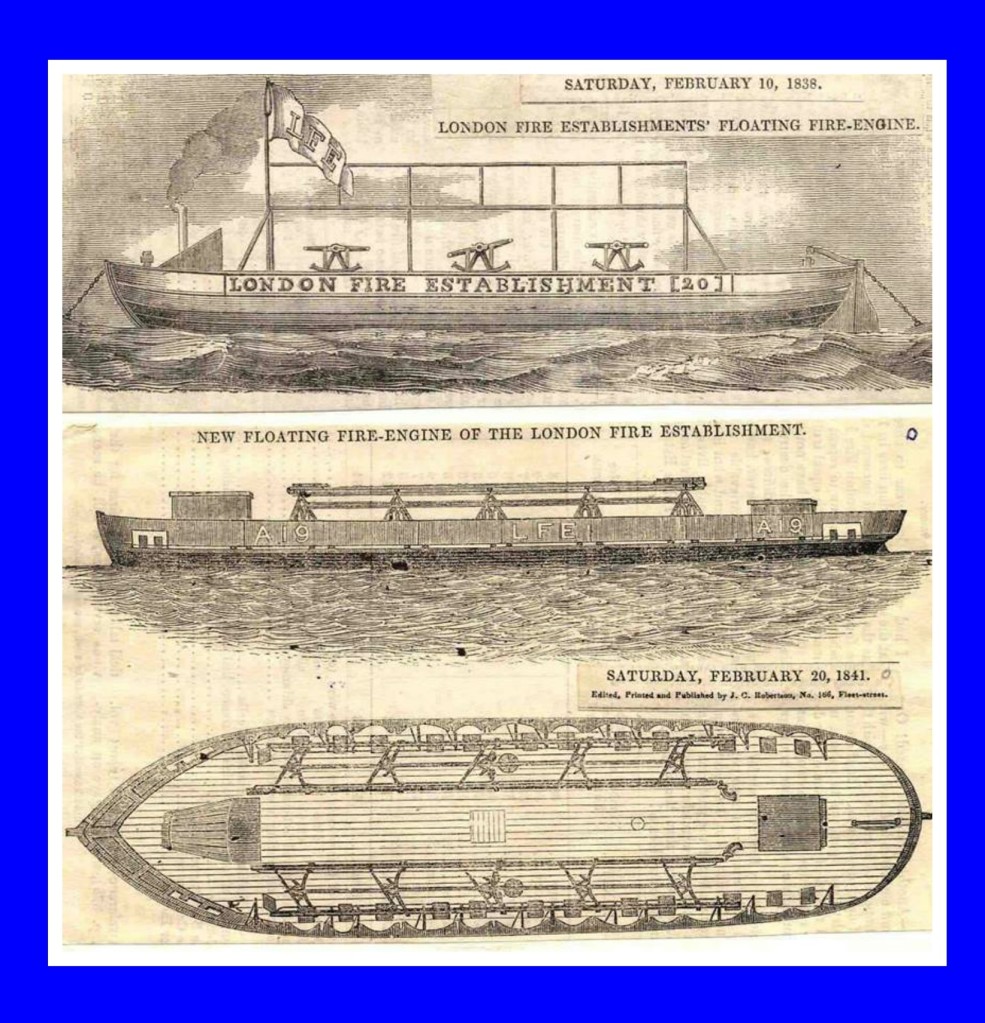

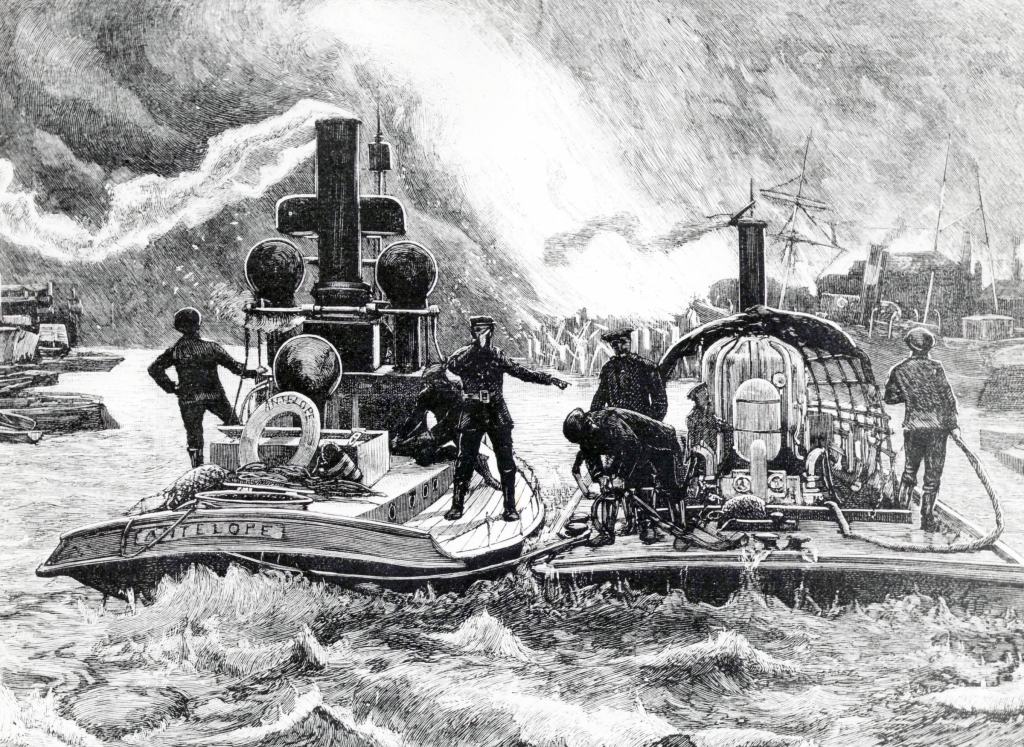

The brigade’s two fire floats were still the oar propelled craft with manual pumps. One, pumped by 90 men, was located by Southwark Bridge (Upper float), the other, pumped by 45 men, was stationed off King’s Stair in Rotherhithe (Lower float), on the south side of the Thames. The LFEE firemen were clothed in a matching uniform. They were recruited with reference to their “expertness and courage at fires”. A nominated number of the firemen were required to be ready at all hours of the day and night. Their engines available to depart at a minute’s notice in case of a fire. It was, as a rule, stipulated that when a fire occurred in any one district, all the men and engines of that district would attend to the address given, together with two-thirds of the men and engines from each of the two adjoining districts, with one-third from the one most removed from it. However this arrangement was modified according to the extent and size of a fire, or the number of fires which may be burning across London at one time.

Braidwood brought to London his new ideas and original techniques to his new Brigade. He encouraged the idea of getting into a building to fight a fire and not the insurance brigade’s previous practice of the ‘long shot’, a hose played at a distance from the outside of the building. He also insisted that no fireman should ever enter a building alone, and that there should always be a comrade to assist in case of an accident or if the colleague collapsed due to the heat or fumes.

