Britain’s first properly organised municipal fire brigade was that of Edinburgh formed in 1824. Chosen to lead this brigade was a 23-year-old surveyor named James Braidwood. He had under him eighty firemen, all part-timers, who were chosen from trades associated with methods of building construction such as masons, slaters, plumbers, etc, as it was felt that the knowledge of men working in these trades would help them in their new job. Braidwood trained and drilled his brigade until they became the most proficient in Britain. He encouraged his men to attack the fire at its source rather than just pour water into a building which was alight and to creep in low to gain the benefit of the layer of relatively fresh air drawn in from outside by convection from the blaze.

In 1833 the leading London insurance fire brigades decided to amalgamate into a combined unit and it was agreed that Braidwood should be thebest person to head this new establishment. His salary was £250.00 per annum, a respectable sum in those days.

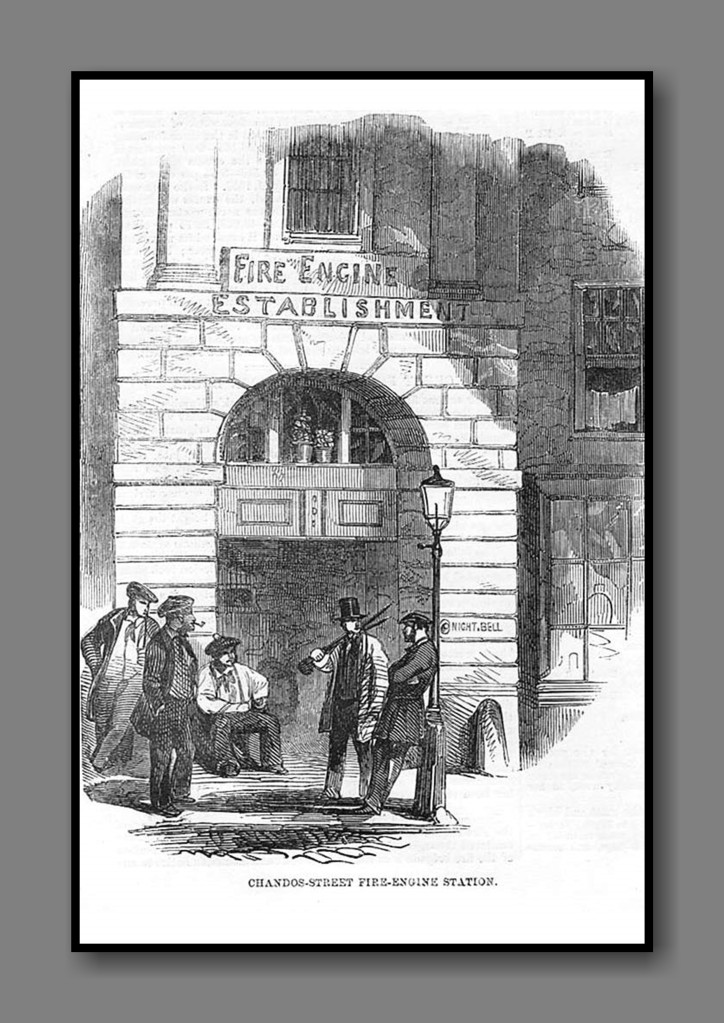

The London Fire Engine Establishment (LFEE), as this force was called, comprised the brigades of the Alliance, Atlas, Globe, Imperial, London Protector, Royal Exchange, Sun, Union and Westminster insurance companies. The LFEE had eighty full time firemen and nineteen fire stations. The men’s conditions were severe. Two men were always on a 24 hour watch while the remainder had to be within the station building in readiness for call-out at any time. Each man was officially on duty 168 hours a week, leaving just four hours of spare time. The pay of £1.0s.0d per week was good and Braidwood had no difficulty in finding recruits, mainly from men used to working long hours for little pay on the Thames and waterways.

The growth of London was too much for the insurance firemen to deal with and the City of London demanded a new force after a series of disastrous (expensive) large fires that found their firefighting skills seriously wanting. With just his whole-time ‘professional’ LFEE firemen, Braidwood started structured fire training, established a duty system and brought new ideas and original techniques into fire-fighting. Getting ‘stuck in’ would be the hallmark of future generations of firemen who followed these early practitioners of their craft. His men were trained in the dark, and made to get near the source of a fire, crawling low on their hands and knees, and below the rising hot gases. He also insisted that no fireman enter a building alone, stating that there should also be a ‘buddy’ or comrade to assist in the case of an accident or if a man collapsed in the heat or fumes.

