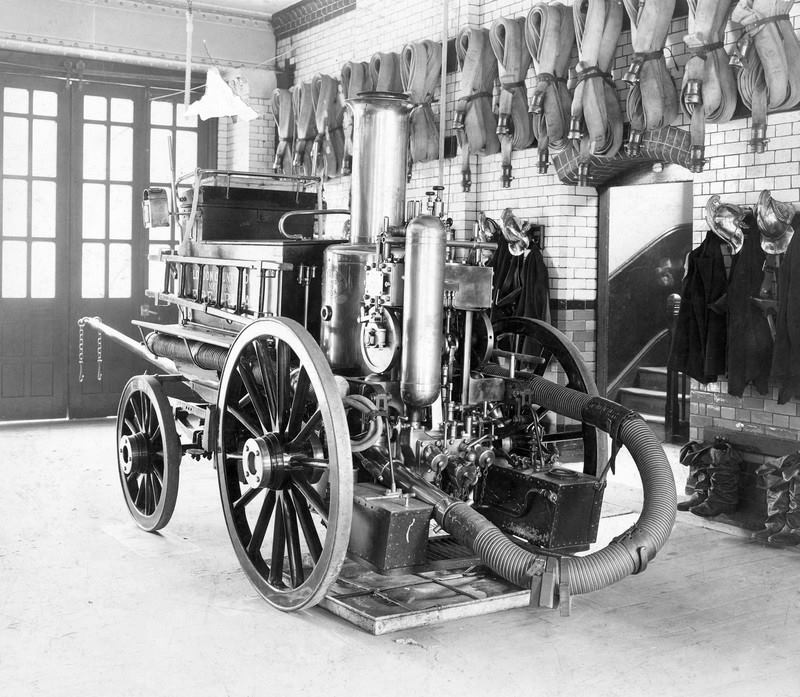

“We light our fires differently from everybody else,” says the fireman. “We put shavings on top, the wood next, and the coal at the bottom; then we strike a steam-match, and drop it down the funnel, and, behold the thing is done!” It was the engine fire of which the fireman spoke, and he was pointing to one of the magnificent steam fire-engines at the headquarters of the London Brigade.

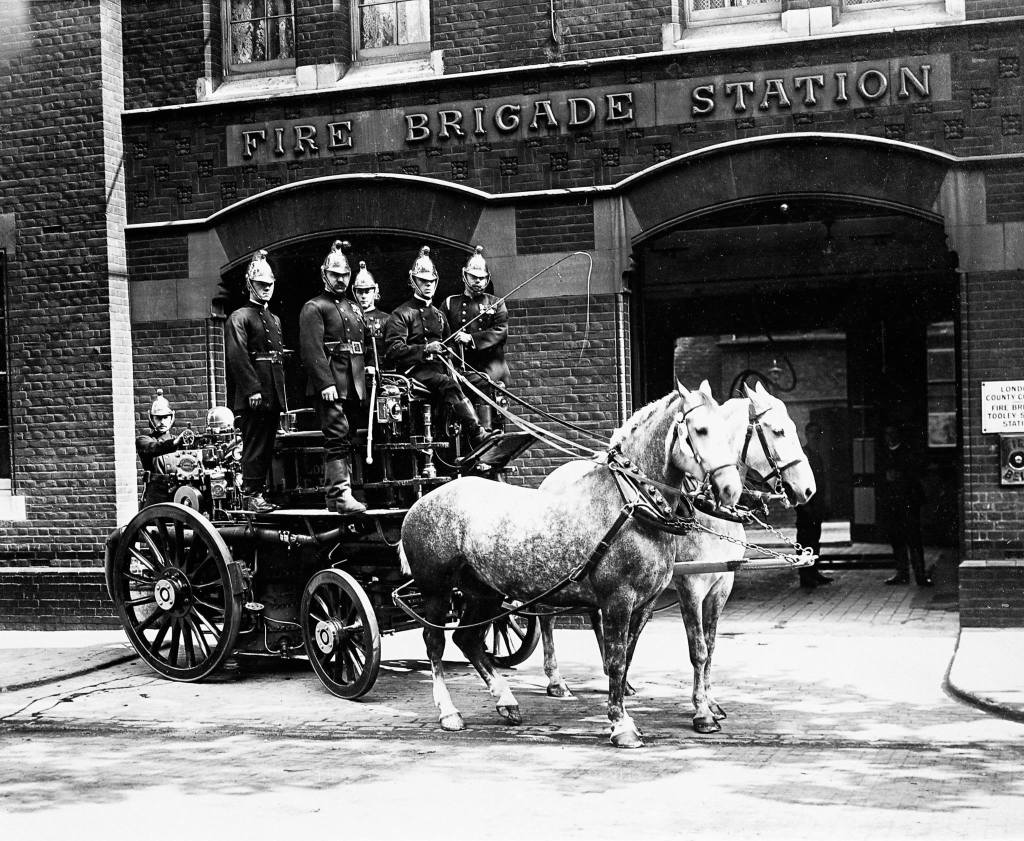

of No 1 station, Southwark at the Headquarters of the

Metropolitan Fire Brigade.

“Here is a steam-match,” he continued, “kept in readiness on the engine. It is like a very large fuse, and is specially made for us. Water won’t put it out.” He strikes the match, and it burns with a large flame. He plunges it into some water nearby, and it still continues to burn. It evidently means to flame until the engine fire is burning fast. The wood also is carefully prepared, being fine deal ends, specially cut to the required size; while the coal is Welsh—the best for engine-boilers. These details may seem trivial; but they assist in the rapid kindling of the engine fire, which is not trivial. But the rapid kindling of the fire is not the only reason why the brigade raises steam so quickly in its engines; in addition, a gas-jet is always kept burning by the boiler, and maintains the water at nearly boiling-point before the fire is lighted. This was a method adopted by Captain Shaw. But even this arrangement does not explain everything. To fully understand the mystery, we must leave this smart engine, shining in scarlet and flaming with brass, and go upstairs to the instruction-room for recruits.

