The London blitz begin in London 84 years ago this September. It was almost exactly twelve months after Britain had declared war on Germany. London was bombed for 57 consecutive nights.

That first major raid took place over the 7 September 1940. It was followed by aerial bombardments, usually under cover of darkness, over the Capital and many of Britain’s major towns and cities. (It is estimated that over an eight month period, around two million homes were destroyed and between 40,000 and 43,000 civilians lost their lives, with many more injured in addition to those killed and injured fighting the fires and conflagrations resulting from the bombing raids.)

Yet despite these chilling statistics, the Blitz served to strengthen rather than weaken British resolve, invoking what we now remember as the famous ‘Blitz spirit’. Yet only two months before those serving the in the London Fire Brigade, and in particular those who had joined the newly created Auxiliary Fire Service (AFS), where often vilified in the press and, on occasion, by the general public as war dodgers!

The Prime Minister of the time, Winston Churchill, would later coin the phrase, “Heroes with grimy faces“, referring to all regular firemen and the AFS firefighters. It was a fact that St Paul’s Cathedral would not be here today were it not for them.

The Blitz started on a Saturday, Saturday late afternoon to be precise. To some it might have seemed that WWII had finally arrived at their doorstep, although there had been other German air-raids before that fateful day. For some unfortunate ones it was the last day of their lives. Whilst for members of the enlarged London Fire Brigade and the other Brigade’s in the London Region it was to be the start of their ordeal by fire. The bombs would rain down for 57 continuous nights before individual, but still devastating, mass bombing raids would continue until May 1941.

For those 57 continious nights, and then frequent raids beyond, London’s firemen and women worked in very demanding conditions. They worked throughout the raids, even while the bombs were falling. The firefighters were at risk from collapsing buildings and falling shrapnel from anti-aircraft guns, often working15 hours at a time, in clothes that were soaked through.

The Auxiliary Fire Service

The likelihood of a Second World War was already being planned for in the early 1930s. Although not widely publicised the then National Government, under the premiership of Ramsey MacDonald, were considering what arrangements would be necessary to cope with enemy aerial attacks on its strategic population centres. This was just one of many problems for the Government, not the least of which was the vast economic trouble the whole country faced in the wake of the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and the subsequent widespread depression it caused.