Some writers have not been overly kind, or fair, to Braidwood commentating on his alleged delay in the introduction steam fire engines on fire floats. It was noted by some that despite the growth of the newly invented steam pumps Braidwood was a traditionalist when it came to maintaining the manual fire engines he used. For many years the introduction of steam pumps into the LFEE was delayed. In fact Braidwood was sympathetic to the purchase of a steam fire engine mounted on a float and submitted a favourable report seeking the Committee’s approval for its purchase. It was the Committee who rejected the proposal arguing, once again, that they considered it expensive and felt the steam pumps delivered greater pressure than the manuals, therefore the firemen’s jets would cause too much water damage and deter the firemen from getting close to the fires.

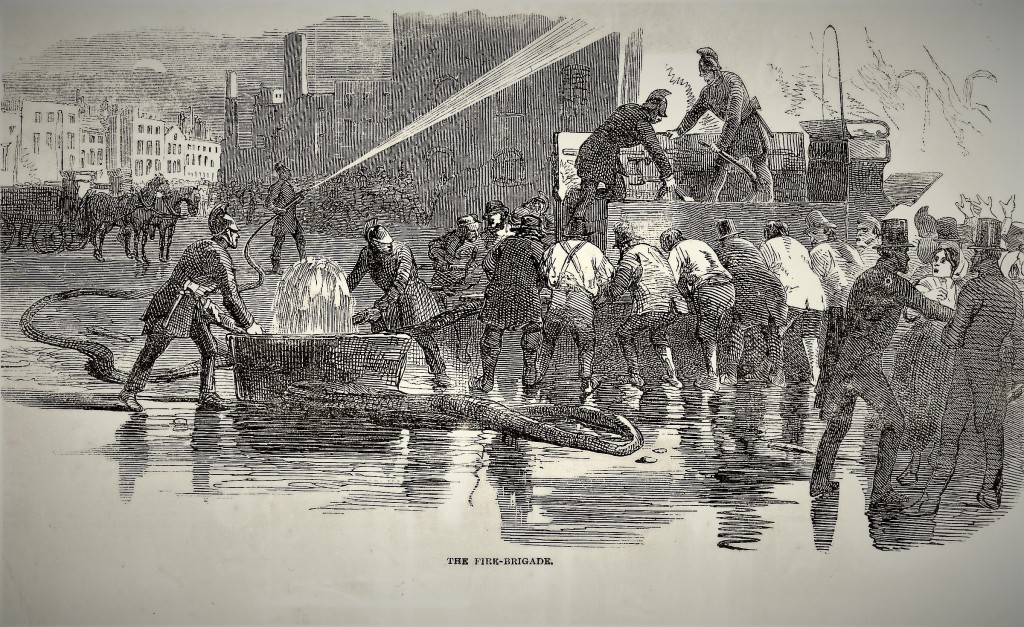

The manually operated fire engines of the early nineteenth century were themselves both heavy and cumbersome. They were also expensive to operate, with up to twenty men, ten on each side, to work the pump handles up and down. He did expand the float engines on the Thames. They were long, wide oar powered boats, many pumpers were required to operate the pumps the fire-floats carried. There was the additional problem of not only paying the pumpers but ferrying relays of pumpers from the shore to the floats. At a fire in Tooley Street in 1837 the LFEE manual fire-float had required three hundred and thirty-three pumpers to work the pumps during the course of the fire.