If you could see a section of the engine fire-box and its boiler it would be very interesting and very ingenious. But probably a novice would ask, “Where is the boiler? I see little else but tubes.” That is the explanation. The tubes chiefly form the boiler; for they are full of water, and they communicate with a narrow space, or “jacket,” also full of water, and which reaches all-round the fire-box. This fire-box is held in a hollow below the tubes, which are placed in rows, one row across the other, just at the bottom of the funnel and above the fire-box. When, therefore, the flaming steam-match is dropped down the funnel, it finds its way straight down between the crossed mass of tubes to the shavings beneath; and the tubes full of the hot water are at once wrapped in heat from the newly-kindled and rapidly-burning fire. Every particle of heat and smoke and flame that rises must pass upward between the tubes. Furthermore, the hot water rises and the colder falls, so that there is a constant circulation maintained. The colder water is continually descending to the hottest tubes; and when bubbles of steam are formed, they rise with the hot water to the top. A space is reserved above the tubes, and around the funnel, called the “steam-space” or “steam-chest,” where the steam can be stored; the steam pressure at which the engine frequently works being a hundred and twenty pounds to the square inch. The result of all these ingenious arrangements is that, starting with very hot water, a hundred pounds of steam can be raised in five minutes.

“But,” it may be asked, “why is a fire not always kept burning, and steam constantly at high pressure?” The answer is that a constant fire, whether of coal or of oil, would cause soot or smoke to accumulate; while the Bunsen gas-burner affords as clear a heat as any, and maintains the water at a great heat, or even at boiling-point.

The nozzle of the hose belonging to one of the largest steam fire-engines measures 1¼ inch in diameter, some nozzles being as small as ¾ inch; and a large column of water is being constantly driven along the hose at a pressure of a hundred and ten pounds to the square inch, and forced through the narrow nozzle; here it spurts out, in a large and powerful stream, to a distance of over a hundred feet. It is obvious, therefore, that the power exerted by the steam-driven force-pumps and air-chamber is very high; and although such an engine may be in some folks’ opinion only a force-pump, it is a force-pump of a very elaborate character; and not inexpensive, the average price being about £1,000.

Every steam fire-engine carries with it five hundred feet of hose. The hose is made in lengths of a hundred feet, costing about £7 a piece, without the connections. If you examine a length, you will find it made of stout canvas, and lined with india-rubber, the result being that, while it is very strong, it is yet very light. Miles of it are used in the service; and upstairs in the hose-room you will find a large stock kept in reserve. Every piece is tested before being accepted.

The greatest care is taken of the hose. When it is brought back, drenched and dripping, from a fire, it is cleaned and scrubbed, and then suspended in the hose-well to dry. The hose-well is a high space, like a glorified chimney-shaft, without the soot, where the great lengths of canvas pipe can be hung up to dry. They are, in fact, not used again until they are once more in the pink of perfection. The outside public see the fire-brigade and their appliances smartly at work at big fires, but little know of the numerous details of drill and of management which are instrumental in producing the brilliant and efficient service.

Look, for another instance, at the manuals’ wheels. You will find them fitted with broad, wavy-shaped iron tyres, which extend over the side of the wheel and prevent it from tripping or slipping over tramway-lines in the headlong rush through the streets. And should a horse fall as he is tearing to the fire, that swivel-bar, which you will find at the end of the harness-pole, can be quickly turned, and in a moment the fallen steed is unhooked and helped to his feet again.

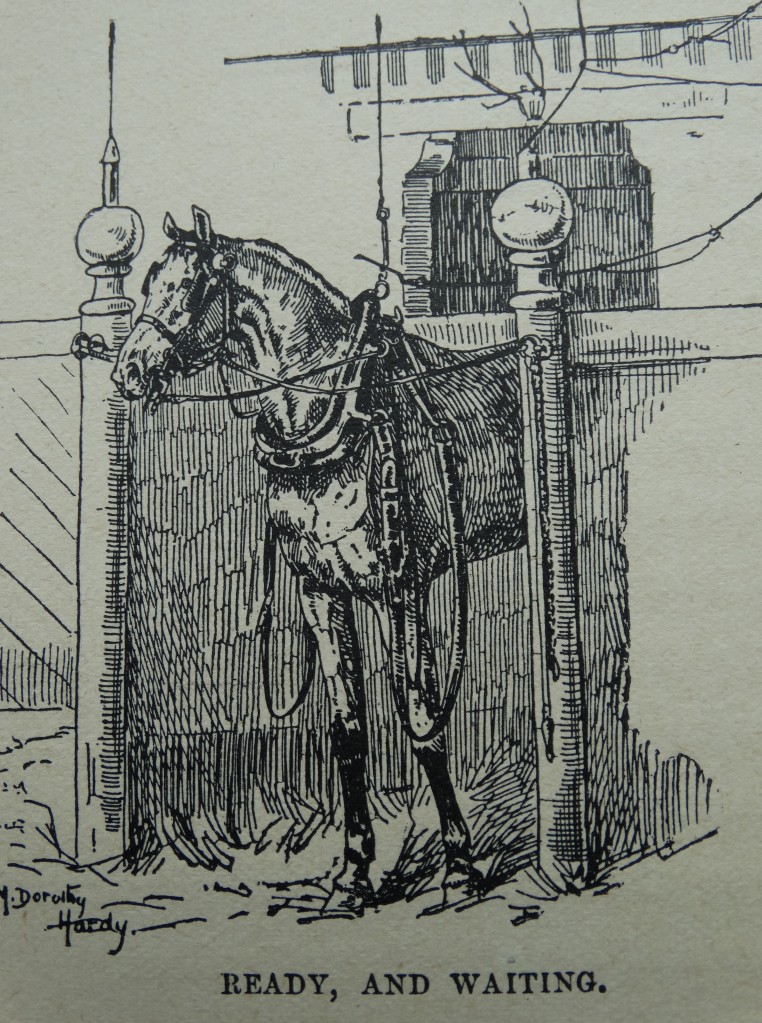

The horses are harnessed quite as quickly. Behind the engine-room and across a narrow yard you will find five pairs of horses, and, like the men, some are always on the watch. Here they stand, ready harnessed, their faces turned round, and looking over the strip of yard to the engines. The harness is light, but efficient; and the animal’s neck is relieved from the weight of the collar, as it is suspended from the roof.