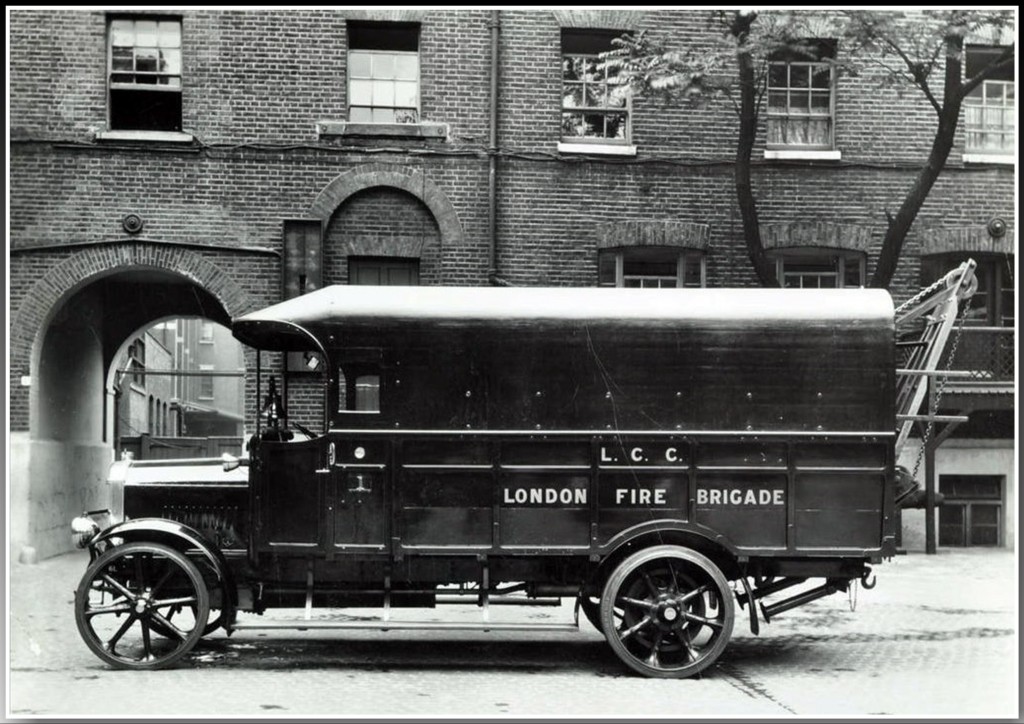

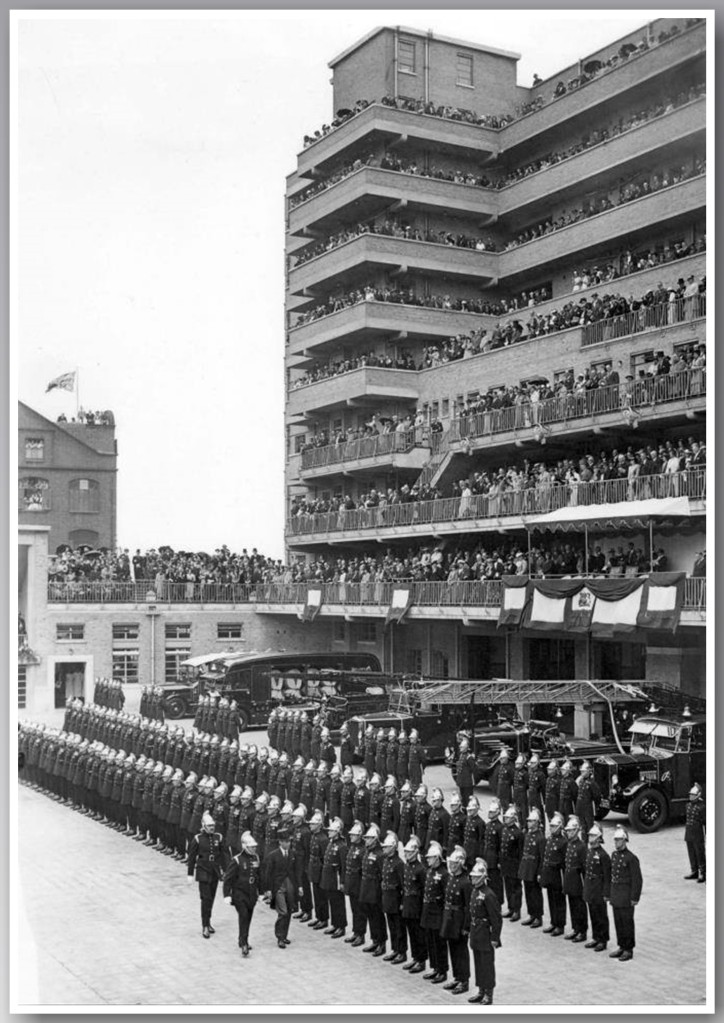

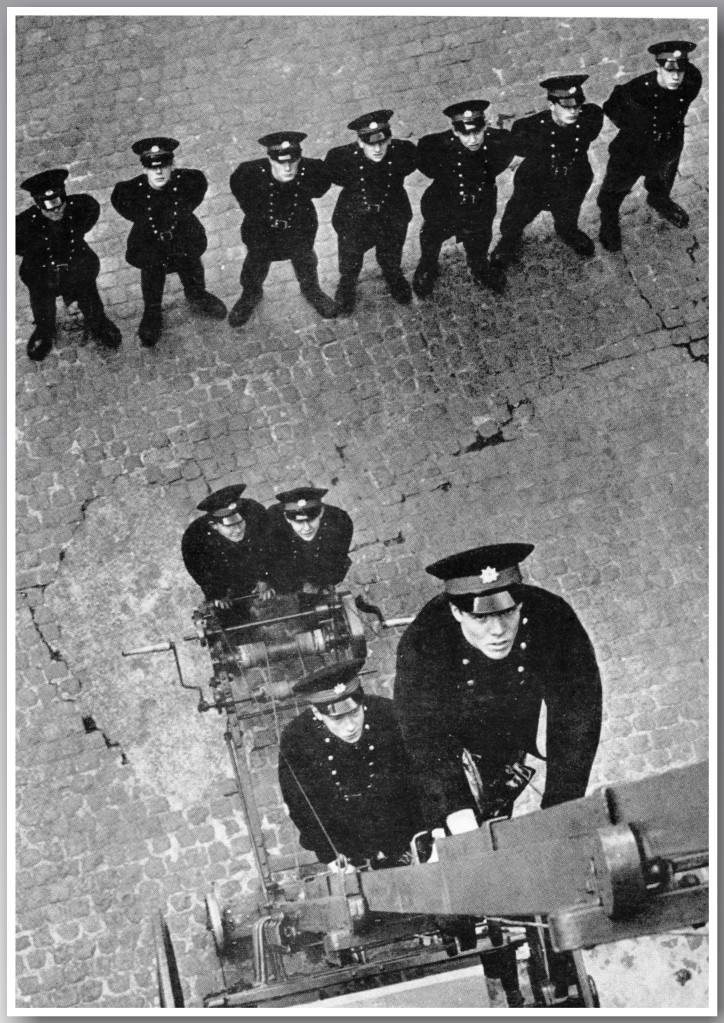

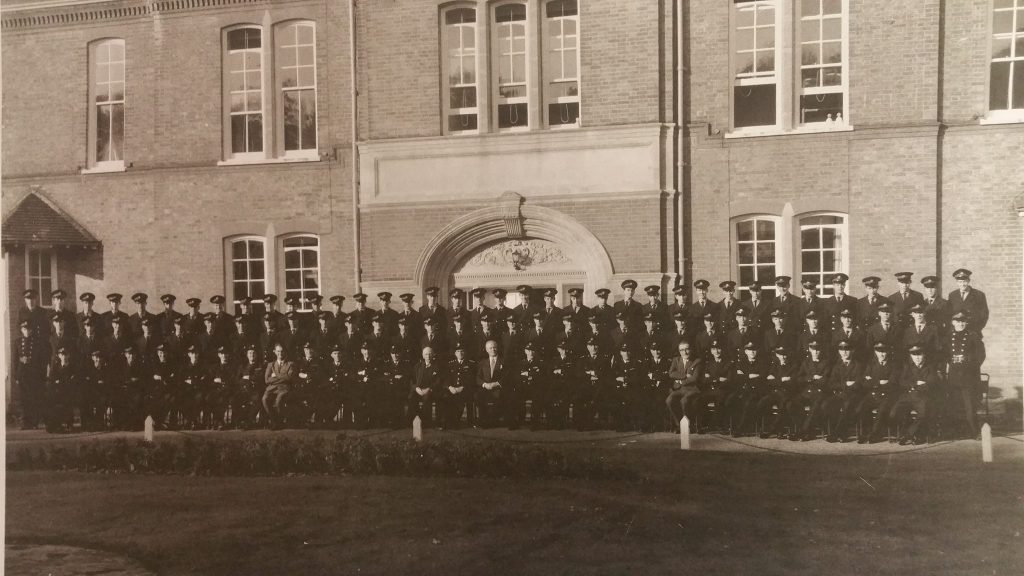

(Photo credit-London Fire Brigade.)

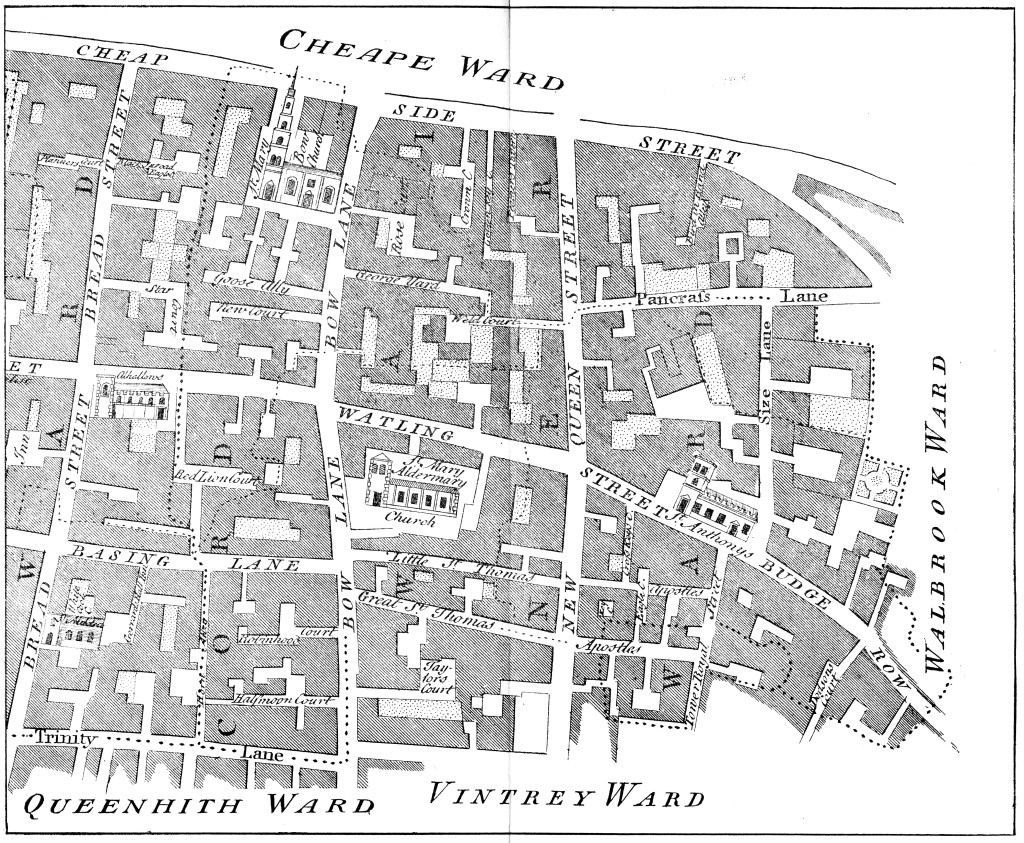

However, despite this background, the Home Office (then responsible for the Fire Service) held a series of seminars and secret planning meetings to deliver a strategy in the event of war and subsequent fire attacks on the British mainland from the air. London was considered a particularly vulnerable target from enemy action, not least because it was the nation’s seat of government and the City of London was crucial to the country’s financial and business interests. The London of the 1930s took on a vastly different look to the London of today. The River Thames provided easy access for shipping to the vast network of extensive docks and associated warehouses. The dockland warehouses, from Southwark and Blackfriars on the south bank and Tower Hill on the north bank, ran eastward to the Essex and Kent borders.

It was recognised at an early stage that it would require a massive expansion of the existing fire brigade(s) to deal with fires involving London’s central maze of narrow streets, warehouses filled with combustible products such as oils and grains and dockyards with acres of stacked imported timber. Failure to respond to such a challenge could leave London little more than a smoking ruin. However, before that day arrived the Auxiliary Fire Service (AFS) was formed and from March 1938 their numbers grew. Attracting the 28,000 proposed volunteers was a major logistical exercise. A massive recruitment drive was launched. Whilst sixty fire brigade vehicles toured London’s streets, a poster campaign was mounted and planes flew the over capital trailing recruitment banners. Even the Thames was used to advertise this new fire force and the Brigade’s high speed fireboat flew similar banners seeking recruits to supplement the London Fire Brigade’s river service.

The area we now know as Greater London had, prior to the outbreak of war, at least 66 fire brigades. This included the London Fire Brigade, the largest, which covered the whole of the former London County Council administrative area. Some of these other brigades were one fire engine outfits that only protected a small borough area while others had four or five stations such as West Ham and Croydon. Buildings and vehicles were seconded into service to house and equip this basically trained corps of AFS firemen and women that had now greatly expanded London’s fire service. Meanwhile garages, filling stations and schools, empty since the mass evacuation of children, were taken over and adapted as fire stations.

