Certainly, within the City of London and that of adjoining Westminster fire cover had, since the early 1700s, been the prerogative of the private independent insurance companies. It remained that way until 1832. In that year the majority of insurance companies combined their forces, forming the London Fire Engine Establishment (LFEE), a single fire brigade made up of those previously independent.

The amalgamation of the Insurance brigades helped to remove some of the chaos, reportedly, frequently occurring at fires. Whilst the LFEE remained a private body, it was nevertheless recognised as the public fire service for the London area. An advert running on 1 January 1833 announced its goal was to provide better fire protection to the inhabitants of the Metropolis. But in 1862, when John Drummond, Esq., Managing Director of the Sun, and Chairman of the Committee for Managing Fire Extinctions, was questioned on the ‘principles on which the LFEE had been formed’ he replied ‘solely for the protection of the offices; it is an association of nearly all the offices in London’ (House of Commons, 1862).

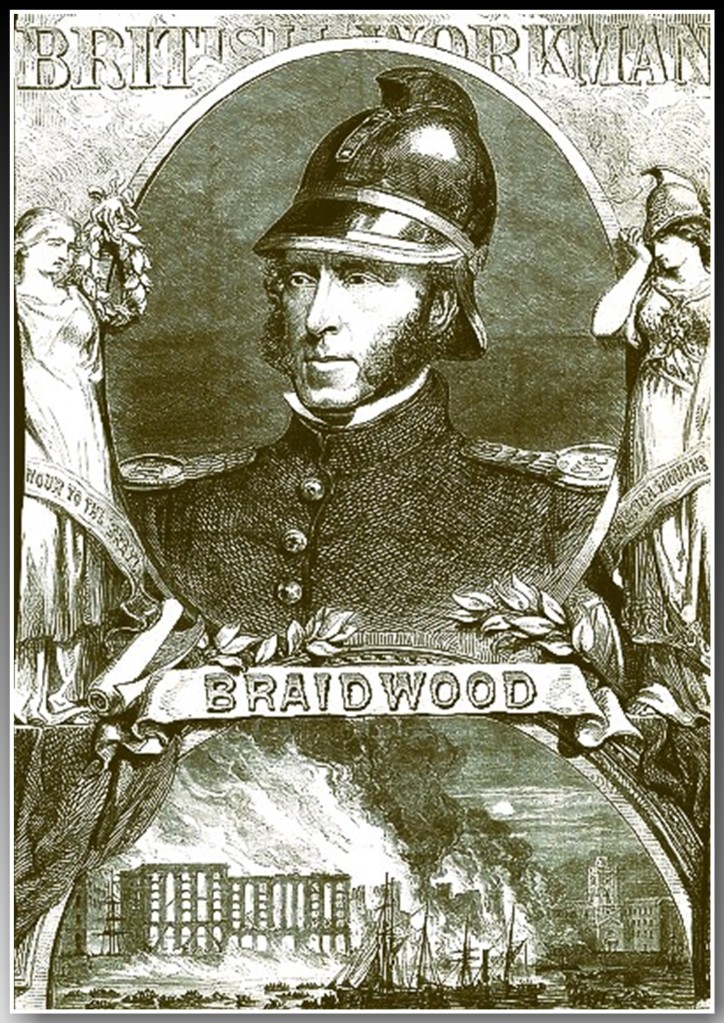

James Braidwood, a Scot, led a force that consisted of 80 watermen and had 17 land and two river stations. The now Superintendent Braidwood, who had previously run the Edinburg brigade, brought with him formal training programs for his new firemen. He also required that they have working knowledge of the district to which they were appointed. However small the LFEE was considered to be a very efficient organisation at the time. But, according to the Phoenix Assurance and the Development of British Insurance, the large insurance offices did not consider the protection the Brigade provided adequate for the City of London. They preferred fire protection to be publicly provided. London was expanding rapidly. The cost of protecting the metropolis from fire in 1833 was £7,988. By 1865 the cost had risen to ₤26,005.