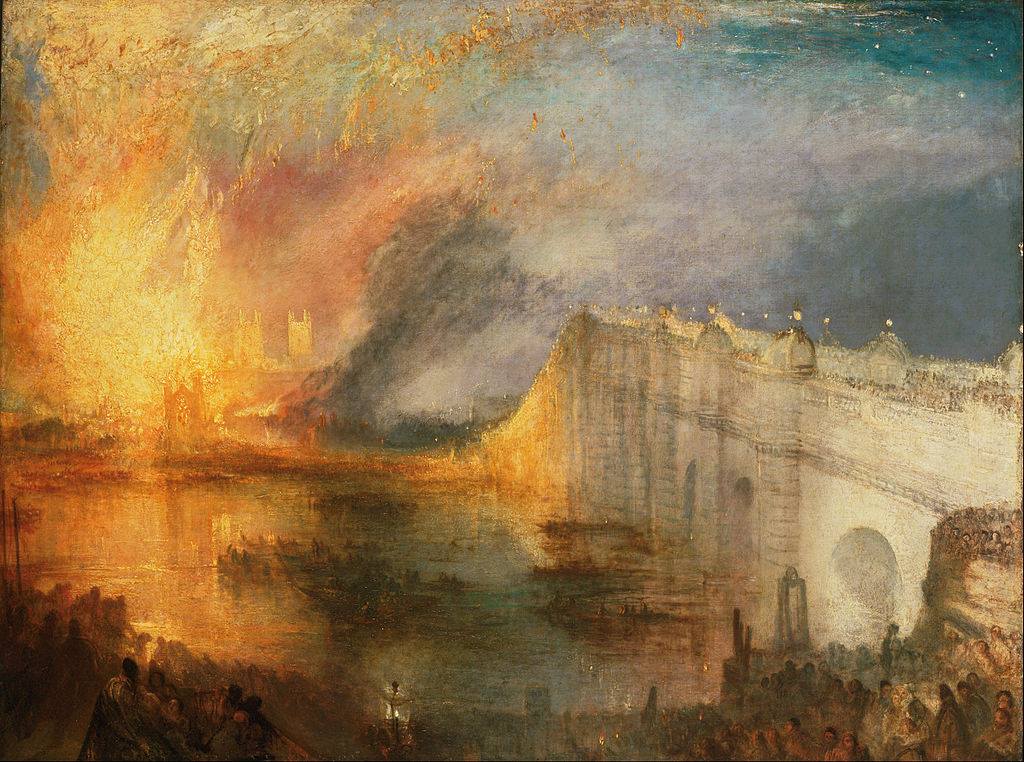

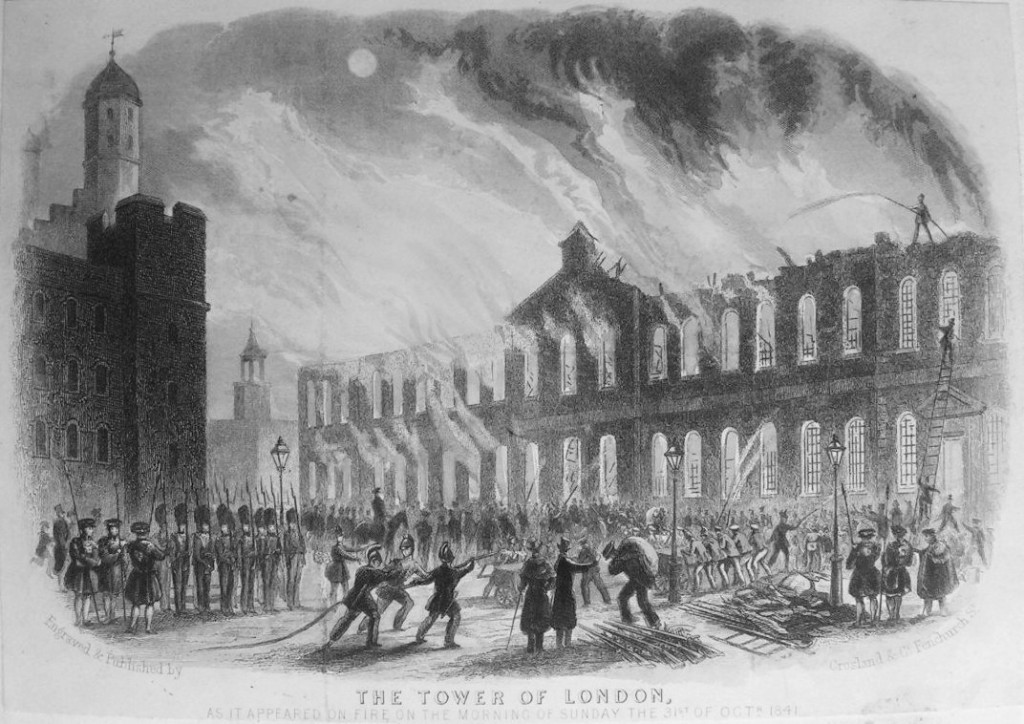

In October 1834 Braidwood’s LFEE attended a fire at the Houses of Parliament and despite the efforts of sixty-four men and twelve engines only Westminster Hall was saved. The buildings were not insured and the proprietors of the London Fire Engine Establishment petitioned the government to set up a proper organised firefighting force. The government, sensing considerable expenditure, declined, leaving the fire protection of central London in the hands of the insurance companies. They did, however, agree to the provision of buckets, hand