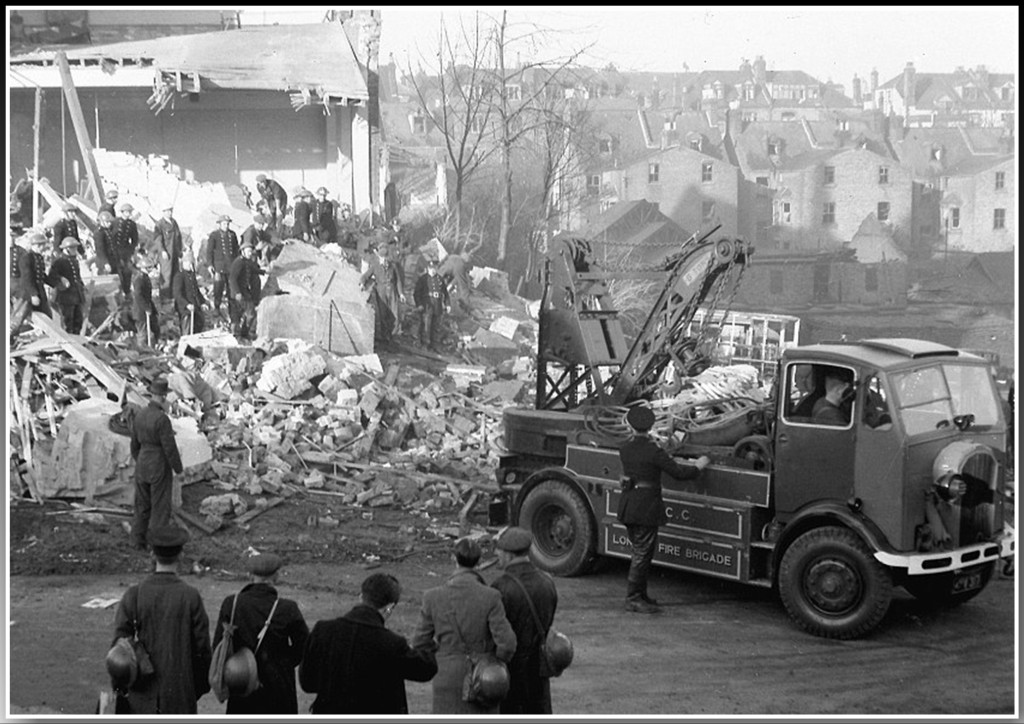

(Photo credit-London Fire Brigade.)

Some 2,000 London taxis were brought into service and used to tow trailer pumps. The taxis were large enough to carry a crew and the hose was stored in the luggage compartment. However, the accommodation was frequently poor at best and the new volunteer firefighters spent many hours making good their bases and building their own wooden beds. In addition to this they erected brick walls over windows and sandbagged entrances to protect themselves from blast damage.

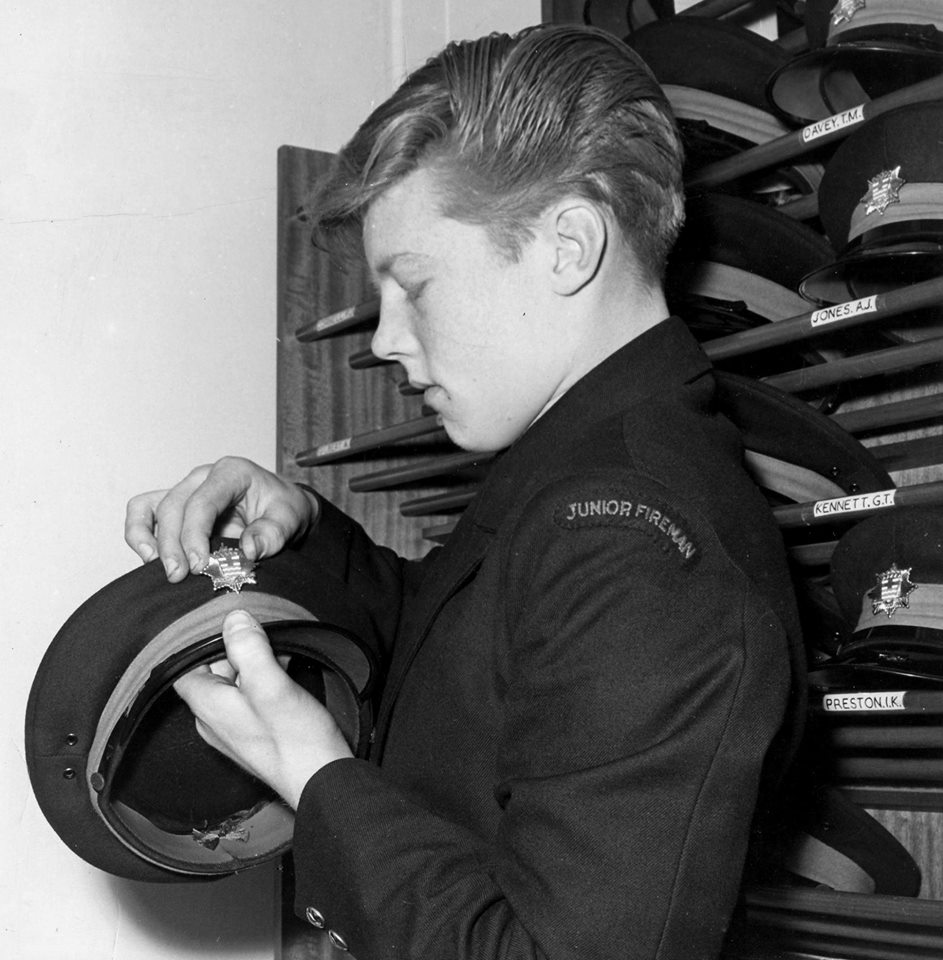

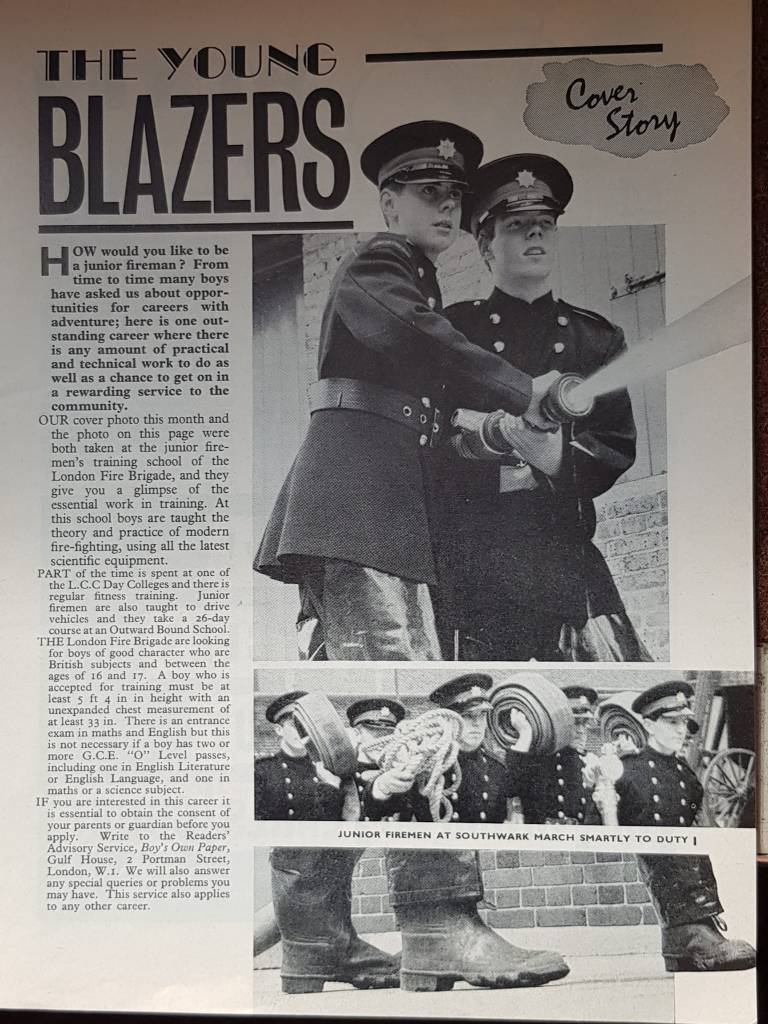

The basic training was provided by firemen from the London Fire Brigade. Detached from normal firefighting duties, they put the new recruits through 60 hours of practical and theoretical lessons. Whilst some women chose to undertake dispatch rider (motorcycle) duties and others opted for motor driving most were trained in ‘watchroom’ duties and necessary procedures for mobilising fire engines and pumping units. Everyone underwent basic firefighter training. They were, of course, civilians. They had volunteered from every trade and profession, from every walk of life. Office workers, labourers, lawyers, tailors, cooks and cleaners had taken up the call to join the Auxiliary Fire Service.