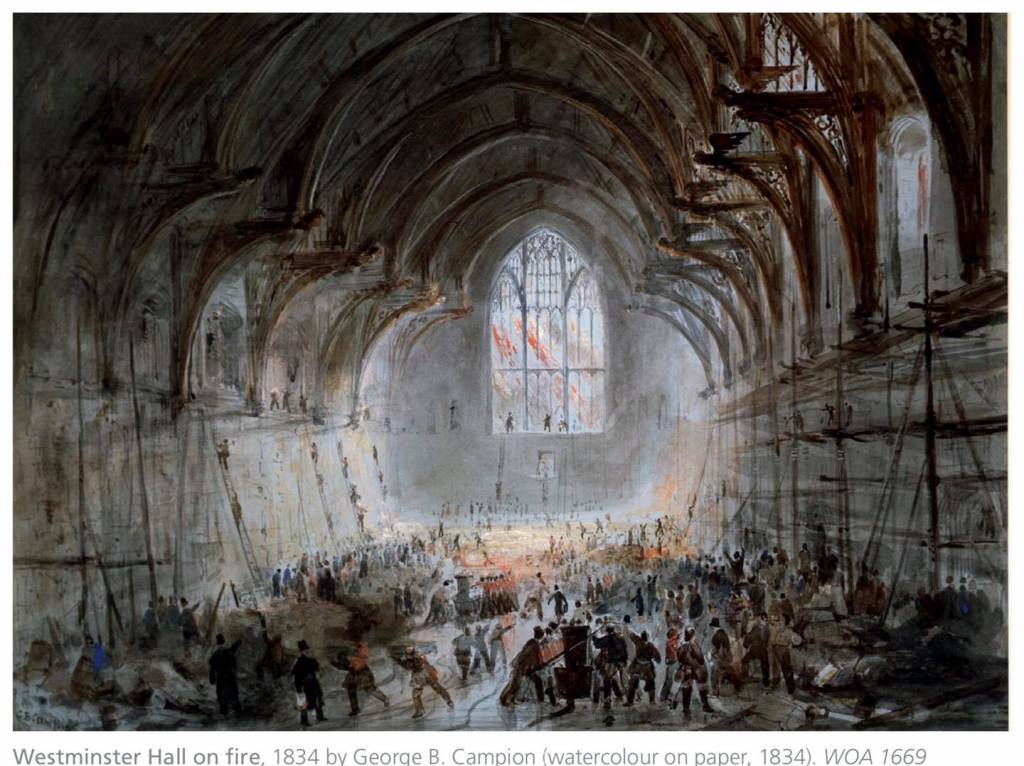

The Insurance companies were becoming acutely aware of the financial strain of fire protection. They sought opportunities to rid themselves of this burden. The insurance companies, involved in the LFEE, expressed their concerns over shouldering the duty of fire protection, therefore relieving the government of this duty. In a letter to the acting Prime Minister, and following the fire in which the Palace of Westminster (Houses of Parliament) was almost totally lost, they cited concerns were the failing conditions of the parochial engines and possibility of an insured property and an uninsured property catching fire at the same time.

Although the Insurance companies were willing to provide services to all in need, they were responsible only to their employers and through them to those purchasing insurance. Therefore, Insurance companies were not required to provide assistance to uninsured property, including public buildings. The insurance companies explained ‘….if during the late conflagration at Westminster, any insured property in danger, or any simultaneous fire or fires in other parts of the town, had imperatively called upon the Superintendent to devote the service of the engines elsewhere, Westminster Hall and the public property adjoining must have shared the fate of the two Houses of Parliament’.

The acting Prime Minister replied indicating ‘…the interference of Government would be productive of little benefit, while it might and probably would relax those private and parochial exertions which have hitherto been made with so much effect and so much satisfaction to the public’. The LFEE continued to supply fire protection to London for the next 30 years.

“The whole Building, if once fairly on fire in one floor, will become such a mass of Fire, that there is no power in London capable of extinguishing it, or even of restraining its ravages on every side and on three sides it is surrounded with property of immense value.”

Time would sadly prove the accuracy of James Braidwood’s warnings.

With London expanding, and the cost of fire-fighting growing, insurance companies struggled to continue to provide the service. It was clearly not a profitable endeavour for them. They were paid to provide insurance not to fight fires. The cost of offering fire protection now outweighed the benefit to them. Furthermore, because insurance companies were paid to provide insurance, an incentive existed for the offices to protect insured homes. An issue could certainly arise if both an uninsured property and insured property caught fire at the same time. The insurance companies would focus on the insured property and the uninsured would follow after.

There was no incentive for insurance companies to correct this problem because they were not paid to fight fires. The government however felt the services provided were adequate and turned its attention elsewhere. In 1836 The Royal Society for the Protection of Life from Fire was formed. It followed in the footsteps of the Fire Escape Society (1828), an organisation set up by philanthropists in reaction to the high death rate in domestic property fires. The Royal Society for the Protection of Life from Fire provided escape ladders at fires, working alongside the LFEE to protect the citizens of London from fire.