pumps and a few fire engines for use at important places, but when the Tower of London Armoury was destroyed by fire in October 1841 the firefighting equipment there was found to be in a sorry state.

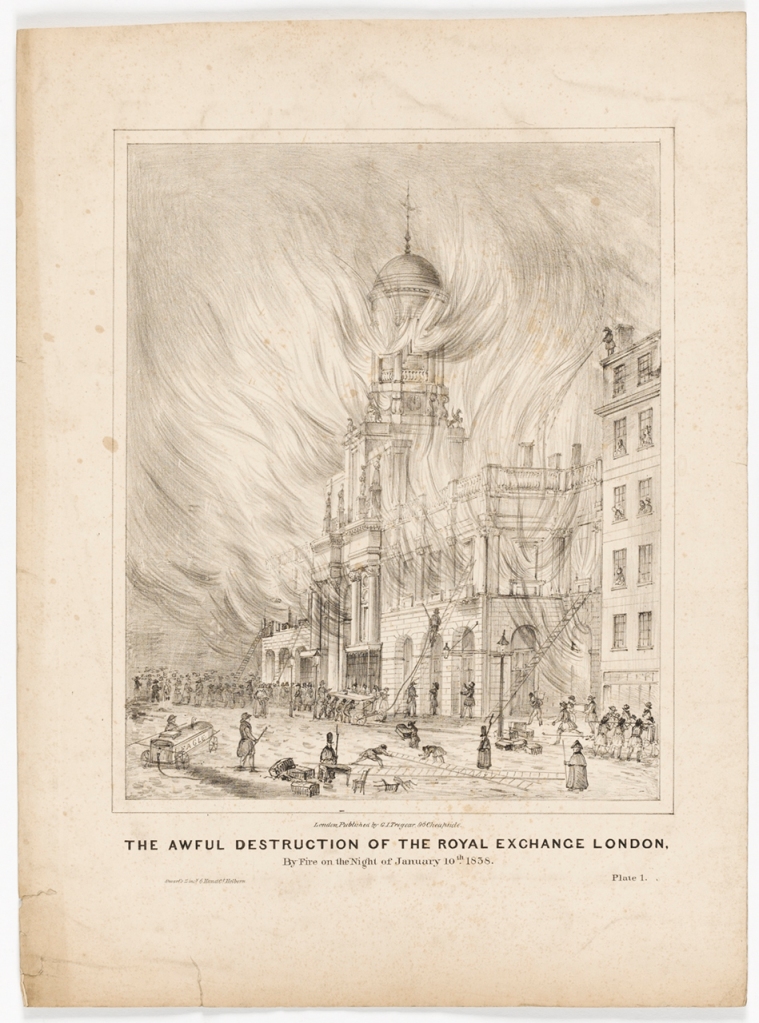

Occasionally the Insurance Companies’ brigade was powerless to act, even though their equipment was kept in first class order. One such incident occurred in a particularly cold January night in 1838 when the Royal Exchange caught fire. The wooden fire plugs in the street mains were frozen solid and when alternative water supplies were found the fire engine froze solid too.