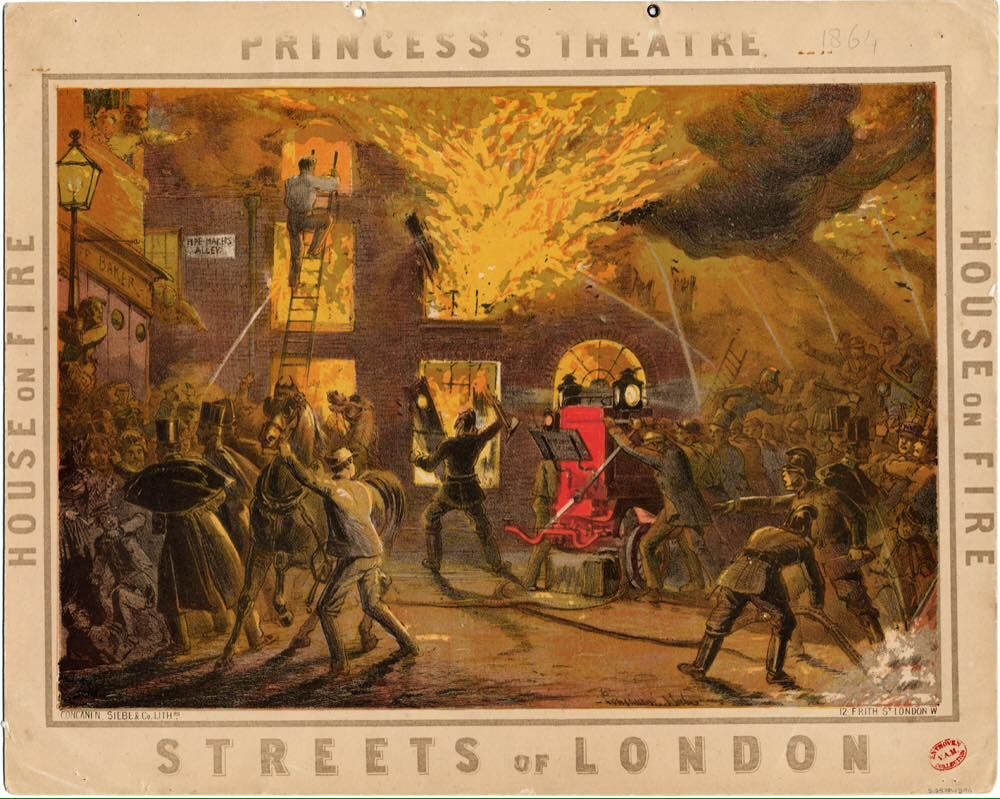

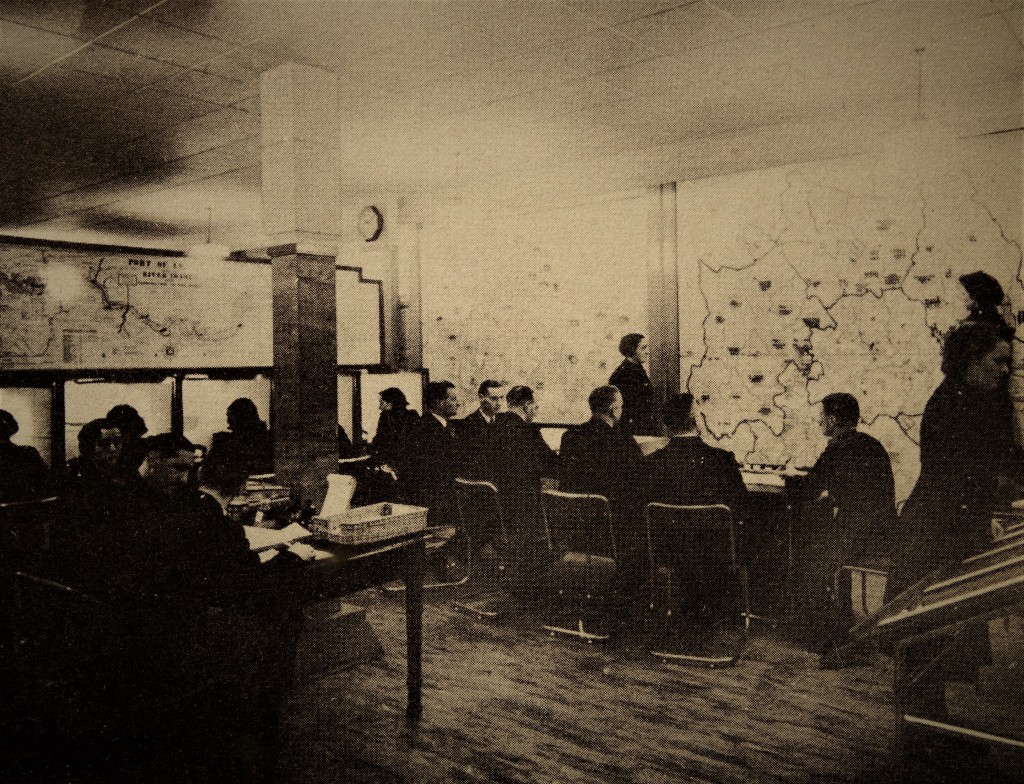

(Picture credit-London Fire Brigade.)

AFS recruits were divided into different categories. This was based on their physical capabilities, their age, gender and skills. Men considered Class B performed general firefighting duties. B1s worked only on ground level, either pump operating or driving. Others recruited from trades on the Thames were classed for River Service work and whilst women would be in the thick of it none performed frontline firefighting duties. Those youngsters under 18 years of age became messengers equipped with either motorcycles or pedal cycles.

Those auxiliaries who became full-time firefighters on the outbreak of war received a weekly wage. Firemen earned £3 per week, women got £2. Those aged 17–18 received £1-5 shillings and the 16–17 year olds got £1 a week.

7th September 1940.

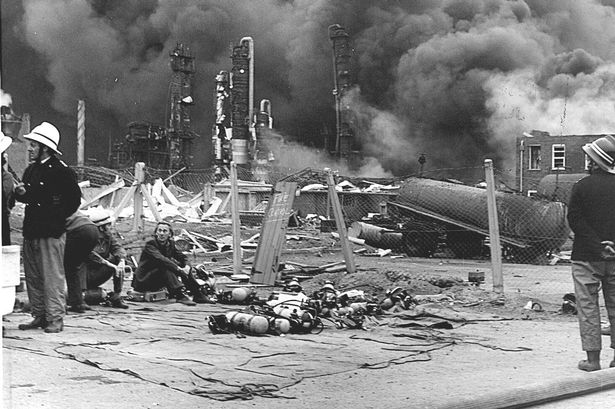

It was a lovely sunny day when, at 4.43 p.m. the air-raid sirens started over London. A 12-hour bombing attack was launched on the capital and the ‘all clear’ would not be sounded until 4.30 a.m. on the 8th. In that raid, 1,600 people had been seriously wounded and 430 killed. Swathes of London’s docks and the surrounding areas were either totally destroyed or left as smouldering ruins.

For that first night only one in five of London’s firefighters had had any previous experience. The dangers they faced were numerous and unpredictable. During the war, more than eight hundred firefighters would be killed and more than seven thousand, seriously injured. Many of them blinded by heat or sparks. At the end of the ten-week onslaught of intensive bombing on London fire-crews were utterly exhausted by lack of sleep, excessive hours, irregular meals, extremes of temperature, and the constant physical and mental strain.

On the river, beside the Massey Shaw and London’s other fire-fighting craft, London’s air defence precautions included the River Emergency Service. More than a dozen pre-war pleasure steamers were converted to first aid and ambulance boats. They were moored at various points along the river including Silvertown Wharf, Wapping and Cherry Garden Pier, alongside the Beta III. A taste of what the fire-float crews, and others, endured on the Thames that first night (7th September) it is perhaps best illustrated by a personal account given by Sir Alan Herbert, who was in command of the Thames Auxiliary Patrol’s vessel Water Gypsy, which was heading downriver:

“Half a mile or more of the Surrey shore was burning. The wind was westerly and the accumulated smoke and sparks of all the fires swept in a high wall across the river.” He pressed on into the clouds of smoke: “The scene was like a lake in Hell. Burning barges were drifting everywhere. We could hear the hiss and roar of the conflagrations, a formidable noise but we could not see it so dense was the smoke. Nor could we see the eastern shore.”

As dawn broke on the 8th September the scale of the destruction was revealed. In addition to the dead and the injured three main railway stations were out of action and one thousand fires were still burning, burning all the way up the river from Deptford to Putney. They included two hundred acres of timber ponds and stores in the Surrey Commercial Docks, destroying one third of London’s stocks of timber – timber which was badly needed for building repairs in the coming months.

London’s women at war-in this case serving within the AFS.