Directly the fire-alarm clangs, the rope barring egress from the stall is un-swivelled, the suspender of the collar swept aside, and the horse, eager, excited, and impatiently pawing the ground, is led across the narrow strip of yard, hooked on to the engine, and is ready for his headlong rush through the streets. Horses stand thus ready harnessed at all stations where they may be kept; and when their watch is over, they are relieved by others, even though they may not have been called out to a fire. So intelligent have some of these animals become, that they have been wont to trot out themselves, and take their places by the engine-pole without human guidance; and so expert are the men and so docile the horses, that the whole operation of harnessing to the engine occupies less than a minute, sometimes, indeed, only about fifteen or twenty seconds. Every man knows exactly what to do, and has his place fixed on the engine. There is consequently no confusion and no overlapping of work.

A steam fire-engine has a “crew”—as the brigade call it—of one officer, one coachman, and four firemen. The officer No. 1 stands on the “near side” of the engine by the brake; No. 2 stands on the other side by the brake; No. 3 stands behind the officer, and No. 4 behind No. 2; No. 5 attends to the steam, and rides in the rear for that purpose; while the coachman handles the reins on the box.

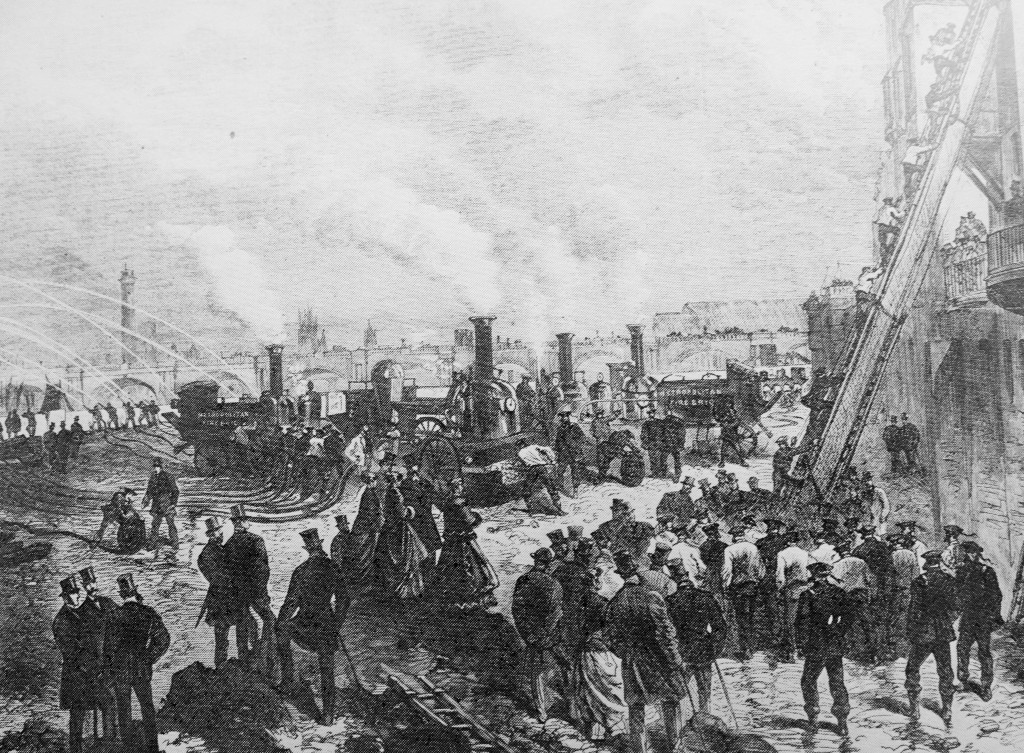

The positions are taken in a twinkling, the shed-doors open as swiftly, and away rush the impatient steeds, while the loud and exciting cry of “Fire! Fire!” rings from the firemen’s throats as they speed along. Wonderfully that cry clears the way through the crowded streets. When the men arrive at the scene of action, the preparations proceed in the same orderly manner. Nos. 1 and 2 brake the wheels, and proceed to the fire; while the coachman, if necessary, removes the horses, and is prepared to take back any message with them, No. 1 charging No. 2 to convey the message to the coachman. By the chief officer’s plan, however,—whereby a portable telephone, carried on a fire-engine, can be plugged into a fire-alarm post,—a message can be sent back from a fire by telephone instead of by a coachman. Meanwhile, No. 3 is opening the engine tool-box, and passing out the hydrant-shaft, hose, etc.; and No. 4 receives the hose, and connects it up with the water-mains, and places the dam or tank in which water is gathered from the hydrant. No. 3 is then busy with the delivery-hose, which is to pour the water on the flames; and No. 5 connects the suction-pipe. When ready, No. 4 hurries away with the “branch,” as the delivery-pipe with nozzle is called; No. 3 helping with the hose attached to it—until sufficient is paid out—and connecting the lengths as required. Then, when all is finished, everyone except the steam-man is ready to proceed to the fire, unless otherwise instructed. Every engine, it may be added, carries a turncock’s bar, useful for raising the cover from the hydrants.