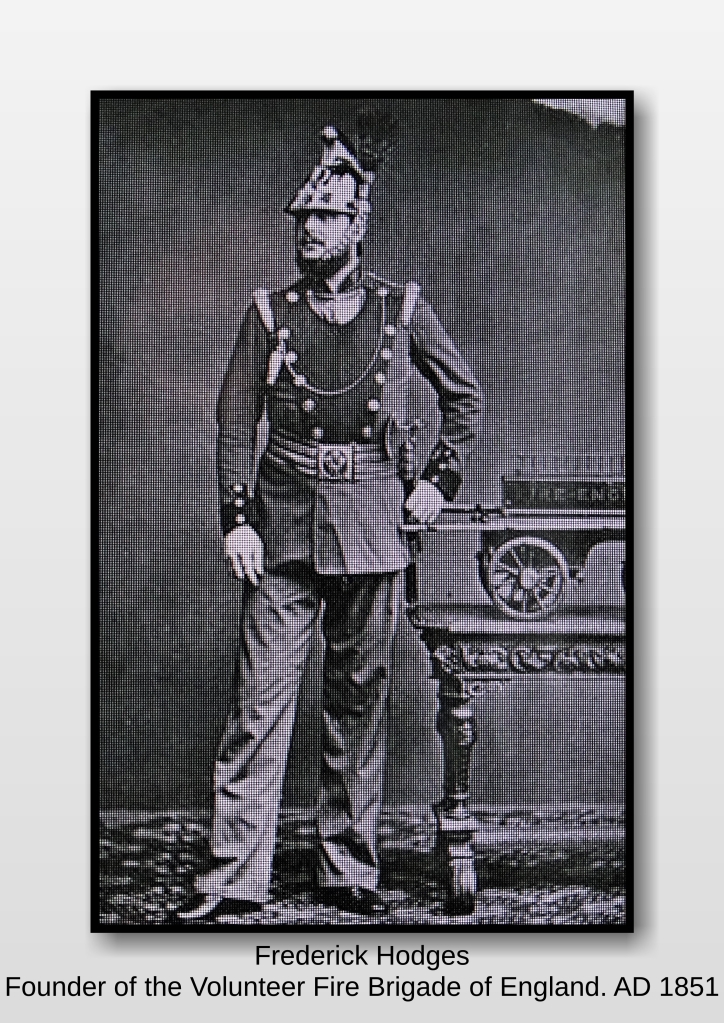

Some private concerns formed their own fire brigades and often fought side by side with the LFEE. One such brigade was that of Frederick Hodges, who owned a distillery at Lambeth. Hodges claimed that his brigade, in relation to its size, was better equipped than Braidwood’s, and thanks to a specially built 120 foot high look-out mast, his brigade could often reach the scene of the fire before the LFEE, who then missed the reward paid to the first engine to the scene of a blaze.