Women had worked as firefighters long before the outbreak of the Second World War. They had been employed by private brigades and others, like the one attached to the feminist Girton College in Cambridge- the first all-women “brigade” in the UK where students were taught by Captain Sir Eyre Massey Shaw, the first chief fire officer of the Metropolitan Fire Brigade.

When the AFS was formed in 1938, a huge recruitment drive was launched to attract women as their fathers, brothers and husbands were signing up to join the Royal Navy, Army and RAF. At the mid-1930s there were still only 4,272 professional firemen in the whole of the UK, with nearly half of them employed in the London Fire Brigade.

When war broke out in September 1939, and with the AFS some 100,000 strong the ‘new’ firemen we seen as potentially posing a considerable threat to the regular fire brigades. Then to add insult to injury, as some saw it that ‘women’ were being allowed to join too! It was not a popular move with many of the men in positions of authority in the service. One chief officer even refused to admit women, declaring: “I would rather resign than be made to drill young girls and women to be firemen”.

But such macho sentiments like these had relatively little impact thankfully. With firewomen numbers increasing from 5,000 in 1940 to 20,000 six months later in 1941, the year the AFS was removed from local and placed under government control (and renamed The National Fire Service (NFS)) the numbers would rise to more than 90,000 women enrolled in the NFS by 1943.

Driving in pitch dark. The women were not expected to extinguish fires, although some did unofficially. Most were in supportive roles; drivers and despatch riders (a far more perilous job than it sounds) which would involve driving in pitch dark during enemy air raids.

Many others worked in the control rooms, usually putting in very long hours, but the women who attended air raids and fought fires alongside men seem to have been written out of history.

An internal Home Office memo from 1941 states that women’s duties were telephone and watchroom work, although it accepted that “it is not inconceivable that ultimately women may be accepted for observation duties and even as pump operators”.

Former FBU official Terry Segars writes in a later FBU history, Forged in Fire: “The reality … was that firewomen were more widely involved in active work than is generally acknowledged, and they could often be found in the midst of things during the blitz, whether helping out on the pumps, in control rooms close to the centre of the severest raids or delivering supplies to firefighters.”

Twenty-five firewomen lost their lives during the war.

London’s river fire service.

At the start of the blitz there was no stand-alone river service. It was an integral part of the London Fire Brigade and the London Fire Region. In 1938 twenty auxiliary fire-floats (they were not called fireboats until the creation of the National Fire Service in August 1941) had been ordered by the London County Council. These additional craft supplemented the London Fire Brigade’s existing five fire-floats: the newest being the high speed ‘James Braidwood’. The Massey Shaw (commissioned 1935), the Beta III (commissioned 1926) and the oldest two craft the Gamma II and the Delta II, which although decommissioned had been brought back into operational service.

With its greatly increased numbers the boats, and a commensurate increase in river stations, London had the largest river-based firefighting force in its entire history. The additional boats, some of which were open whilst others had a small rear crew cabin, all carried two large capacity portable pumps, each with an eight hundred gallon per minute output. Mounted in the front of these ‘new’ craft was a monitor mounted on the front of each boat. Additionally the Brigade had seconded four Thames barrages. Each barge carried four one-thousand gallon per minute Dennis fire pumps and had twin holes cut in the stern plates. Six inch suction hose was fed through the holes and placed in the river. The barges, which could move in all directions, were manoeuvred by powerful jets of water from two of the pumps. The other two pumps on the craft were used to concentrate on dock and ship fire, although when moored all pumps could deliver the equivalent of five major land fire appliances.

The enlarged river force suffered its only fatality during the period of the ‘Phoney War’ when, on the 6th January 1940, River pilot George Sluman, who was employed by the LFB, was lost overboard when he fell from the Lambeth pontoon, opposite the Brigade headquarters building on the Albert Embankment. He was 53 and his body was recovered two weeks later on the 18th January at Southwark Bridge.

In addition the LFB’s four existing river stations, the Battersea station was reactivated after its closure in 1937, there were another nine stations from Richmond in the upper reached down to North Woolwich. In that first week of the Blitz much of the river service was constantly on station, if not actively engaged in firefighting them supplying vital water supplies to those that were. Unlike their land counterparts, on the river, there was nowhere to run for cover. Occasionally the fires would come to them as blazing steams of molten poured for the quayside and onto the water.

( Following the Blitz, which ended in May 1941, lessons had been learned from bring together differing brigades to fight major conflagrations. At times this led to misunderstanding and confusion with mismatched equipment and chains of command. In August 1941 the National Fire Service was created, it came into being on the 18th of that month. Contained in the London Region was the newly created River Thames Formation. It brought together the now renamed ‘fireboat’ stations of London, Kent, Surrey and Essex. It covered an area from Tilbury to Walton-on-Thames. Fifteen new river stations were added and the river firefighter’s strength had increased to 386. The now had a fleet of 30 fireboats and 40 adapted barges. Each pontoon was large enough to have two fireboats and two or three barges moored alongside.)

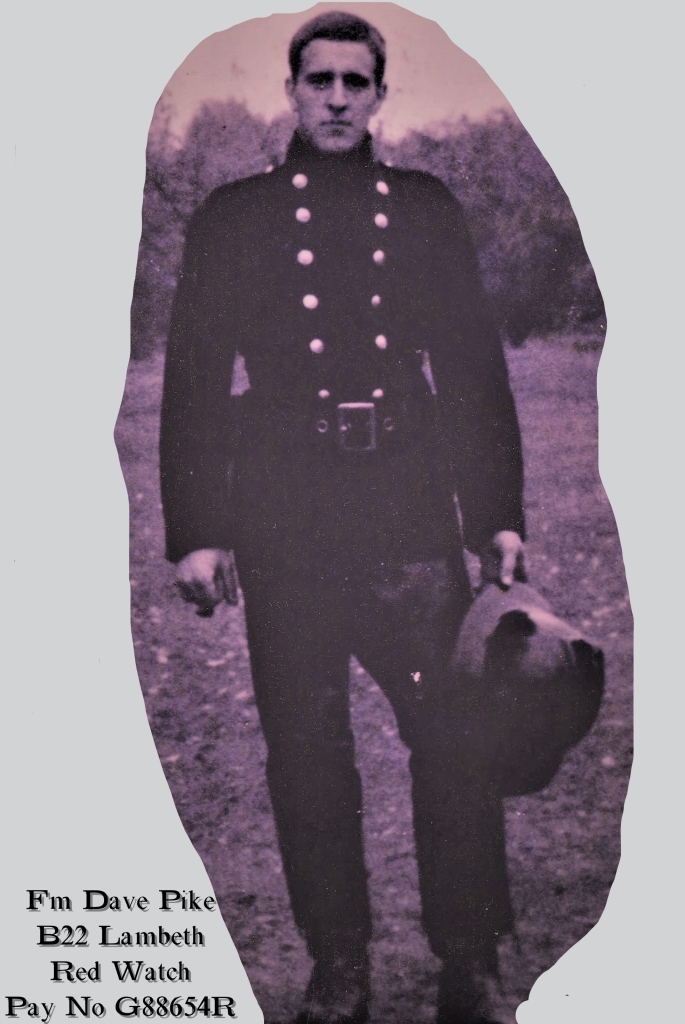

An AFS fireman’s tale.

“At that time, there was quite a lot of friction between the London Fire Brigade members and the AFS. We were regarded as young upstart amateurs but as events proved, we were just as professional as they were.

At one time, their helmets were painted bright red so they were instantly recognisable as LFB men. I was stationed at Holloway, at sub-station 76X. We had three LFB men in charge of us, each whose rank was no higher than Fireman, but they had been given charge of the sub-station because of the emergency situation. One of these men was a big, well built, abrasive type of man. When he gave instructions at drill time he would use three swear words when one would have been more than enough.

One night, North London appeared to be getting more than its fair share of a heavy air raid. At Holloway, we had six appliances available and one by one they were ordered out to various incidents until only one was left of which I was the driver/pump operator. The man in charge of us was this particular LFB man. We were sent to an incident in the Finsbury Park area which turned out to be a warehouse behind a row of terraced houses.

Access was by a long wide yard between two houses. We saw that water was pouring down this yard like a river in flood. Our intrepid No 1 said;

“Follow me.”

So in single file, we splashed our way up the yard. I was immediately behind our leader when suddenly he disappeared! We could hear a lot of muffled cursing and splashing and looking down. All we could see was a red helmet just above the water line.