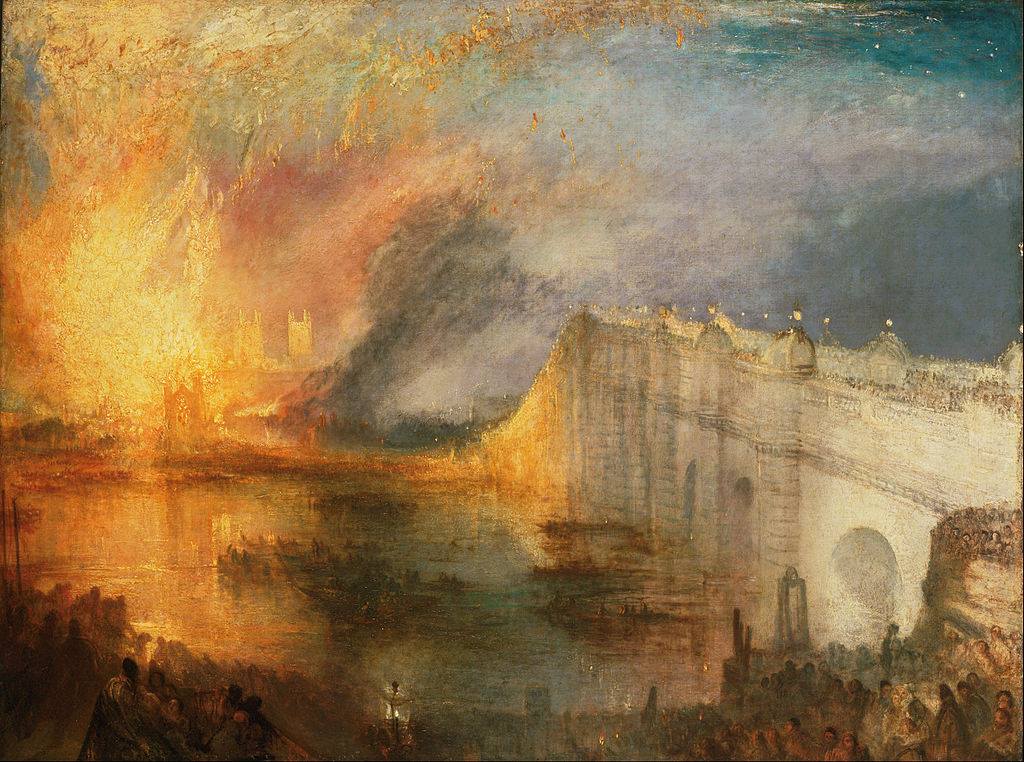

The first high profile test of the new London brigade came when the force was less than two years old. On Wednesday 16th October 1834 the Palaces of Westminster caught fire. By the late Georgian period, the buildings of the Palace of Westminster had become an accident waiting to happen. The rambling complex of medieval and early modern apartments making up the Houses was by then largely unfit for purpose. Complaints from MPs about the state of their accommodation had been rumbling on since the 1790s, and reached a peak when they found themselves packed into the hot, airless and cramped Commons chamber during the passage of the Great Reform bill.

Throughout the day, a chimney fire had smouldered under the floor of the House of Lords chamber, caused by the unsupervised and ill-advised burning of two large cartloads of wooden tally sticks (a form of medieval tax receipt created by the Exchequer). At a few minutes after six that evening, a doorkeeper’s wife returning from an errand finally spotted the flames licking the scarlet curtains in the Lords chamber where they were emerging through the floor from the collapsed furnace flues. There was panic within the Palace but initially no-one seems to have raised the alarm outside. A huge fireball exploded out of the building at around 6.30pm, lighting up the evening sky over London, and immediately attracting hundreds of thousands of people.