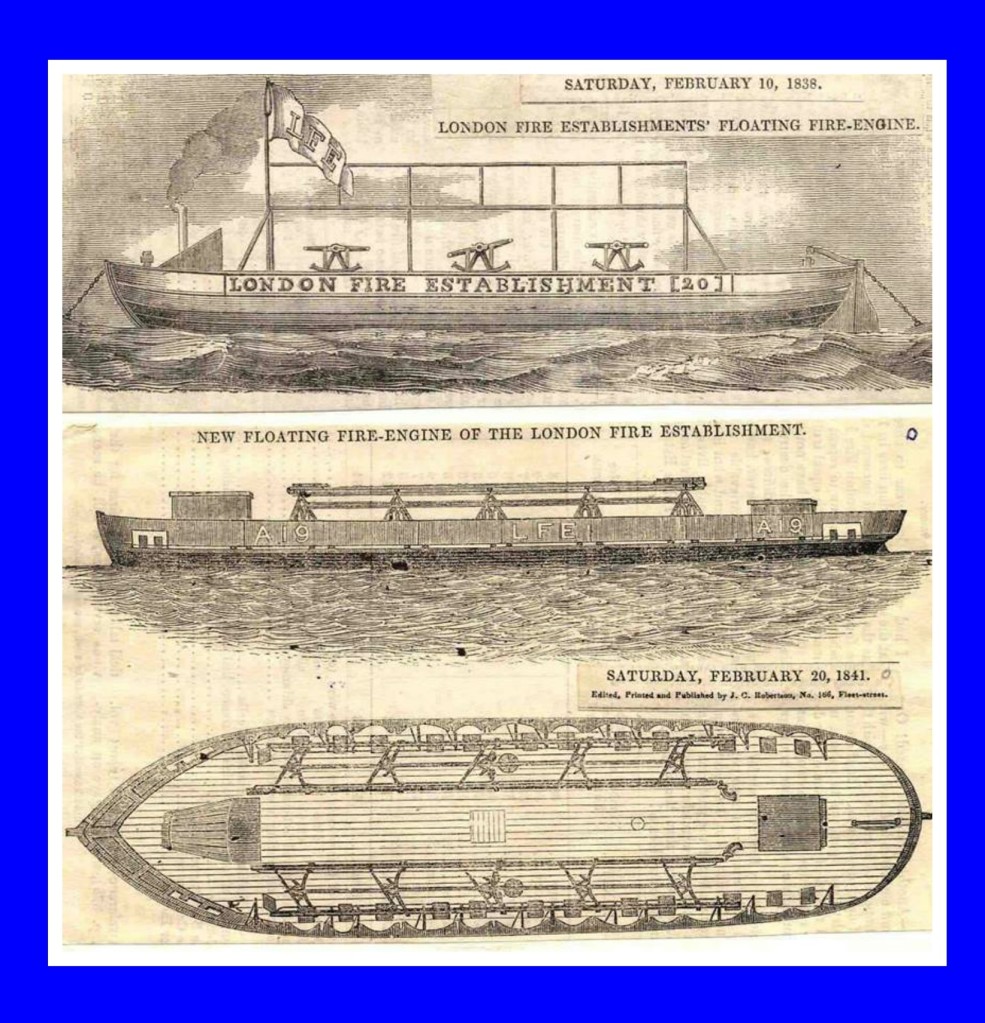

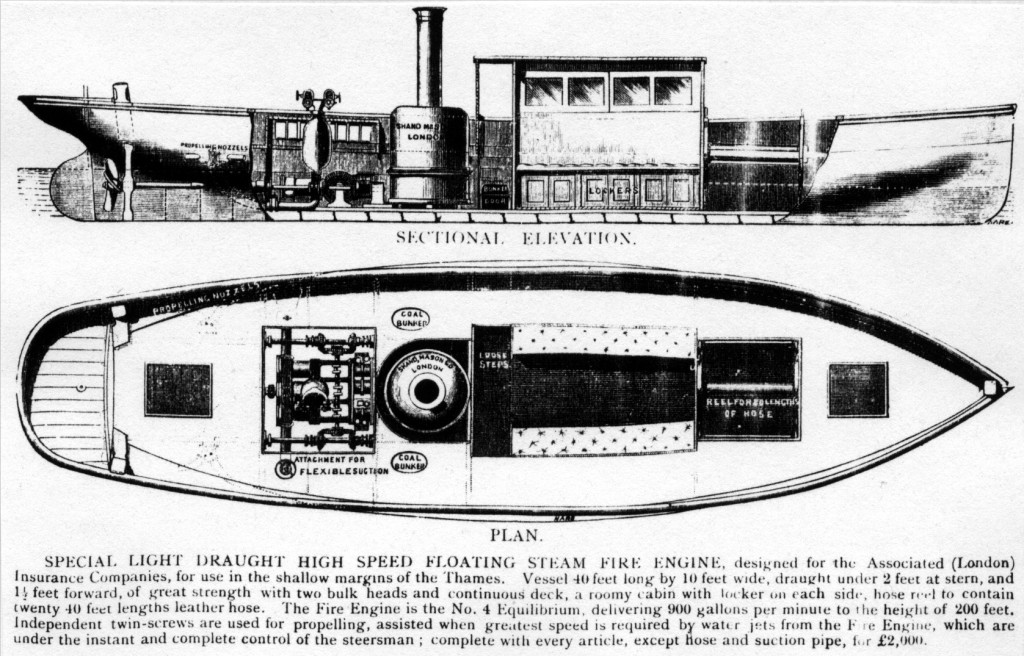

Though he was always seeking ways to improve the efficiency of the brigade, Braidwood was basically opposed to steam fire engines as he felt the powerful jet with this type of engine would encourage his men to revert to the old ‘long-shot’ method of firefighting instead of tackling the fire at its heart. He did, however, introduce a floating steam fire engine to deal with waterfront fires and a Shand horse drawn steamer was being experimented with in 1861.

Braidwood’s demise.