The other two crew members and myself managed to grab his shoulders and yank him to his feet. There was this big arrogant man looking like a drowned rat. We dare not laugh otherwise I think he would have killed us. It seemed that someone in their wisdom had removed the cover of a rather deep man hole to enable some of the excess water to get away and our No 1 became its first victim.

by ASF Fireman-George Woodhouse (Touse).

Falling from the skies.

Four-fifths of all bombs dropped during the Blitz were high explosives (HE). The German war machine constructed them of thin steel to maximise the effect of the blast, and they varied greatly in size. Some had a cardboard tube (like an organ pipe) attached which emitted an eerie whistling sound as the bomb plunged to earth. They were expressly designed to terrify the civilian population.

The smallest, and most common, were the 110lb bombs. There was also the 2,200lb bomb, nicknamed “Hermann” (named after the portly Hermann Goring). Then there was the “Satan” (4,000lb) and the largest bomb dropped on Britain was the “Max” that weighed 5,500lb.

The parachute bombs were very effective as they floated down and did not penetrate the ground. The damage they caused was widespread. Designed to smash through modern pre stressed-concrete industrial buildings in residential areas. The author of London at War 1939-1945 pointed out “as soon as one was seen falling, people would begin to move towards it: partly, perhaps, because they mistook the mine for a descending German pilot who needed to be lynched or apprehended; more probably because they wanted the silk of the parachute to make skirts or dresses.”

Incendiary bombs were small, but were very dangerous, as they could start fierce fires where they fell unless they were extinguished swiftly with sand or water. Thermite magnesium incendiaries were about eighteen inches long and only weighed around two pounds each, so thousands could be carried by a single plane. When ignited by a small impact fuse, the magnesium alloy would burn for ten minutes at a temperature that would melt steel, and metal particles would be thrown as far as fifty feet.

The George Cross was instituted on 24 September 1940 by King George VI. … I propose to give my name to this new distinction, which will consist of the George Cross, which will rank next to the Victoria Cross, and the George Medal for wider distribution. The medal was designed by Percy Metcalfe.

The George Cross remains the second highest award of the United Kingdom honours system. It is awarded “for acts of the greatest heroism or for most conspicuous courage in circumstance of extreme danger”, not in the presence of the enemy, to members of the British armed forces and to British civilians.

In 1940, during the height of the Blitz, there was a strong desire to reward the many acts of civilian courage. The existing awards open to civilians were not judged suitable to meet the new situation, therefore it was decided that the George Cross and the GM would be instituted to recognise both civilian gallantry in the face of enemy bombing and brave deeds more generally.

Announcing the new awards, the King said:

“In order that they should be worthily and promptly recognised, I have decided to create, at once, a new mark of honour for men and women in all walks of civilian life. I propose to give my name to this new distinction, which will consist of the George Cross, which will rank next to the Victoria Cross, and the George Medal for wider distribution.”