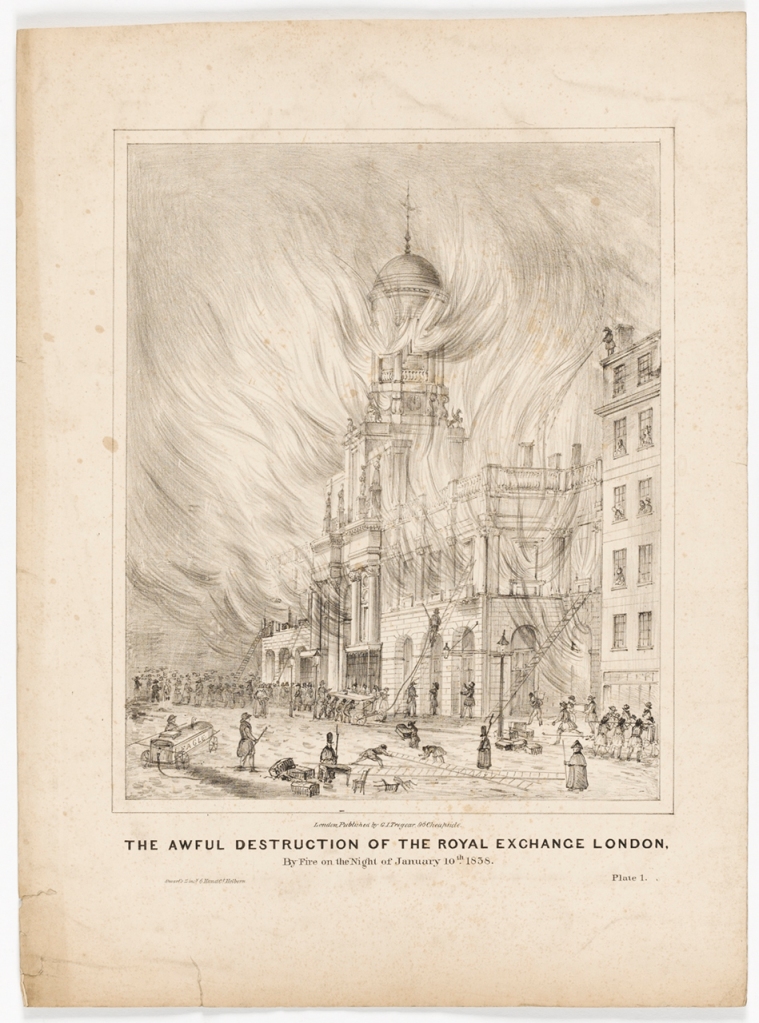

The damage to the wrecked and uninsured Palace was estimated at two million pounds. No-one, however was prosecuted, though the public inquiry which followed found various people guilty of negligence and foolishness. Braidwood was praised for his leadership and the standing of his LFEE force greatly improved. Yet despite the fire Braidwood still refused to consider steam fire engines. Plans for a floating steam fire engine were submitted by Braithwaite (the inventor of the land steam fire engine) in 1835. The plans were rejected.

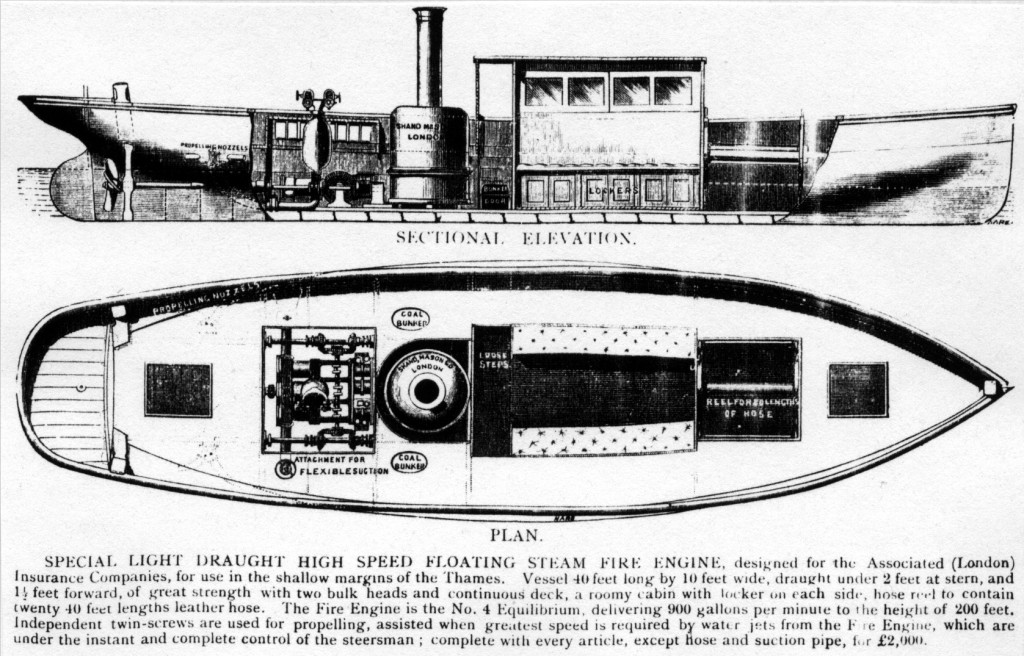

However, a large riverside fire occurred some months later and Braidwood had a mini revolt with the pumpers he had on-board one of the oar powered fire-floats. They demanded more beer, the payment for the pumpers, and stopped pumping several times. As a result Braidwood finally had a steam pump fitted to the float. Initially it was driven using the jets of water as its propulsion system but this did not prove successful. It was a tug that was used to tow the float to the fire. The savings made by not having to pay pumpers meant building a new steam fire-float a financially viable option. London finally had its first water-borne steam fire engine.

Throughout its tenure the LFEE remained a private body overseen by the insurance companies, although it was seen as the public fire service for the whole of the then London area. In an LFEE advert, published on 1st January 1833, it announced their goal was to provide better fire protection to the inhabitants of the ‘Metropolis’. James Braidwood led a force that consisted of 80 watermen (firemen) and operated from 19 fire stations.

Braidwood had instituted formal training programs for his firemen, and required that they have working knowledge of the district that they were appointed to. The LFEE was considered to be an efficient organisation. Braidwood a formidable leader of his men. However, the large insurance offices did not consider the protection the Brigade provided adequate for the City of London, and preferred fire protection to be publicly funded. London was rapidly expanding and so was the cost of protecting the Metropolis from fire.

