It was later determined that the fire had most likely been smouldering since Saturday night, after the wharf had closed for business on 31st October. It had been an exceptionally busy few weeks for the London Fire Brigade. Only eleven days earlier, on the 20th October, the brigade had tackled a massive blaze at the Southwark Hop Exchange, Southwark Street, in the shadow of the Brigade’s headquarters. So serious was the blaze that many appliances were mobilised within minutes of the first call. Forty motor-pumps, four turntable ladders and other special fire engines fought the blaze and within a couple of hours the fire was thought to have been brought sufficiently under control that only four engines remained at the scene. Suddenly some hop dust exploded in the part of the building that had been saved. It very quickly involved the whole of the western ends six upper floors. Once again tens of fire engines had to attend the scene and it took another five hours to bring the blaze under control. It was not until the 11th November, three weeks after the first outbreak of fire, that the brigade were able to leave the scene.

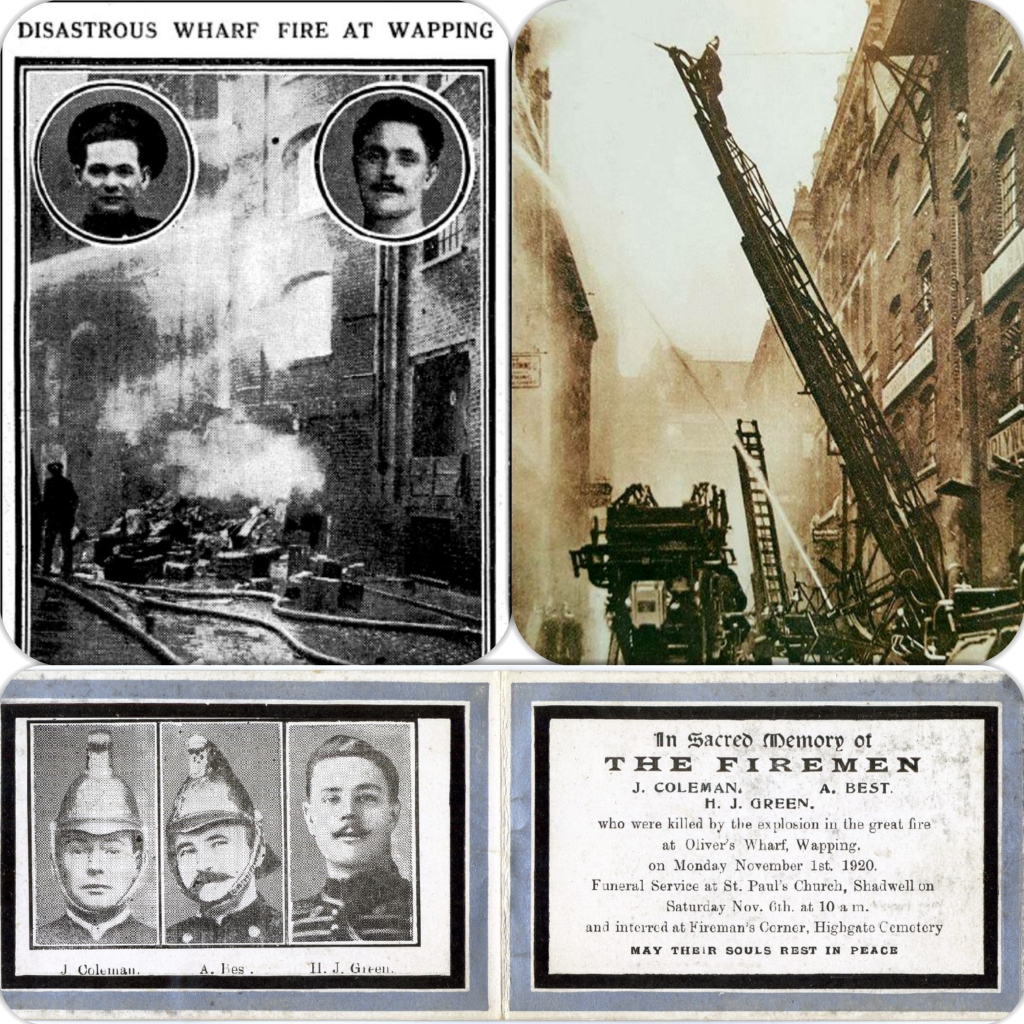

London’s major fires attracted large crowds. In many cases, thousands of spectator’s would flocked to watch the London Fire Brigade at work and the drama unfold. For the crews of East London’s Shadwell fire station it was the start of a new month, the month of November. For three of their number it was the last day that they would ever see. Like most of London’s firemen they had welcomed in the recent major changes to their working conditions. The LCC had finally agreed to introduce into the brigade two watches (shifts) and its firemen had now only to work a seventy-two hour week! That news had not made much impact on the daily London newspaper scene, but the mens’ demise would, as the following day newspapers proved, record banner headlines: ‘London Fire Tragedy’ and ‘Disastrous Wharf fire at Wapping.’