Pre the LFEE London parish pumps, volunteer firemen and individuals owning and operating firefighting equipment continued to exist. Parishes while, perhaps, providing some assistance at fires had not improved the condition of their equipment. Volunteers continued to supplement the private brigades’ coverage, providing a great assistance to Braidwood and his force that were responsible only for the insured property located primarily in the centre of London. Despite having concerns about the fire service brought to its attention, the government declined to become involved.

Braidwood was killed in 1861 at a fire in Tooley Street. His death was said to have created confusion and disorganisation at the fire since there was no one appointed to lead in his absence. Further, the economic implications of the fire were profound. It cost the insurance companies over £2,000,000. The Insurance companies attempted to raise premiums, some by as much as 300 per cent. This created a loud response from both merchants and other business men who believed the size of increase was unjustified.

The insurance companies tried yet again to relinquish their fire-fighting duties. In a letter to the government, insurance companies note that ‘without any public authority whatever it [the LFEE] has for nearly 30 years extinguished the fires which have occurred in the metropolis and surrounding districts without inquiry and without charge’. The insurance companies pleaded for reconsideration of the state of the fire service: ‘In the opinion of the Committee such an increase in the number of fires and in the expenditure incurred, rendered a reconsideration of the whole subject imperatively necessary, more particularly as they were satisfied that a system for the extinction of fires which might formerly have been adequate for the metropolis, has now become very insufficient for its present greatly extended limits’ (House of Commons, 1862).

In response to the post Tooley Street uproar, a Select Committee was established to evaluate the system of fire protection in London. The Committee interviewed many witnesses to prepare its report discovering among other things that the insurance companies had been operating at a loss for some time. When John Drummond, Esq., Managing Director of the Sun was questioned regarding premiums he indicated that competition was such a factor that he doubted an increase could be carried into effect. Drummond was also asked why the insurance brigade (LFEE) would pay for fire extinction at all houses, to which he replied: ‘There is no reason why we should do so; we do so on the principle that it is our interest to put out every fire; that this house may not be insured, but that the next may, and that the one not insured may set fire to the other’ (House of Commons, 1862).

The report produced from the Committee noted that the insurance companies had agreed to supply fire suppression ‘so long as the expense was moderate’; however, the cost of the duty had now grown to a ‘magnitude’ which the insurance companies believed ‘they cannot continue to bear’. The report noted that of the £900,000,000 of insurable property only about £300,000,000 was actually insured. The final report also noted that the LFEE ‘as far as their means would enable them, have performed most ably and most efficiently. It has, however, been equally admitted by every witness that the present scale of their staff, engines, and stations is totally inadequate for the general protection of London and its immediate vicinity from the dangers of fire. This detail was admitted by the new Superintendent of the brigade, one Capt. Eyre Massey Shaw. (Appointed after Braidwood’s death.)

However, the Committee concluded that they consider the LFEE efficient for the protection of that part of London where the largest amount of insured property is located. They had no desire, or intention, to add to their expense by placing additional fire stations in situations where, if a fire occurs, it is not likely to cause such comparative injury to the offices as if it occurred in the water-side warehouse near the City. The final report from the Select Committee, and the details leading up to it, shed more light on why the insurance companies fought so hard to relinquish the duty of fire protection. The recurring argument that the cost of firefighting was rising significantly and the Insurance companies were not getting paid to fight fires.

There was a severe free-rider problem because of the difficulty of excluding uninsured properties. Premiums on the one-third of property in London that was insured were covering the cost of fire protection for the remaining uninsured two thirds. Even if competition had not impeded the implementation of increased premiums, it would have only affected those individuals already paying for the service. To operate profitably the insurance companies would have needed to find a way to charge individual home owners for fire protection, separate from the charge associated with insurance.