So each one has his recognized duties in preparing the apparatus, all of which duties are duly set forth in the neat and concise little pocket drill-book prepared by Capt.Wells the Cheif Officer of the Metropolitan brigade. The most complete organization must be in operation, otherwise a force of a hundred or a hundred and fifty men, no matter how brave and zealous, gathered at one fire would only be too likely to get in one another’s way. And in a similar manner the crews of manual-engines and horsed escapes have all their duties assigned in preparing the machines.

Brigade’s six Superintendents standing at the rear.

(Wells was later Knighted and served in the Brigade, as its Chief, from 1896-1903.)

During a conflagration, the superintendent of the district in which the fire occurs controls the operations under the superior officers; for London is divided, for fire purposes, into five districts, which are known to the brigade by letters.

- A District is the West End, and the superintendent’s station is at Manchester Square;

- B District is the Central, and the superintendent’s station is at Clerkenwell;

- C District is the East and North-East, with district superintendent’s station at Whitechapel: all of these three being north of the Thames.

- The D District is the South-East of London, with superintendent’s station at New Cross; and the

- E District in the South-West, with superintendent’s station at Kennington.

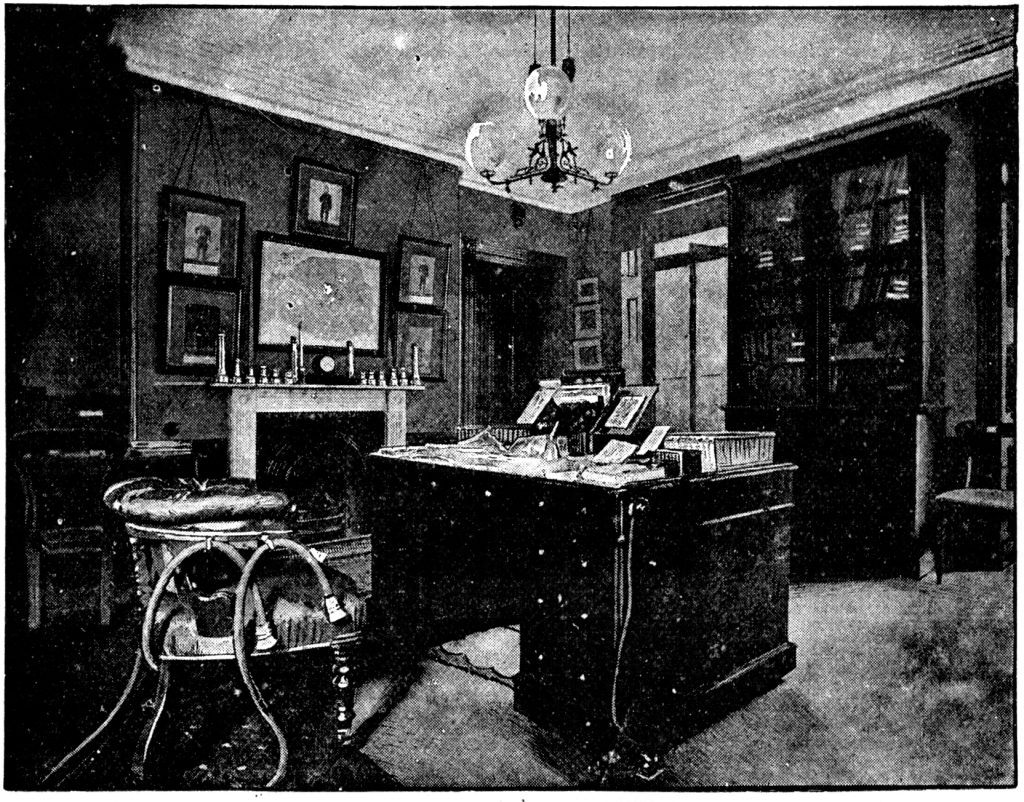

The headquarters, which are known as No. 1, and which used to be at Watling Street in the City, now occupy a central position in Southwark Bridge Road, and thence the chief officer can readily reach the scene of a fire.

All these stations are in electric communication, and all telegraph their doings to No. 1. The lines stretch from No. 1 to the five district superintendents’ stations; from there they extend to the ordinary stations in each district; and from these stations again they reach to points such as street stations, and even in some cases to hose-cart stations. The consequence is, that superintendents and superior officers can speedily arrive on the spot; and that, if necessary, a very large force can be concentrated at a serious outbreak in a short time. Thus headquarters knows exactly how the men are all engaged, and the character of the fire to which they may be called. Electric bells seem always clanging. Messages come clicking in as to the progress of extinguishing fires, or notifying fresh calls, or announcing the stoppage of a conflagration. And should an alarm clang at night, all the other bells are set a-ringing, so that no one can mistake what’s afoot.

Date: 1902

A list is compiled at headquarters of all these fires, the period of each list ranging from 6 a.m. to the same hour on the next morning. This list, with such details as can be supplied, is printed at once, and copies are in every insurance-office by about ten o’clock. The lists form, as it were, the log-book of the brigade. Some days the calls run up to seventeen or more, including false alarms; on other days they sink to a far fewer number; the average working out in 1898 to nearly ten calls daily. The Log also shows the causes of fires, so far as can be ascertained; and the upsetting of paraffin-lamps bulks largely as a frequent cause. The overheating of flues and the airing of linen also play their destructive part as causes of fires. The airing of linen is, indeed, an old offender. Evelyn writes in his Diary, under date January 19th, 1686: “This[night was burnt to the ground my Lord Montague’s palace in Bloomsbury, than which for painting and furniture there was nothing more glorious in England. This happened by the negligence of a servant airing, as they call it, some of the goods by the fire in a moist season; indeed, so wet and mild a winter had scarce been seen in man’s memory.” And now, more than two hundred years later, the same cause is prevalent.