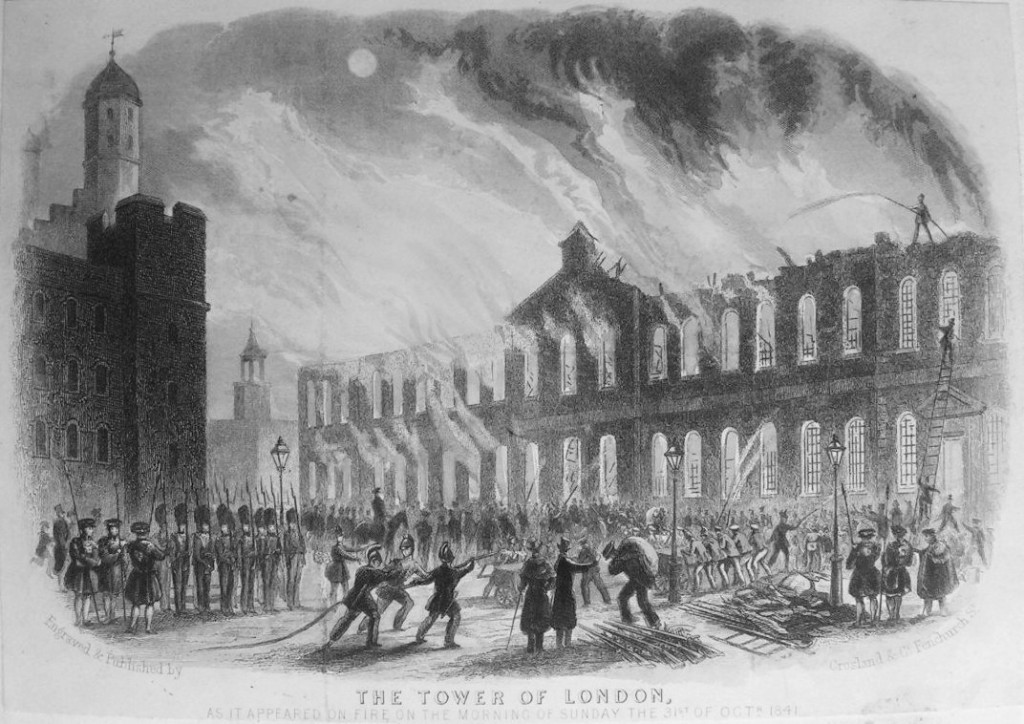

Today banner news headlines of sensational news stories is the norm. However, it is not such a recent innovation. Even back in 1841 this style of news reporting was being produced by both weekly journals and especially the daily newspapers. This is a flavour of the “Latest Particulars of the Awful Fire and Total Destruction of the Tower of London on the Night of Saturday 30th October 1841, “by J T Wood, printer and publisher of Fore Street, Cripplegate, London.

In Mr Wood’s view, this was “the most alarming and destructive fire that has occurred within the memory of the present age”. In the midst of the general confusion”, says Wood, “we could but remark on the absolute sublimity of an element let loose, roaming at discretion, from building to building the fire seemed to rejoice to madness, emitting light and heat which astonished…”

The fire was, in fact, first noticed at about half past ten on the evening of the 30th October 1841, by a sentinel on duty near the Jewel Office. He raised the alarm by firing his musket and the entire battalion of the Scots Fusilier Guards turned out. Flames soon burst out from windows of the Round Tower. Colonel Auckland Eden, the Officer Commanding, directed the troops to turn out the nine Tower manual engines. These were soon supplemented by the LFEE fire brigade engines. The Round Tower was rapidly consumed and the fire had spread to the Armoury roof. Braidwood’s firemen carried their hoses from two of the brigade engines into the Armoury and trained them on the ceiling and walls, but they had to leave hurriedly when the ceiling began to give way.

Efforts of the firemen and soldiers to put out the fire were hampered by the fact that the water tanks under the Tower contained very little water. Also, the Thames was at low tide, so that when eventually Braidwood’s floating engines arrived and moored off the Traitor’s Gate, his men had over 700 feet of hose to lay out and could do little but supply water to the fire engines nearer the fire.

Efforts of the firemen and soldiers to put out the fire were hampered by the fact that the water tanks under the Tower contained very little water. Also, the Thames was at low tide, so that when eventually Braidwood’s floating engines arrived and moored off the Traitor’s Gate, his men had over 700 feet of hose to lay out and could do little but supply water to the fire engines nearer the fire.

At about two o’clock, a rumour spread about that a large magazine was attached to the Armoury and some of the crowd dispersed hurriedly, fearing an explosion. This was apparently occasioned by the loud roaring of the flames, which went on until about 2.45am on the 31st October, when the fire began to abate and the firefighters were able to get nearer to the ruins.

By about four o’clock in the morning of the 31st October, the fire was out in most places although the ruins smouldered for days. There was one fatal casualty, a fireman who was killed by falling masonry. Almost everything was destroyed.

Immediate steps were taken by the Government to find the cause of the fire and to examine the conduct of officers and troops but there is no reason to think that the fire was other than accidental. Probably it was caused by the armourer’s forge in the Round Tower, or the flues of the stoves there.

At about two o’clock, a rumour spread about that a large magazine was attached to the Armoury and some of the crowd dispersed hurriedly, fearing an explosion. This was apparently occasioned by the loud roaring of the flames, which went on until about 2.45am on the 31st October, when the fire began to abate and the firefighters were able to get nearer to the ruins.