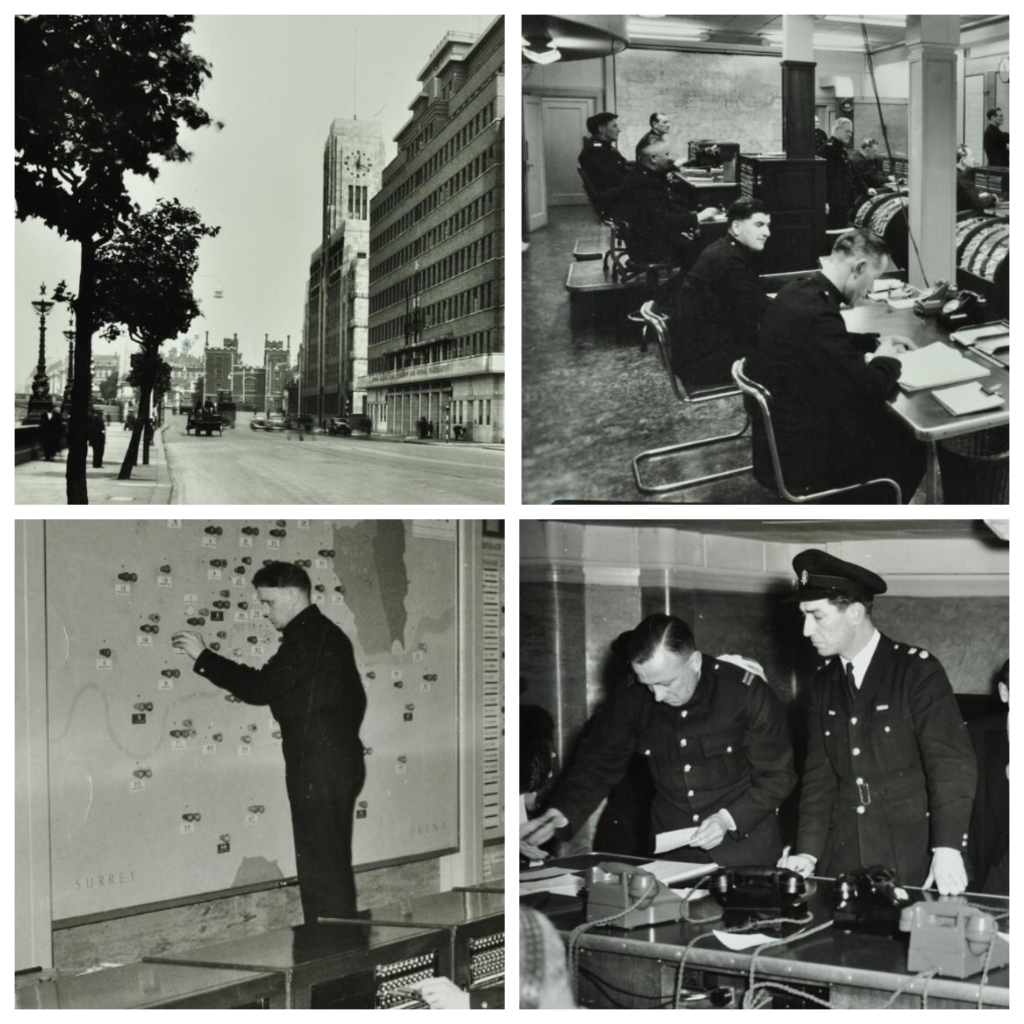

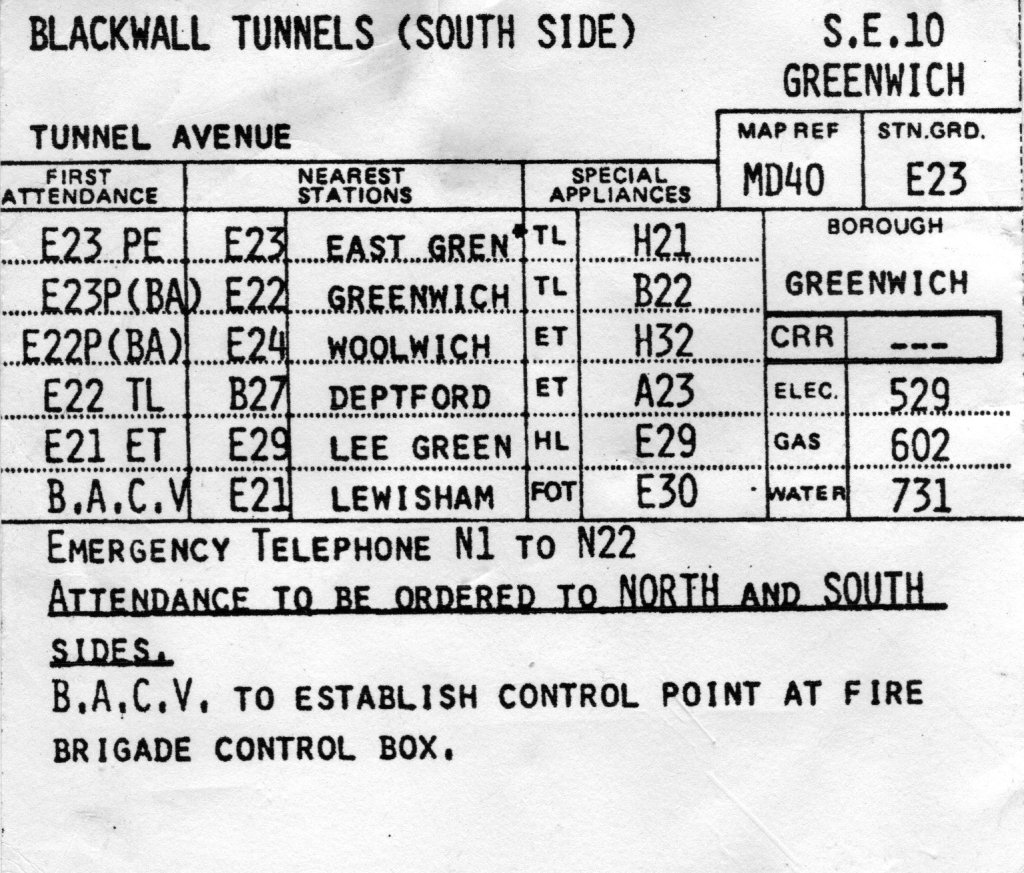

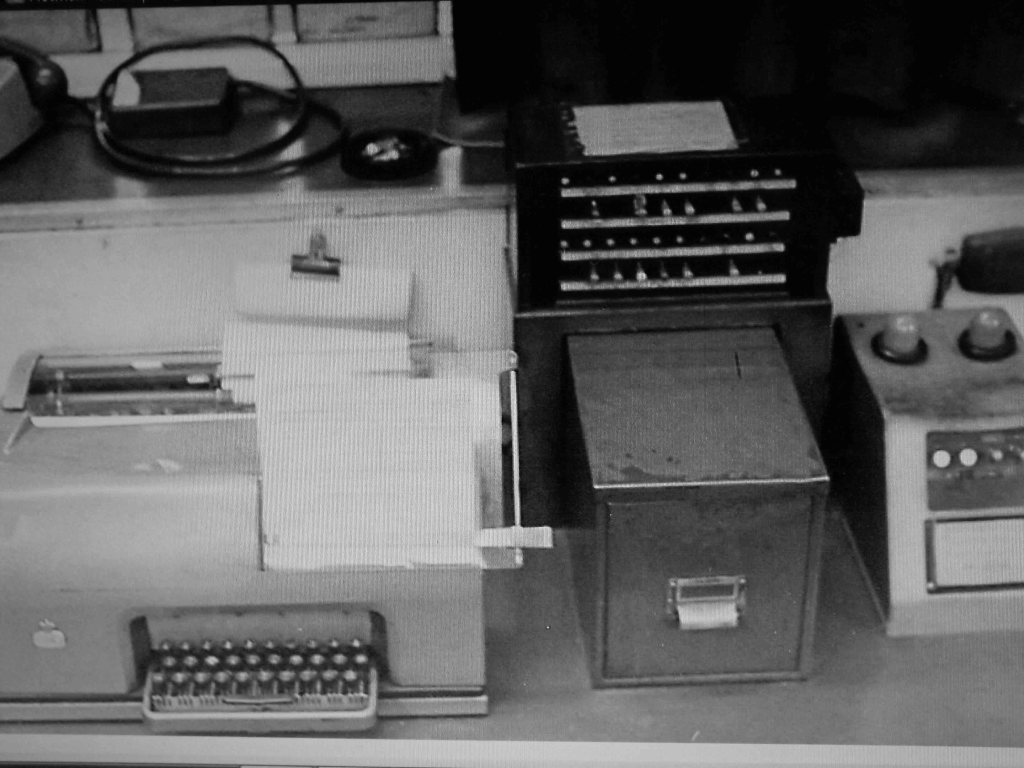

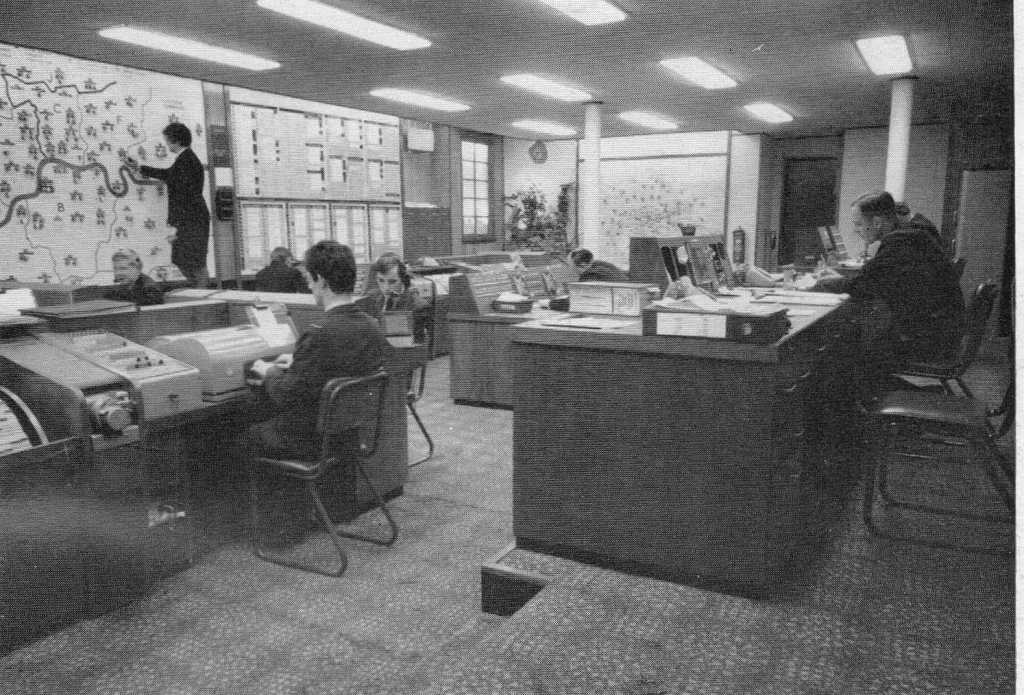

Blitz-Control rooms.

Control rooms were interesting places to be when their neighbourhood was under attack. Fire calls would pour in in by telephone and messenger, and it need an orderly system and well-trained operators-almost all women-if confusion were to be avoided.

Priorities and reserves presented many difficulties. If Mrs Brown rushed frantically into the station to say that her roof was blazing, was it possible to reply:

“We are sorry madam, but the fire service is reserving its last remaining appliance lest something more essential to the war effort than your house should catch fire, for example, the adjoining engineering factory of the nearby telephone exchange.”

There is much to be said for the slogan: ‘The fire that is burning is worth more attention than the fire that may never occur’. Important building around the capital have their own first-line fire defence, which could hold the fort until reinforcements arrived. On one occasion it happened that a message was passed by a fire station to a control at a higher level: ‘Called to a fire at Buckingham Place; no attendance from this station. On another occasion no immediate help was available when the House of Commons was hit by incendiaries.

Control room decisions were sometimes very difficult.

The Evening News-Tuesday October 1st 1940. By a Special Correspondent.

L.C.C. officials are tackling the job of making things as comfortable as possible for London’s heroic A.F.S. men and women. There have been little grumbles lately about the canteens and accommodation-chiefly lack of hot meals and drying facilities for cloths after long nights of dangerous firefighting. Ever effort is to be made to prevent any such troubled in the future.

Professional cooks have now been engaged at all stations and sub-stations so that meals can be prepared at any time and the number of field kitchens for use where there is any interruption of gas supplies is to be increased so that there will no hold-ups.

Emergency heating arrangements are being made to ensure the quick drying of saturated cloths.

In addition, it will be possible that extra premises will be acquired so that firemen temporary transferred from one station to another will not be overcrowded.

W.A.F.S. Helped: In the early days of the war the A.F.S. provided their own cooks. At some stations ‘W.A.F.S.’ took over the job-at others men who had had some experience. A few clubbed together to hire a cook. But when their work became arduous the Council [LCC] decided that cooks should be attached to all stations. This has now been done, and it is hoped that supplies of hot meals and drinks will always be ready when the firemen come off duty.

On the Spot: Mobile canteen vans now go around to all big fires started by incendiaries so that the firefighters may have and snacks on the spot.

But it is realised that men who have fought fires through intensive raids for perhaps eight hours or more want a hot meal before “turning in”.

An official of the L.C.C. said to me; “Everything possible is being done to ensure that the catering and accommodation are the best possible.” “There is plenty of food and all stations have facilities for cooking. With field kitchens to fill the gaps there should be no trouble.”

Station 72 – Soho Fire Station – 7 October 1940

Shaftesbury Avenue in W1 was bombed on several occasions during 1940 and 1941. On the 24th September 1940 two high explosive bombs hit the intersection of Shaftesbury Avenue and Wardour Street damaging the Queen’s Theatre and St Anne’s Church, Soho. There were four casualties were reported but no fatalities. The buildings were assessed as dangerous when inspected by the Rescue Services. The next day, 25 September, an oil incendiary bomb hit near the intersection of Great Windmill Street and Shaftesbury Avenue bursting a water main.