Published in the Strand Magazine

But the upsetting and exploding of lamps is now, perhaps, the chief cause, especially for small fires; and more deaths occur at small fires than at large. This is not surprising, when we remember that such lamps are generally used in sitting or bedrooms, where persons might quickly be wrapped in flames or overwhelmed with smoke. Smoke, indeed, forms a great danger with which firemen themselves have to contend. At a fire in Agar Street, Strand, in November, 1892, a fireman was killed primarily through smoke. He was standing on a fire-escape, when a dense cloud burst forth and overpowered him. He lost his grasp, and, falling forty feet to the earth below, injured his head so severely that he died. Again, several men nearly lost their lives through smoke at a fire about the same time at the London Docks. The firemen were in the building, when thick smoke, pouring up from some burning sacks, nearly choked them. Ever ready of resource, the men quickly used some hose they had with them as life-lines, and slipped from the windows by means of the hose to the ground below.

Nevertheless, dense smoke is not the greatest danger with which firemen are threatened. Their greatest peril comes from falling girders and walls, from tottering pieces of masonry, and burning fragments of buildings, shattered and shaken by the fierce heat. Helmets may be seen in the museum at headquarters showing fearful blows and deep indentations from falling fragments of masonry, and firemen would probably tell you that they suffer more from this cause than any other. For small fires in rooms, little hand-pumps, kept in hose-carts, are most useful. They can be speedily brought to bear directly on the flames and prevent them from spreading. These little pumps can be taken anywhere; they are used with a bucket, which is kept full of water by assistants, who pour water into it from other buckets.

The fire, large or small, being extinguished, a message to that effect is sent to headquarters, and the firemen return, with the possible exception of one or two men to keep guard against a renewed outbreak. In the case of larger fires, perhaps half a dozen men and an engine will remain; while on returning, the various appliances have all to be prepared in readiness to answer another alarm. It sometimes happens that a fireman may be on duty for many hours at a stretch, or may only have time to snatch an hour’s sleep with clothes and boots on; for nearly every hour a fresh alarm comes clanging into the station, telling of a new fire in some part of busy London. And for any real need, there is, I trow, no grumbling or complaint from the brave men. But the miscreant detected in raising a malicious false alarm would have scant mercy. He would be promptly handed over to the police, and the magistrate would punish him severely—perhaps with a month’s imprisonment.

When not actually engaged at fires, the men find plenty to do in painting and repairing appliances, attending to horses, and keeping up everything to the pink of perfection. The hours on duty and for specified work are all marked down in the brigade-station routine, general work commencing at 7 a.m., and ending at one, while allowing for a “stand easy” of fifteen minutes at eleven. The testing of all fire-alarms once in every twenty-four hours, excepting Sundays and before six o’clock at night, also forms part of the brigade-station routine. Every fireman, however, has a spell of twenty-four hours entirely off duty in the fortnight; but at all other times he is ready to be called away. Indeed, men on leave are liable to be summoned in case of urgent necessity; but such time is made up to them afterwards.

Now, before being drafted into the effective ranks, all the men have to pass through a three months’ daily drill at headquarters. The buildings are very extensive, affording accommodation for about a hundred men, thirty-five or so being the recruits. In the centre, enclosed by the buildings, stretches a large square, in which the drill takes place. To see the combined drill is something like seeing the brigade actually at work; and this being Wednesday afternoon, and three o’clock striking, here come the squad of men marching steadily into the yard. The evolutions are about to begin.

How firemen recruits are trained.

Tramp, tramp, tramp! Three lines of wiry, muscular young men march into the centre of the yard.

“Halt! Right about face!”

Quick as thought the men pause and wheel around. Socket ladders over theit shoulders at the ready. The opening of the drill this afternoon is a course of exercises with these familiar appliances; but they soon give place to other evolutions, such as jumping in the sheet, practise with the engines, rescue by the fire-escape, and the chair-knot.

Every day some section of the drill is taken; but on Wednesday afternoons, the whole or combined drill is practised. All candidates must have been sailors; no one need apply who has not been at least four years an A.B. Further, they must be between the ages of twenty-one and thirty, and able to pull over the escape; that is, they must be able to pull up a fire-escape ladder from the ground by the levers. The height of the ladder is about 28 feet, and the pull is equal to a weight of about 244 pounds. It is a hard pull, and a severe test of a man’s strength; but after the first twelve feet, the weight seems lessened, as the man’s own weight assists him. In this test, as in some other things, it is the first step that costs. Should the candidate pass this test successfully, he is examined by the doctor; finally, he comes to headquarters for his probationary drills.

“Open order!”

The men break off from their exercises, and in obedience to instructions some of them run for large canvas sheets, and spread them out, partly folded on the ground. Then others calmly lie themselves down on these sheets. What is going to happen?

The recruits approach the recumbent figures, which lie there quite still, and apparently heavy as lead; the lifeless feet are placed close together, and the limp, inanimate arms arranged beside the body. Then, at a word or a sign, the bodies are picked up as easily as though they were tiny children, and carried over the recruits’ shoulders—each recruit with his man—some distance along the yard. The men are practising the art of taking up an unconscious person, overcome may be by smoke, or heat and flame, and carrying him in the most efficient manner possible out of danger.

There is more in this exercise than might at first appear. It might seem a comparatively easy task—if only you had sufficient strength—to throw a man over your shoulder and carry him thus, even leaving one of your hands and arms quite free; but you would find it not so easy in the midst of blinding flame and choking smoke; you would find it not so easy to pick your uncertain way through a burning building and over flaming floors, over a sloping roof or shaky parapet, and even down a fire-escape. Hence the urgent necessity that the fireman should be so well practised, that in a moment he can catch up an insensible, or even conscious person in exactly the most efficient manner, and, with hand and arm free, be able to find his way quickly out of the fire. He must be cool and clear-headed, dexterous, and sure-footed, ready of resource, and quick yet reliable in all his movements; and to these ends, as to others, the drill is directed.

But shouts of laughter are rising, as presently two or three of the recruits at the drill appear in a long flowing skirt, and look awkward enough in their unaccustomed garments as they stride along. They imitate women for the nonce, and are rescued in a similar manner, the men also carrying apparently lifeless figures down the ladders of the escapes.