Late on the evening on Sunday 1st November the fire engines at the former Metropolitan fire brigade stations of Shadwell, located in Glamis Road E1 (adjacent to the Shadwell Basin), and Whitechapel, at 27 Commercial Road turned out of their respective stations responding to a fire call at ‘Lower Oliver’s Wharf’ in Wapping. The Brigade’s nearest fire-float, the Beta II, prepared to leave her moorings at Cherry Garden Pier and proceed to the fire that they already had sight of on the north bank of the river which stood adjacent to the St Johns’ Wharf, less than a mile distant. Within minutes the motor-engines arrived and the fire was already of such proportions that it necessitated the urgent attendance of other fire station crews to tackle a rapidly developing fire situation.

Lower Oliver’s Wharf was built in the 1830s. The Victorian brick built riverside wharf was a wide four storey building in the narrow Wapping High Street. It was one of many such warehouses located in a mix of five and six storey building that lined the river frontage. The wharf stored untreated rubber and some of the firemen quickly pitch their wheeled escape ladder, whilst others used an extension ladder to gain access to the upper floors and from where their hoses might be directed. In the meantime others, under the direction of the Station Officer from Whitechapel, Station Officer Moore, entered the building to seek the seat of the fire. Within a very short time Moore detected the smell of escaping gas. He immediately instructed his men to withdraw.

Tragically, it was already too late for some. Even as the firemen were making their escape a tremendous explosion occurred. The firemen on the fire-float saw its devastating effects but where then unware of its fatal consequences. The sound of the explosion reverberated across the wide expanse of the Thames, a signal to the local population on both banks of the river that something dire had just happened. On the riverside, and the frontage on the narrow street, the windows shattered and cases of burning rubber shot out into the night

In the East London street fleeing firemen were caught in the blast, many being injured by the falling brickwork, iron shutters and other falling/flying debris. The escape ladder was tossed across the street together with the pitched extension ladder, hurled away from the wharf by the sheer force of the explosion, two of the firemen on the escape ladder being thrown to the ground.

Shadwell firemen John Coleman, Albert Best and Harry J. Green, who was a notable boxer and swimmer all received fatal injuries as a result of the explosion. District Officer Wood, who had arrived to take charge of the fire was caught in the blast and resultant collapse of part of the frontage of the building. He and six other firemen and officers, together with the dead, were removed to two nearby hospitals; the Wapping Infirmary and the London Hospital in Whitechapel.

In the immediate minutes following the explosion chaos reigned as firemen desperately fought to recover, and render assistance to, their fallen colleagues. Some only received relatively minor injuries whilst others suffered potentially life threatening wounds. For the three Shadwell firemen it was too late. As other firemen protected their comrades from the fire, salvagemen from the London Salvage Corps Whitechapel station rushed forward to assist in the rescue efforts.

With the Beta II fire-float now attacking the fire from the riverside, Chief Officer Arthur Dyer was heading to the scene of the catastrophe. He was only in his second year as London’s Chief Officer. He had joined the Brigade sixteen years earlier in 1904 as an officer entrant. By 1909 he had risen to the rank of District Officer. In those sixteen years 15 London firemen had been killed at operational incidents, but these were the first on his ‘watch’. In the months prior to his appointment as Chief seven London firemen had perished on the Albert Embankment. Dyer was very much a fireman’s officer, a man who led his men from the front. He was the recipient of the Brigade’s Distinguished Conduct Medal for his actions at a South London oil-shop fire, when the lives of two children were saved by his and another fireman’s actions. The other fireman was awarded the Silver Medal by the London County Council, the fireman’s equivalent of the VC. Now once again Dyer led the crews of forty motor pumps and pump escapes, plus three of his four fire-floats, in their attempts to quell the blaze. A blaze that had spread to the adjacent Lusk’s Wharf and involved a one-hundred ton barge, The Rippon, that had been laden with rubber.

Lower Oliver’s Wharf burnt to the ground. Lusk’s Wharf was gutted by fire and the barge, Rippon, sank. However, it was only by the combined efforts of both the land and river crews that the eleven other buildings that were involved were saved from more serious fire damage. The cost of the fire, in financial terms, was estimated to exceed £120,000.00. To London’s firemen that cost paled into insignificance when compared to the lives of their three lost colleagues.

Chief Dyer led the Brigades funeral honour guard as the bodies were carried on three of the brigade’s motor pumps. London’s firemen turned out in force to honour their dead. The coffins being borne by brass helmeted firemen passed the lines of land and river firemen as the three men were carried shoulder high into St Paul’s Church, Shadwell on Saturday 6th November. The bodies were later buried the same day at Firemen’s Corner in Highgate Cemetery, North London.

John Coleman was my great uncle. I knew he was killed attending a fire in East London, but until now I had never found any details. Thank you. Bob Davis

LikeLike