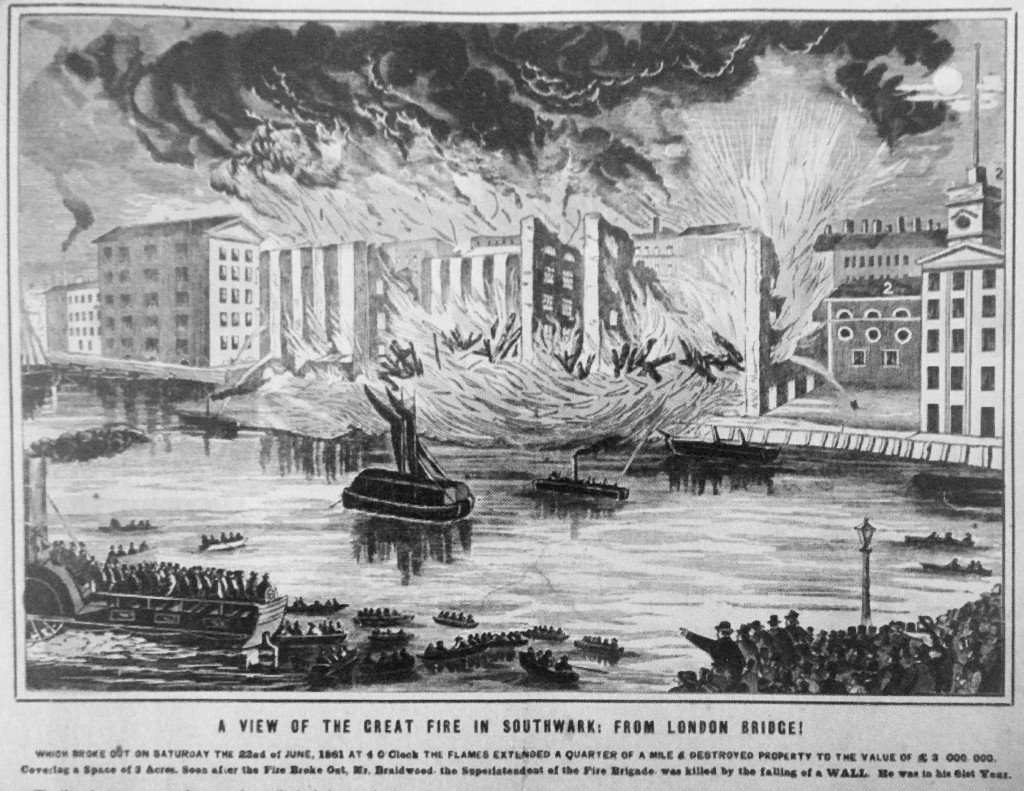

The 22 June 1861 it may have well have started as an average day for James Braidwood, Superintendent in charge of the London Fire Engine Establishment. What he was engaged in prior to the outbreak of a fire in Tooley Street is a matter of conjecture. it remains of little concern given what followed. It had been a hot summer London day. Scovell’s was a large general warehouse located on the river’s edge in Southwark, adjacent to London Bridge. The hot day may have been the reason some of the substantial iron, fire-proof, doors being opened and to allow air to flow between the storage areas on the various floors. What is known is that these doors should, in fact, have remained closed. The extensive warehouse contained vast quantities of hemp, cotton, sacks of sugar, wooden casks of tallow, bales of jute, boxes of tea and spices.

Later reports would suggest the fire, like most fires, started small. It was believed that bales of damp cotton gave rise to very higher temperatures reached the threshold where spontaneous combustion occurred. As the flames rose, and spread, the fire consumed ever more goods. With the open iron doors not containing the blaze it soon spread beyond its point of origin.