The sheets, however, are used for other purposes of drill. See! A group of men are opening one out, and carrying it below an open window some twenty-five feet above the ground. There are fourteen or so of these men, and they grip the sheet firmly all round, and spread it out a little less than breast-high. A man appears at the window, twenty-five feet or so above. He is about to jump into the sheet far below. At the cry he leaps, or rather drops, down plump into the sheet; and the force of the fall is so great, that, unless these men were all leaning well backward, it would drag them toward the ground, and the rescued man sustain injury. As it is, they are all dragged pretty well forward by the impact of the fall.

A person jumping like this into a sheet should drop down into it, not spring, as though intending to cover a great space. And the persons holding the sheet should lean as far backward as possible. If they simply held the sheet, standing upright in the ordinary way, no matter how firm the grip, they would probably all be dragged to the ground in a heap.

The jumping-sheet is made of the best strong canvas about 9 feet square, and strengthened with strips of webbing fastened diagonally across. The sheet is also bound round at the edges with strong bolt-rope, and is furnished with about a score of hand-beckets, or loops. If at a fire all other means of rescue be unavailable, the sheet should be brought into use. Volunteers, if necessary, should be pressed into the service, and instructed to stretch out the sheet by the beckets, holding it about two feet or so from the ground. They should grasp the becket firmly with both hands, the arms being stretched at full length, their feet planted well forward, but their heads and bodies thrown as far back as possible. Even then the volunteers will probably find great difficulty in maintaining the sheet, and preventing it from dashing on the ground. If possible, a mattress or pile of straw or some soft object should be placed on the ground beneath the sheet. The uninitiated have no idea of the weight of a body suddenly falling or jumping on to the sheet from a great height, and this occasion is one for the putting forth of all the strength of body and determination of will of which a man may be capable.

But, now the sheet is being folded, and men are appearing on the roofs of the buildings above. A new exercise is beginning. Rescue by rope is now to be practised, and long threads of rope begin to appear. Imagine yourself a fireman on the top of a burning house, with smoke and flame belching out of the windows below, and agonizing screams for help ringing in your ears. No fire-escape is near, or, if near, not available; for it sometimes happens that persons cannot be rescued by ladders, and the staircase is a mass of flames. What would you do?

It is then that the firemen use the chair-knot, or, speaking popularly, they try rescue by rope. Every engine carries excellent rope of tanned manilla, and the fireman carries a rope about his body. Quickly the ends of the rope are fastened to two points, one on either side of the window—to a chimney-stack, if possible; then, as sailors know how, by means of what is called a “tomfool’s knot,” loops and knots are made in the rope—one loop to be slung under the arms, and the other to support the knees, and together forming a sort of chair. Speedily the loops are adjusted round the person to be rescued, and then he is gradually lowered to the ground. A guiding-rope has been attached, and thrown to the men below, and is used by them to steady the person’s descent, to prevent him from bobbing hither and thither, or to draw him out of reach of the flame and smoke.

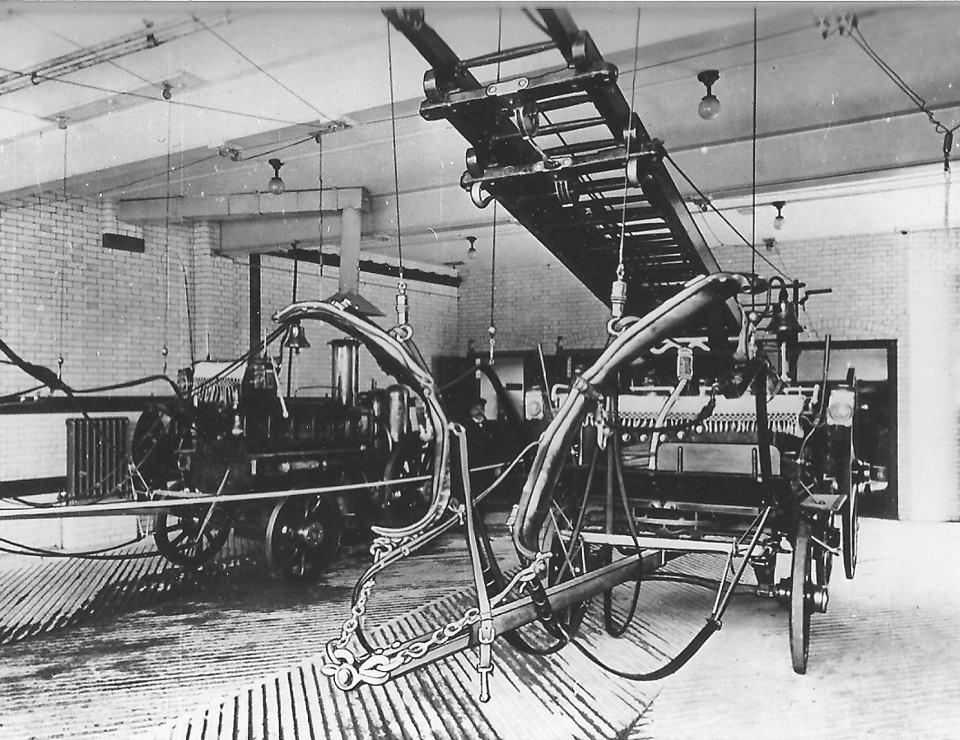

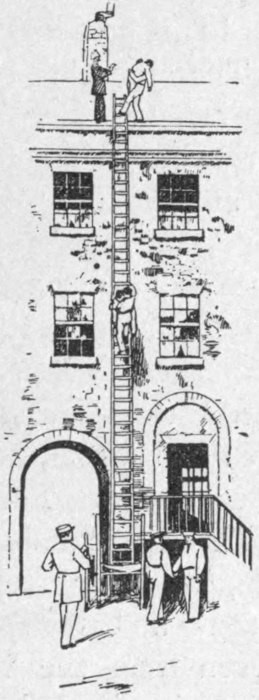

This exercise being over, there is a rattle and a clatter, and into the yard dashes a horsed fire-escape. The men pounce upon it at once, and in a trice whip it off its carriage and wheel it to the building. The present escapes are great improvements on the old forms, and two men can extend it with ease.