Then at 7.45p.m. on 7th October – after four nights in which Westminster escaped damage in the enemy raids on London – a high explosive bomb hit the doorway of Soho fire station, located at 72 Shaftesbury Avenue and close to Cambridge Circus, directly opposite the Palace Theatre. The Shaftesbury Avenue station (built in 1887 and renamed the Soho Fire Station in 1921 after the London Salvage Corps moved out) suffered severe damage and was virtually demolished. The station was replaced by a temporary structure-a structure that remined in place until 1983, when the current station was erected on the same site.

The dust was thick in the air and rubble, forty feet high, spreadeagled itself across Shaftsbury Avenue and onto the frontcourt of the Palace Theatre. Two passers-by sheltering in the doorway were killed outright and several of the firemen inside, sheltering in the basement emerged, covered in dust and some very shaken, but generally unhurt. Some firemen remained trapped in the watchroom, the entrance to which was completely blocked by fallen rubble.

When the first supporting crews from the near-by sub-station arrived, they found that not only had the Soho firemen from the basement released their colleagues from the watchroom they had also removed the three dust laden fire engines, two staff cars and two dispatch rider bikes from the station too. However, two were still missing. They were LFB Station Officer William Wilson and AFS Fireman Frederick Mitchell. It would take two days before their bodies were finally recovered.

The Evening News, in its edition on Tuesday 8th October gave back page coverage to the ‘ALL-NIGHT LONDON RAIDS. Towards the tail end of the lengthy update was the sub-heading ‘FIREMAN KILLED’. The paper commented;

‘One fireman is dead, one is missing, and three are severely injured as the result of a bomb on a London fire station. The rest of the staff of the station got out of the debris unharmed.’ It was not the first tragedy to befall those attached to station 72 Soho. Seven Auxiliary firefighters died when a bomb hit the AFS sub-station at Jackson’s Garage in Rathbone Place (72X). It occurred around midnight on 18th September 1940, and Soho’s AFS substation was directly hit. The explosion demolishing the building and killing civilians as well as seven members of the AFS.

EXTRACTS FROM THE MEMOIRS OF FIREWOMAN. WINIFRED SLEET A.F.S. AND L.F.B.

“The blackout was a real hardship. Coming out of a well-lit room into the street was often fraught with danger if there was no moonlight. Once I found myself half blind, despite carrying the regulation torch, with its light blocked out by tape leaving just a tiny beam. Walking into the railing around a tree I suffered a black eye and split lip. That night, the now regular air-raid, a bomb fell on the bridge over the railway opposite. The bridge formed part of Liverpool Road which ran along the top of our street. I was on duty and went outside to look up towards the bridge. The buildings were still standing, minus the windows. It was a night to remember, as not long after, one of the men came in to say there was a strange swishing noise in the yard. We all went outside, and someone spotted a parachute dangling from the broken guttering, high up.

What seemed to be a long dark object was swinging around beneath it. At first, we thought it was an airman but it wasn’t the right shape, so we broke all the regulations and shone a torch up towards the roof. It revealed that what we were looking at was a land-mine capable of flattening the whole street. The station personnel, and any residents left at home in the street, were evacuated in minutes, and once again the bomb disposal unit came to our rescue.

As the raids continued stories began to circulate around the fire stations. We heard tales about warehouses in the docklands area, and how their contents were scattered in the bombing. Of fur coats and bales of expensive cloth and silks, floating down the gutters. Of the rivers of boiling sugar syrup from the Tate and Lyle sugar warehouse, and the horrors of the burning and exploding tins of paint. Paper was the worst, it smouldered for weeks, despite continual hosing down. When the perfume contents of the “Evening in Paris” stores were hit the bottles burst open and liquid perfume ran into the gutters. All the fire appliances in that area, had the wheels soaked in the stuff, and the fire stations reeked of perfume when the appliances returned. We heard that it put the men off their food it was so bad.

A lot of the casualties were men, fighting fires, on the boats and jetties. If they slipped and fell into the Thames, whilst wearing full gear of uniform, waterproofs and heavy boots, it was fatal unless a colleague saw them and got help.”

Balham. 14th October 1940.

Tragically, Underground stations were not always the safest places to be. Over 60 would be killed at Balham underground station in October 1940 when a bomb hit the street above the station and collapsed the tunnels below. The bomb burst a water main and the combination of water and soil meant some drowned in the resultant slurry.

It was on the evening of the 14th that one of the worst wartime disasters involving the London Underground took place. With German bombers overhead people had taken to the shelters, in south-west London this included the platforms at Balham underground station. Many trains were still running and commuters would be stepping over people using the station platforms for protection.

Although just 43 feet (13 metres) below ground, the Balham platforms were considered deep enough to be classed as an official shelter point. At exactly 2 minutes past 8 p.m. a bomb hit Balham High Road above the station. It caused a massive crater in the ground, and fractured a water main below ground. A bus, unable to stop, drove into the crater. It was an image of the London bombing that was circulated around the Allied globe.

The local Balham people had gone down into the Tube for safety, but instead they found something worse than the bombs. What they found was unknown, terror, women and children, small babes in arms, locked beneath the ground in a new Hell. One involving the power of water plus a cloud of gas. Those not killed outright were tragically either suffocated or drowned like rats in a cage.

The initial number of dead was unclear. Reports ranged from 64 to 68 people, although the Commonwealth War Graves Commission now officially records 66 deaths due to the flood of water and soil into the tunnel. In addition, more than 70 people were injured. What was certain is when the bomb actually struck: the clock on the underground platform stopped at 8:02pm.

Below ground the crater had struck right above a cross passage between the two platforms. Debris filled the short corridor however, with the water main broken the force of nature took an unkind hand as the water shifted vast quantities of soil into the tunnel system.

Mr Colin Perry was to later recount how the disaster was told to him. “The water main was burst and the flood rolled down the tunnels, right up and down the line, and the thousands of refugees were plunged into darkness, water. They stood, trapped, struggling, and panicking in the rising black invisible waters.”

Confusion reigned and rumour and gossip were already talking about hundreds of dead at Balham. But an inspection by Lt-Col. AHL Mount, the Chief Inspecting Officer of Railways at the Ministry of Transport the following day dismissed many of the claims as exaggerated. But his report gave a graphic insight into the aftermath of the disaster, as the London Fire Brigade was still pumping water out the following day and one of the three broken water mains was draining “into the crater like a small waterfall.”

It took several months to clear the site with bodies still being recovered in late December. The line, which had been suspended between Tooting Bec and Clapham Common was reopened on the 8th January 1941, with the station reopening on the 19th January.

The week of 10th -17th October 1940.

By the first week of October 1940 four LFB fire stations and seven AFS substations had been hit and put permanently out of action. At each there had been serious casualties.

Any raid could bring oil bombs, high explosive land mines, incendiaries, and parachute mines. Each had its followers in the shape of raging fire, falling debris, and choking smoke. South of the Thames, in Southwark, one such major blaze involved the Blackfriars Goods Yard on Friday 10th October.

However, using the London Underground as a mass air-raid shelter was not without its difficulties and its risks. Journalist Alison Barnes proclaimed at the end of her newspaper article, ‘that the airlessness, the lack of real ventilation was far more disturbing than all the noisy concrete horrors of London above ground.’

Footnotes.

- London had been bombed for 57 nights. The enemies last consecutive raid came on November 3rd 1940. Although London would continue to attracted the devastating, and deadly, bombing raids like a magnet, the Luftwaffe had spread its net wide across the country. A new term ‘to Coventrate’ [meaning to ‘devastate by heavy bombing] entered the language after Coventry was attacked by the light of a full moon. Local factories, roads and railways were destroyed and 568 people were killed.

- Merseyside received the unwanted accolade of being the second most heavily bombed place in the country. Hull, Swansea, Southampton, Portsmouth, Belfast, Bristol and Avonmouth also suffered. Clydeside, which had hoped it was out of range, was bombed in March. Not a single pub was said to be left standing. Over 4,000 homes were destroyed or damaged beyond repair in an already desperately poor area.

- As the bitter winter bombing dragged on few places escape attack. The main targets are ports, ship yards and naval bases and major London raids in December through to early 1941..

- In the eight months of attacks on greater London, some 43,000 civilians were killed. This amounted to nearly half of Britain’s total civilian deaths for the whole war. One of every six Londoners was made homeless at some point during the Blitz, and over 1 million houses and flats were damaged or destroyed. 327 of London’s firefighters lost their lives.