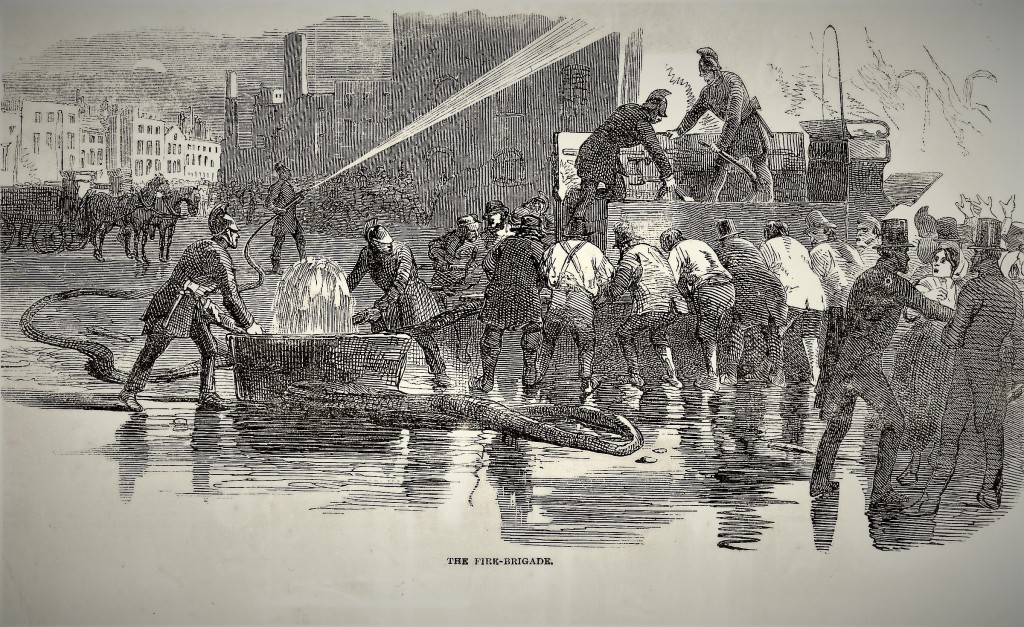

The alarm was finally raised around five o’clock in the afternoon. It became immediately apparent that the fire had a firm hold on Scovell’s wharf and was spreading to the adjoining Cotton’s wharf. It would eventually consume both the Hay’s and Chamberlain’s wharves too. Braidwood was quickly on the scene, from Watling Street LFEE headquarters and station, and he had twenty-seven horse drawn engines, one steam engine, his two fire-floats and one hundred and seventeen firemen and officers, plus fifteen drivers fighting this conflagration on the south side of the Thames. The fire had such a hold that water from the firemen’s hoses evaporated before it even reach the boundary of the fire. Burning tallow, oil and paint flowed onto the river, almost consuming one of the fire-floats. The winds and thermals caused by the fire, aided by the Thames currents, sucked small boats into the flames.

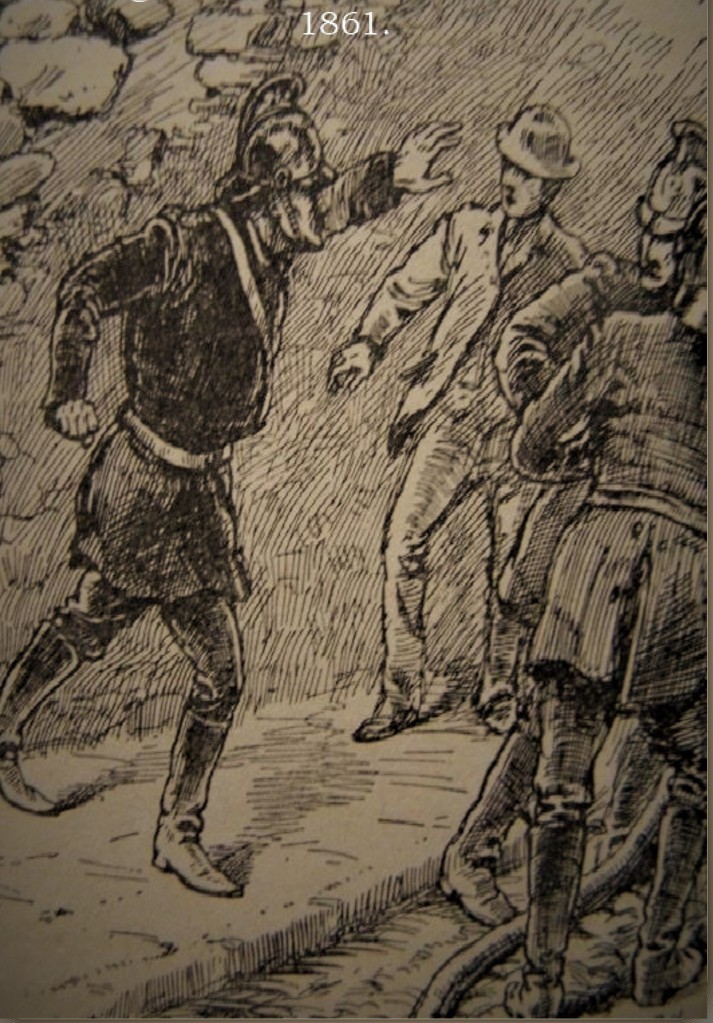

Braidwood was not fighting the flames unaided. Capt. Hodges had brought his private fire brigade to assist Braidwood in his endeavours, his two steamers worked alongside the LFEE’s solitary steamer. Hodges’s firemen were joined by other private brigades before London parish manual pumps were rushed to the Thames-side conflagration. Sadly these parish pumps did little to help the situation, in fact, poor training and even poorer leadership of their crews only added to the confusion and nuisance their arrival caused

the Tooley Street fire.