By about four o’clock in the morning of the 31st October, the fire was out in most places although the ruins smouldered for days. There was one fatal casualty, a fireman who was killed by falling masonry. Almost everything was destroyed.

Immediate steps were taken by the Government to find the cause of the fire and to examine the conduct of officers and troops but there is no reason to think that the fire was other than accidental. Probably it was caused by the armourer’s forge in the Round Tower, or the flues of the stoves there.

The Tooley Street fire would bring Braidwood’s reign to a tragic end. James Braidwood had proved himself to be a well-respected leader of his men. He was popular with the public too. He was a quiet man, in fact he was described as a gentle character with a devoted wife and family when he was not waging battle against many of the major fires to confront the City of London and area of the LFEE brigade. He was also loyal to his employers, the insurance companies. He kept his eye on the ball throughout his career in London, a frequent visitor to his fire stations, he also attended tests and trials of the new fire engines and fire equipment. However he was also a cautious man, taking time to consider these new developments before making changes to previous practices.

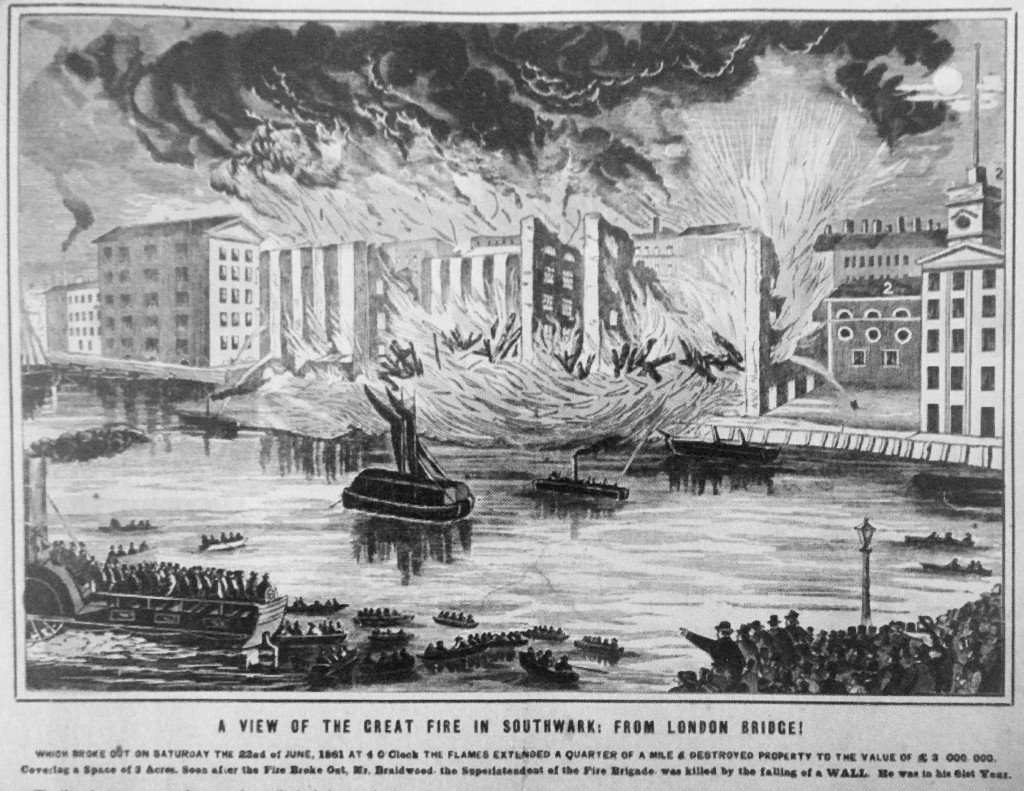

On the 22 June 1861 it may have well have been an average day for Braidwood. What he was engaged in prior to the outbreak of fire in Tooley Street remains a matter of conjecture, and is of little concern to what followed. It had been a hot summer day in London. Scovell’s warehouse was located on the river’s edge in Southwark, adjacent to London Bridge. The hot day may have been the reason some of the substantial iron, fire-proof, doors had been opened and allowed air to flow between the storage areas on various floors. What is known is that the doors should, in fact, have remained closed. The warehouse contained vast quantities of hemp, cotton, sacks of sugar, wooden casks of tallow, bales of jute, boxes of tea and spices.

Later reports would suggest the fire, like most fires, started small. Bales of damp cotton giving rise to very higher temperatures until the threshold arrived where spontaneous combustion occurred. As the flames rose and spread so the fire consumed ever more goods. With the iron doors not containing the blaze it soon spread beyond its point of origin.