The first or main ladder of the escape reaches about 24 feet high; and in the 1897 pattern the 40-feet ladders having one extension. Other escapes have extending-ladders rising to a height of 50 feet, and even 70 feet, these being in three lengths. But an Act of Parliament now provides that all buildings above a certain height must have means of exit attached; this generally takes the form of iron ladders or stairways outside the building. All parts of an escape are as far as possible interchangeable, and the ladder-vans are designed to carry any ladders in the brigade.

And now the escape-drill is about to commence. The machine is placed against the building, which we must supposed to be burning. Up runs a fireman, with hands and feet on the rungs, to the window where the top of the ladder rests. If the window will not open readily, he may, in case of real need, smash it with his axe to obtain ready entrance. Then, if you watched him closely, you would see he did something which you would never think of doing. He fastens the end of his rope to the rung of his ladder, and, with the rest of the rope coiled over his arm, disappears into the room. The rope easily runs out as he moves, and affords him a means of speedily finding his way back to the window through the smoke; a very valuable arrangement it may prove to be, when the fireman finds an insensible person or a couple of children to rescue. One child he carries in his arm, and the other he throws across his shoulder, in the recognized brigade manner; and loaded thus, he gropes his way, guided by his one free hand, along the rope.

Or there may be more than one adult to save. Then the rescued person is carried over the shoulder to the top of the trough, or shoot of netting, with which some escapes used to be fitted at the back of the escape-ladder, and is slipped down it feet first to the firemen waiting below; while the plucky fireman above returns for the next person in peril. The fireman will probably follow the last down the shoot by turning a somersault and coming down head first; meantime, holding the other’s hands, and regulating the speed of the descent by pressing his knees and elbows against the sides of the netting. But without the shoot he descends by the ladder.

Should the fire occur at a house surrounded by garden-wall, shrubs, or forecourt, the machine is wheeled as close as possible, and the extension or additional ladders can be placed at a somewhat different angle from the first, so as to bridge over the intervening space and reach the farthest window. The ladders of fire-escapes may also be useful substitutes for water-towers. A water-tower is a huge pipe, running up beside the ladder, or tower; and as three or four steamers play into the base of the huge pipe, the water is forced up it, and the jet at the top can then be directed anywhere into the burning building.

“But we don’t want any water-towers,” exclaimed a fireman; “we can make one ourselves, if we need one.” That is, by using the fire-escape ladders to obtain points of vantage.

We soon see this accomplished. With a rush of horses and a whiz of steam, a fire-engine tears into the yard, the steam raising the safety-valve at a pressure of a hundred and twenty pounds to the square inch.

Off leap the men, as though actually at a fire; each attends to his prescribed duty; and ere long you see one of the men hurrying up the escape-ladder bearing the branch in his hand—i.e., the heavy nozzle end of the hose. In a second the engine whistles, there is a spurt of water, and the fireman directs the jet from the distant head of the ladder to a tank in the centre of the yard.

have been added to the Brigade’s fleet of horse drawn appliances.

The beckets on the hose, placed at intervals of seventeen and then twenty feet, over a hundred-feet length, are made of leather; and are most useful for fastening it to a chimney or any point of vantage by means of the fireman’s rope. The weight of a hundred-foot length when complete ranges from sixty to sixty-five pounds, and when full of water much more.

The hose for the London Brigade is woven seamless, of the best flax; and the interior india-rubber lining is afterwards introduced, and fastened by an adhesive solution. Unlined hose is used by some provincial brigades; and it is contended that the water passing through it keeps it wet, and therefore not liable to be burned by the great heat of the conflagration. On the other hand, the leakage is said to be a very objectionable defect. The internal diameter of the hose is two inches clear at the couplings, but a little larger within.

The steam-man is taught to remember the great power he rules; otherwise he may, by neglecting to give the warning whistle, endanger his brother-fireman’s life by suddenly sending the water rushing through the hose, or bringing a great strain upon it, when the men controlling it are not prepared. It may appear an easy thing to stand on a ladder or a house-top, and direct the jet on the fire; but it is not so easy to carry and to guide the long, heavy, and to some extent sinuous pipe, full of the heavy water throbbing and gushing through it at such tremendous pressure, especially when your foothold is none too secure. A fireman lost his life one night, when holding the hose on the parapet of a roof in the Greenwich Road. He overbalanced himself, and fell crashing, head downward, sixty feet or more below, and met a terrible death. Whether this fearful accident was entirely due to the heavy hose, we cannot say; but unless hose be laid straight, it is apt to struggle like a living thing. The reason is obvious. The water rushes through it at great pressure; and if the hose be not quite straight, the pressure on the bent part of the hose is so great that it struggles to straighten itself. Consequently, a fireman turning a stream will probably have to use a great deal of strength.

The increase in velocity of the water by the use of a branch and nozzle is, of course, very great. A branch-pipe is defined by Commander Wells as “the guiding-pipe from hose to nozzle.” Some branches are made of metal; but leather branches are being substituted for long metal pipes. Some of these latter measured from 4 to 6 feet long, and were not only very cumbersome to carry, but often impracticable to use with efficiency inside buildings.

Leather branch-pipes are sometimes longer, and are tapered from 2 inches in diameter to 1½ inch at the nozzle. When, therefore, a stream of water from two to two and a half inches in diameter, forced along at a great pressure, and distending the hose to its utmost capacity, is driven through the narrowing path of the branch-pipe, it spurts out from the nozzle at a much higher velocity; and it is just this narrowing part of the hose which the fireman has to handle, and whence he directs the jet. Some nozzles are like rose watering-can pipes, and are furnished with a hundred holes to distribute the water. These nozzles are useful in interior conflagrations and smoky rooms.