Captain Frederick Hodges owned a gin distillery in Lambeth. He also owned, and led, one of London’s most famous private fire brigades stationed at his south London distillery from the early 1850s. His was the first fire brigade to use an engine with steam as opposed to manual pump power. He had started his brigade on the 1st May 1851. It was common practice that the larger factories had a private fire brigade (in later times called ‘works fire brigades’). Hodges neighbours, Burdett’s Distillery and the Price’s Candle factory being two such examples. He later equipped his brigade with ‘two powerful engines’ supplied by Shand and Mason, in nearby Blackfriars, in 1854.

Things were not going Braidwood’s way. It would, tragically, get worse. Even the River Thames was working against him. The ebbing tide meant his fire-floats were kept a considerable distance from the all engulfing blaze due to the exposed foreshore and its mud flats. The firemen and the pilots of his fire-floats nevertheless still had their hands and faces blistered and burned by the enormous quantities of radiated heat as they directed their jets from their vantage points. Braidwood was considered to be at his calmest at times of greatest danger. He also cared greatly about his fireman.

It was seven in the evening when one of his men reported the fire-floats were scorching and was seeking Braidwood’s instructions. Braidwood made his way to the riverbank, by way of a narrow alley off Tooley Street, to see what the situation was for himself. On the way he paused to give aid to one of his firemen who had gashed his hand. Braidwood removed his red silk Paisley neck-silk to use as a bandage to bind the man’s bleeding hand. Moving on towards the river, and accompanied by Peter Scott, one of his officer’s, a warehouse wall many stories high suddenly bulged and cracked before giving way completely. It fell with a deafening crash killing both Braidwood and the officer instantly. The strenious efforts of his men to save the two were fruitless, but they tried anyway until beaten into a retreat by the relentless fire.

Given the contents of the warehouses it is hardly surprising that the subsequent explosions occurred. They projected flaming materials far and wide, setting fire to other warehouses and buildings. Braidwood’s death was said to have created confusion and disorganisation at the fire since there was no one appointed to lead in his absence.

The fire burned, totally out of control, for another two days. Tides ebbed and flowed. On the high tides the fire-floats could move closer to the blaze but whatever progress they made was mitigated when the tide went back out and they had to move back towards mid-stream to direct their hoses.

For over a quarter of a mile the south bank of the Thames was ablaze. Braidwood’s body, and that of his companion, lay under the hot brickwork for three days before they could be recovered. Whilst no other firemen perished in the fire it claimed the lives of four men on the river attempting to collect tallow. Their craft was surrounded by a river of flames flowing from the fire. Paints, oils, waxes and the very tallow they were trying to collect having ignited and streamed out onto the water’s surface, their boat was engulfed and the men died in the flames.

James Braidwood’s body was buried at Abney Park Cemetery on 29 June 1861. He was buried alongside his stepson, who was also a fireman and had been killed in a fire five years prior. The funeral procession was a mile and a half long and shops were closed with extensive crowds lining the route. As a mark of respect, every church in the city rang its bells. The buttons and epaulets from his tunic were removed and were distributed to the firemen of the LFEE.

The death of Braidwood left the LFEE bereft of any natural successor from its own ranks. The Insurance Companies had not appointed a deputy. It seemed that they had considered Braidwood immortal. They once again looked outside the capital for a suitable replacement. They found one in the guise of a certain Captain Eyre Massey Shaw, late of the North Cork Rifles. It was a commission that Shaw had resigned from the year before the Tooley Street fire, when in 1860 he was appointed Chief Constable of Belfast. His job description also covered that of Superintendent of the Belfast fire brigade, which Shaw discovered to be in a very unsatisfactory state of affairs. He immediately set about putting the brigade, and its firemen, on a more organised and professional footing. His success coming to the attention of the various London Insurance Companies, now urgently seeking a new Superintendent to lead the LFEE.

The Tooley Street fire cost the insurance companies dearly. The loss of property alone was estimated to be in the region of £1,500,000.00 to £2,000,000.00. To pay the pumpers they paid out a further £1,100.00. Rumours spread around the City of London that the companies would collapse, but they settled the claims and continued, albeit unhappily. The Tooley Street fire finally convinced the authorities that something ‘definite and decisive’ had to be done. It would take almost four years of negotiations between the Government, the Metropolitan Board of Works and the insurance companies before anything was done and London’s first municipal fire brigade was created; the Metropolitan Fire Brigade and led by Braidwood’s successor Capt. Shaw.

London’s first fire chief was given a hero’s funeral, one befitting the high regard that he had secured in London’s population. His funeral cortège was one and a half miles long, and all the church bells in the City of London tolled a farewell to this brave fireman.

The London Fire Engine Establishment 1865.