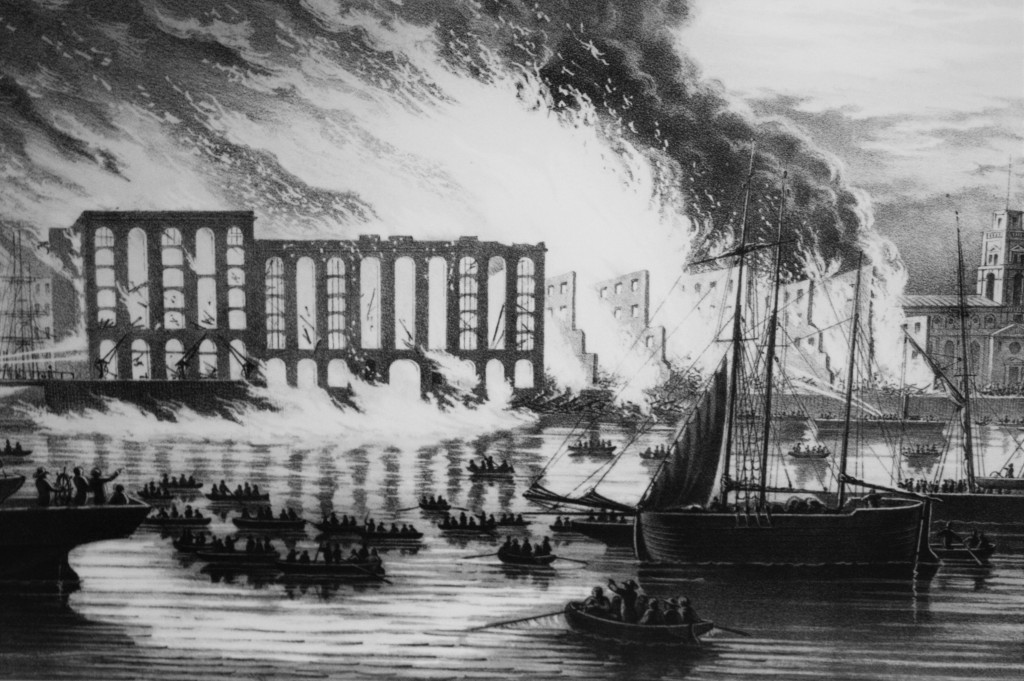

The alarm was finally raised around five o’clock in the afternoon. It became immediately apparent that the fire had a firm hold on Scovell’s wharf and was spreading to the adjoining Cotton’s wharf, and it would eventually consume both Hay’s and Chamberlain’s wharves too. Braidwood was quickly on the scene from Watling Street and had twenty-seven horse drawn engines, one steam engine, his two fire-floats and one hundred and seventeen firemen and officers, plus fifteen drivers fighting this conflagration on the south side of the River Thames. The fire had such a hold that water from the firemen’s hose evaporated before it even reach the boundary of the fire. Burning tallow, oil and paint flowed onto the river, almost consuming one of the fire-floats. The winds and thermals caused by the fire, aided by the Thames currents, sucked small boats into the flames.

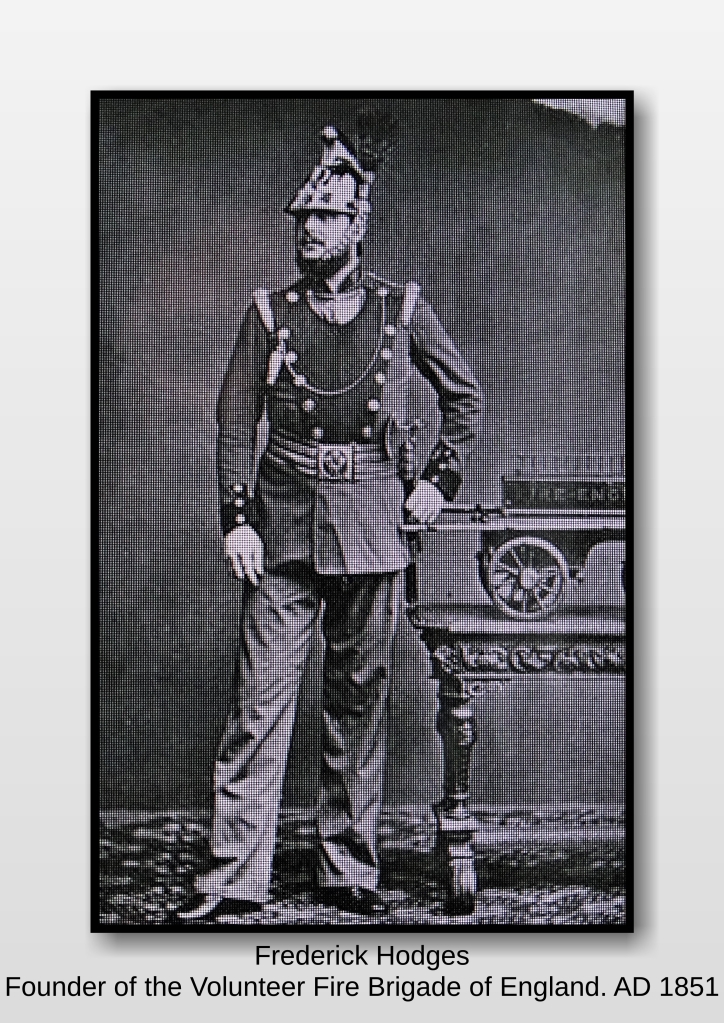

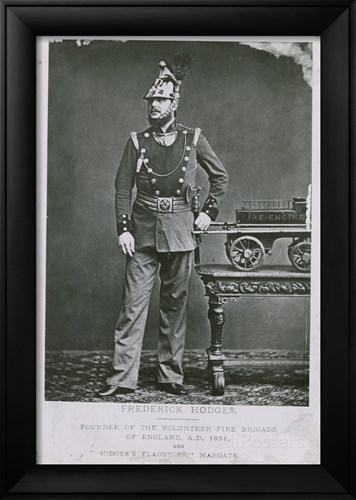

Braidwood was not fighting the flames unaided. Capt. Hodges had brought his private fire brigade to assist Braidwood in his endeavours, his two steamers working alongside the LFEE’s solitary steamer. Hodges’s firemen was joined by other private brigades before parish manual pumps were rushed to the Thames-side conflagration too. Sadly these parish pumps did little to help the situation, poor training and even poorer leadership of their crews only added to the confusion and nuisance their arrival caused.