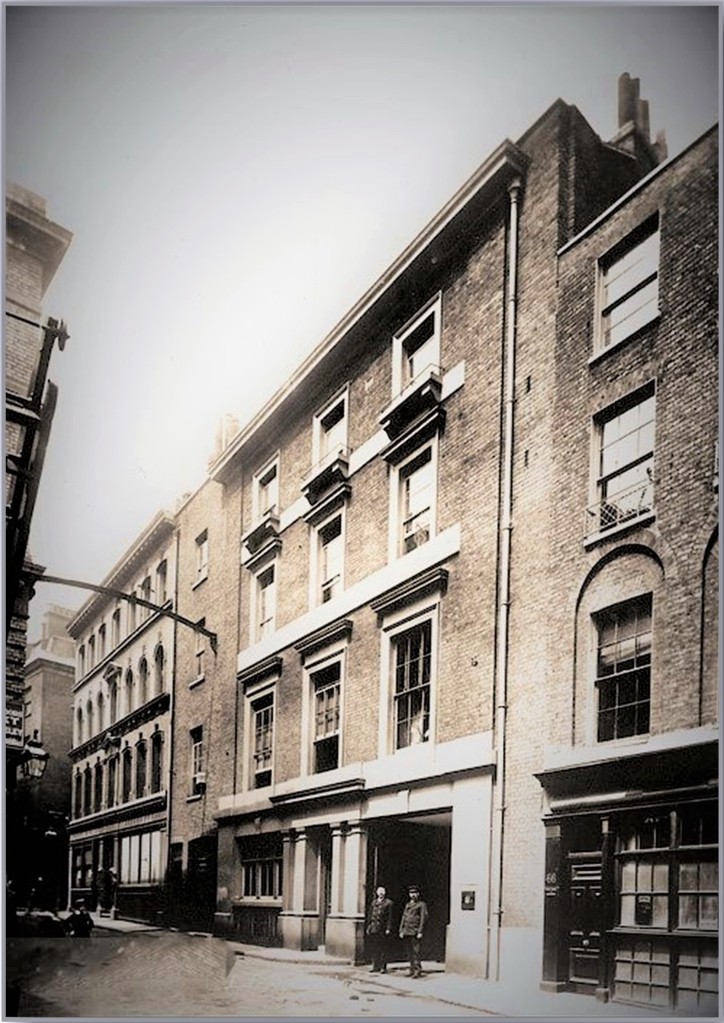

(It also remained the headquarters station of the Metropolitan Fire Brigade until a new headquarters was built for Capt. Shaw. It was opened in 1878 in Southwark Bridge Road. SE1.)

(Picture credit-London Fire Brigade.)

Alternatively, insurance companies needed to find another body to assume the duty of fire protection. Following the Report an Act was passed in 1865 to transfer fire protection into the hands of the Metropolitan Board of Works (MBW), a public authority. Public provision of fire protection began in London on 1 January 1866. The new Metropolitan Fire Brigade was created. With it a new post too, that of Chief Officer, the first being Capt. Shaw. The Insurance companies and parishes were officially relieved of their fire-fighting duties. Both were required, however, to contribute monetarily to the new public brigade. Insurance companies were mandated to pay at a rate of ₤35 per million gross insured (House of Commons, 1862). Those previously providing brigades were now required to pay for the service. In addition, insurance companies remained actively, and voluntarily, involved in monitoring the efficiency of the new institution. They served up recommendations for improvement of the fire service, including the development of several smaller stations versus fewer larger stations. Still with insurance cost concern the Insurance companies also formed the London Salvage Corps and in doing so deprived the new brigade of some its former firemen!

In addition to assuming the firefighting duty, the MBW through the MFB, also took on the services previously provided by the Royal Society for the Protection of Life from Fire. This transfer was driven by the Society which had experienced a drop in income. Additionally, the parishes which were now paying for fire protection believed protection of life should be included as part of their payment. The MBW eventually succumbed and took over the duty.

The transfer of firefighting from the private to public sector was not without difficulties. The financial situation was dire. The budget set for the brigade was tight and borrowing power of the MBW was restricted. The MBW received funds from the parishes and the insurance companies, as well as the government. Yet, financial troubles ensued. The new brigade had difficulty taking over mortgages of existing stations from the insurance companies, not to mention the need to build new stations where no coverage had been in place.

The working conditions for the firemen worsened under the MBW Firemen were forced to work longer hours, and in uncomfortable settings. Pay and funds provided in the event of a loss were slashed: the LFEE had paid families of those lost ₤10 to cover funeral expenses, but the Board paid only £5. The MBW faced a serious manpower issue, fuelled by the small budget and the growing metropolis.

The early years for the new Chief, Capt. Shaw, were challenging to say the least. On its very first day the MFB faced its first major blaze at St Katherine’s Dock. In truth it was still the old brigade with just a new name. But in the years that followed Shaw moulded a brigade that became the leading fire brigade in the civilised world.