Yet, all important as is the engine-drill, and invaluable as are the engines for serious conflagrations, it is interesting to read in the Brigade Report that in 1897 no fewer than 808 fires were extinguished by buckets, and 460 by hand-pumps, while 98 were extinguished by engines, and, as we have said, 466 by hydrants and stand-pipes.

following a serious and fatal blaze in Queen Victoria Street in 1902.

The brigade bucket carried on the engine holds about 2½ gallons, and is made of canvas; it is collapsible, cane hoops being used for the top and bottom rings. Drill is maintained even for bucket and hand-pump; and the latter appliance is so portable, that the whole of the gear pertaining to it, including two ten-feet lengths of hose, is carried in a canvas bag.

Hand-pumps are often used for chimney fires. Two men usually attend, and expect to find a bucket in the house. They pour small quantities of water on the fire in the grate, and allow as large a quantity of steam as possible to pass up the flue. When the fire in the grate is quenched, the men use the hand-pump on the fire in the lower part of the chimney, and then, mounting to the roof, pour water down the chimney.

Taken at the Headquarters-Southwark. 1880s.

As sometimes the ends of wooden joists are built into the flues, an examination should be made to discover if the lead on the roof or in any place shows signs of unusual heat, and the joists have caught fire; for outbreaks of fire have been known to occur from this obscure cause. A comparatively simple but effective means of dealing with a chimney fire is to block up both ends of the chimney with thoroughly wet mats or sacks; while one of the easiest methods is to throw common salt on the fire. The heat decomposes the salt, and sets free chlorine gas—common salt being chloride of sodium, and chlorine being a gas which very feebly supports combustion, and tends to choke and dull a fire, if not to extinguish it entirely. And so the drill goes on, with scaling-ladders and long ladders, hose-carts and horsed escapes, steamers and manual-engines, the object of the whole being, not alone to perfect the men in their knowledge of the gear and machines, and skill in using them, but also to develop quickness of eye, and readiness and firmness of hand. A systematic routine is followed by fully-qualified instructors, part of the course being theoretical and part practical; while about the year 1898 a new syllabus of instruction came into use.

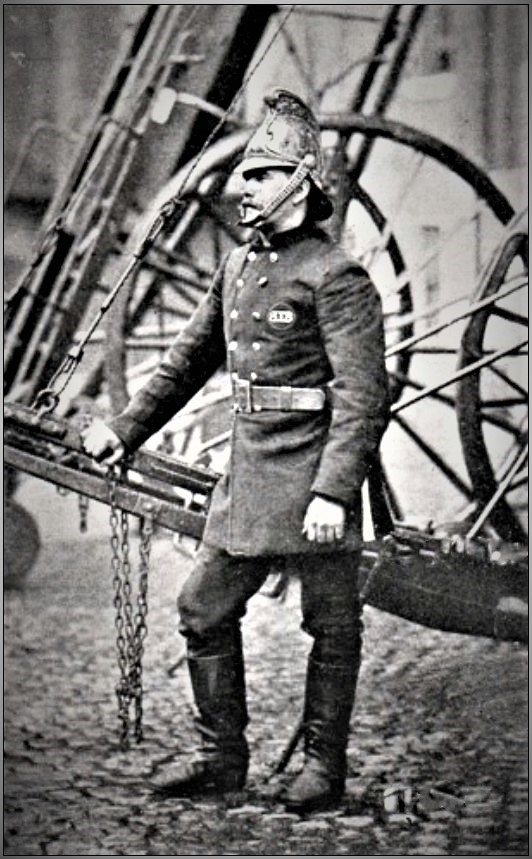

Among other alterations, it was arranged that a selected officer should take charge of the recruits’ drill for about two years, instead of engineers appointed at comparatively short intervals. Further, it was decided to permanently increase the authorized number of recruits, with the anticipation that never fewer than thirty men will be under instruction; and to prohibit them, if possible, from being called away to engage in cleaning or other work, so that their instruction drill should never be interrupted. When the men have passed through a three months’ course of instruction, they should be ready to be drafted into the ranks as fourth-class firemen. The men in the brigade are divided into four classes; in addition to which, there are coachmen, and licensed watermen for the river-craft, also engineers, foremen, and superintendents, the whole being in charge of a chief officer and a second and third officer.

First aid to the injured is also included in the instruction of the men; and the Recruits Instruction-Room and Museum contains a beautifully-jointed skeleton, kept respectfully in a case, for anatomical lessons.

Further, if you search the indispensable boxes on the engines, you will find among the mattocks and shovels, the saws and spanners and turncock’s tools, a few medical and surgical appliances. Every engine carries a pint of Carron oil, which is excellent for burns. Carron oil is so called from the Carron Ironworks, where it has long been used, and consists of equal parts of linseed oil and limewater; olive oil may be used, if linseed oil be not procurable. Carron oil may be used on rags or lint; and triangular and roller bandages are carried with the oil, also a packet of surgeon’s lint and a packet of cotton-wool. Accidents which are at all serious are, of course, taken as soon as possible to the hospital. But, alas! some accidents occur which no Carron oil can soothe, or hospital heal; and on that roll of honour in the little room beside the big engine-shed, and in the blackened bits of clothing and discoloured, dented helmets in the museum in the instruction-room, you find ample demonstration that a fireman’s life is often full of considerable risk.

Taken from the Strand magazine. 1880s.

These are the mute but touching memorials of the men who have died in the service; to each one belongs some heroic tale. Let us hear a few of these stories; let us endeavour to make these charred memorials speak, and tell us something of the brave deeds and thrilling tragedies connected with their silent but eloquent presence here.