It was seven in the evening when one of his men reported the fire-floats were scorching and was seeking Braidwood’s instructions. Braidwood made his way to the river bank by way of a narrow alley off Tooley Street to see what the situation was for himself. On the way he paused to give aid to one of his men who had gashed his hand. Braidwood removed his red silk Paisley neck silk to use as a bandage to bind the man’s bleeding hand. Moving on towards the river, and accompanied by Peter Scott, one of his officer’s, a warehouse wall many stories high suddenly bulged and cracked before giving way completely. It fell with a deafening noise, killing both Braidwood and the officer instantly. The efforts by his men to save the two were fruitless, but they tried anyway until beaten into a retreat by the relentless fire. Given the contents of the warehouses it is hardly surprising that explosions occurred, these projected flaming materials far and wide, setting fire to other warehouses and buildings. Braidwood’s death was said to have created confusion and disorganisation at the fire since there was no one appointed to lead in his absence.

The fire burned for another two days, totally out of control. Tides ebbed and flowed. On the high tides the fire-floats could move closer to the blaze but whatever progress they made was mitigated when the tide went back out and they had to move back towards mid-stream to direct their hoses. For over a quarter of a mile the south bank of the Thames was ablaze. Braidwood’s body, and that of his companion, lay under the hot brickwork for three days before they could be recovered. Whilst no other firemen perished in the fire it claimed the lives of four men on the river attempting to collect tallow.

James Braidwood was buried at Abney Park Cemetery on 29 June 1861. He was buried alongside his stepson, who was also a firefighter and had been killed in a fire five years prior. The funeral procession was a mile and a half long and shops were closed with crowds lining the route. As a mark of respect, every church in the city rang its bells. The buttons and epaulets from his tunic were removed and were distributed to the firefighters of the LFEE.

The death of Braidwood left the LFEE bereft of any natural successor from its own ranks. The insurance company had not appointed a deputy. It seemed that they had considered Braidwood immortal. They once again looked outside the capital for a suitable replacement. They found one in the guise of a certain Captain Eyre Massey Shaw, late of the North Cork Rifles. It was a commission that Shaw had resigned from the year before the Tooley Street fire, when in 1860 he was appointed Chief Constable of Belfast.

Shaw took the job. Born in 1830 he was thirty-one when he arrived at Watling Street, the LFEE headquarters station, to take charge of the Brigade in the latter part of 1861. Shaw had had a mixed background. He was the son of a General. With a view to entering the Church he had studied at Trinity College, Dublin only then to enter the army. He was a man who loved the water and was considered to be a competent sailor. Donning the mantle of the LFEE’s new Superintendent he inherited the eighteen land stations of the LFEE and its two fire-floats. His brigade covered the ten square miles of central London and the City of London, an area that formed the greatest risk for the insurance companies. A useful indicator of the workload of the fire brigade is provided by Shaw himself in his annual report for 1861.

Fires in 1861. Totally destroyed 53. Considerably damaged 332. Slightly damaged 798. Total 1381

Two to six miles from nearest station 20.

Hazardous trades 25.

Number of buildings destroyed 113.

At great fire, e.g. Tooley Street. 33.

Fires at private houses 196

Totally destroyed 2

Considerably damaged 25

Slightly damaged 169

Fires at lodgings 115

Slightly damaged 105

Fires at churches 5

Fires at hospitals 1

Fires at places of entertainment 2

Fires at unoccupied premises 11

Slightly damaged 9

False alarms 19

Chimney alarms 137

The Fire Brigade, with 120 its skilled ‘workmen’, 36 engines, 18 stations and 2 floating engines is maintained at an expense of close upon £25,000 a year by the various fire-insurance offices who contribute in a rateable proportion on their business. The management is vested in a committee, which contains one representative from each office. (Cruchley’s London in 1865: A Handbook for Strangers.)

The insurance companies finally sent a note to the Home Office in 1864, giving notice that they had decided to discontinue with the LFEE. The writing was on the wall for the LFEE, the question for the Home Secretary was what to do next. He had already charged Capt. Shaw, via the insurance companies controlling board, to come forward with ideas.

Finally, after a very long time, with several schemes submitted by Shaw, the Government passed into law the Metropolitan Fire Brigade’s Act in 1865. At the end of its last year, prior to being taken over by the MBW in 1865, the LFEE had at its seventeen stations and one-hundred and thirty-one black-clad firemen, with two floating steam pumps, two large horse-drawn steam pumps, six small horse-drawn steam pumps and thirty-three small horse-drawn manual pumps. The Metropolitan Fire Brigade (MFB) came into being on the 1st January 1865. Its first Chief Officer was Capt. Shaw.