(Watling Street was also the location of the Metropolitan Fire Brigade HQ from 1866-1878)

“Where is the fire?”

“City, sir; warehouses well alight.”

“Off, and away!”

The salvage corps horses are harnessed to the scarlet cart as quickly as though it were a fire-engine; the crew of ten men seize their helmets and axes from the wall beside the cart, and mount to their places with their officers; the coachman shakes the reins; and away dashes the salvage-corps trap to the scene of action.

The wheels are broad and strong. They do not skid or stick at trifles; the massy steel chains of the harness shine and glitter with burnishing, and might do credit to the Horse Artillery; the stout leather helmets and sturdy little hand-axes of the men look as fit for service as hand and mind can make them. Everything was in its right place; everything was ready for action; and at the word of command the men were on the spot, and fully equipped in a twinkling.

The call came from the fire-brigade. The brigade pass on all their calls to the salvage corps, and the chiefs of the corps have to use their discretion as to the force they shall send. The public do not as a rule summon the salvage corps. The public summon the fire-brigade, and away rush men and appliances to extinguish the flames and to save life. The primary duty of the salvage corps is to save goods. There is telephonic connection between the brigade and the corps, and the two bodies work together with the utmost cordiality.

We will suppose the present call has come from a big City fire. The chief has to decide at once upon his mode of action. No two fires are exactly alike, and saving goods from the flames is something like warfare with savages—you never know what is likely to happen; so he has to take in the circumstances of the case at a glance, and shape his course accordingly. Should the occasion require a stronger force, he sends back a message by the coachman of the cart; and in his evidence concerning the great Cripplegate fire, Major Charles J. Fox, the chief officer of the salvage corps, stated that he had seventy men at work at that memorable conflagration.

But see, here is the fire! Streams of water are being poured on to the flames, and the policemen have hard work to keep back the excited crowd. They give way for the scarlet cart, and the salvage men have arrived at the scene of action. Entrance may have to be forced to parts of the burning building, and doors and windows broken open for this purpose.

Crash! crash! The axes are at work. And a minute more the men step within amid the smoke. The firemen may be at work on another floor, and the water to quench the fire may be pouring downstairs in a stream. The noises are often extraordinary. There is not only the rush and roar of the flames, the splashing and gurgling of the water, but the falling of goods, furniture, and may be even parts of the structure itself. Walls, girders, ceilings may fall, ruins clatter about your ears, clouds of smoke suffocate you, tongues of flame scorch your face; but if you are a salvage man, in and out of the building you go, while with your brave brethren of the corps you spread out the strong rubber tarpaulins you have brought with you in your trap, and cover up such goods as you find, to preserve them from damage. Under these stout coverlets, heaps of commodities may lie quite safe from injury from water and smoke.

Overhead you still hear terrible noises. Safes and tanks tumble and clatter with dreadful din; part of the structure itself, or some heavy piece of furniture, falls to the ground; dense volumes of water poured into the windows rain through on to your devoted head. But you stick to your post, preserving such goods as you can in the manner that the chief may direct. May be you have to assist in conveying goods out of reach of the hungry fire, and your training has taught you how to handle efficiently certain classes of goods. Sometimes quantities of water collect in the basement, doing much damage; and down there, splash, splash, you go, to open drains, or find some means of setting the water free.

On occasion, the men of the salvage corps find themselves in desperate straits. At the Cripplegate fire, one of the corps discovered the staircase in flames, and his retreat quite cut off. With praiseworthy promptitude, he knotted some ladies’ mantles together into a rope, and by this means escaped from a second-story window to the road below.

On another occasion, Major Fox himself, the chief of the corps, was rather badly hurt on the hip, when making his way about a burning building at a fire in the Borough. The probability of accident is only too great, and it was no child’s play in training or in practice which enabled the corps to attain such proficiency as to carry off a handsome silver challenge cup at an International Fire Tournament at the Agricultural Hall in the summer of 1895.

The duties of the salvage corps do not end even when the fire is extinguished. They remain in possession of the premises until the fire-insurance claims are satisfactorily arranged. They do not, however, know which office is paying the particular claims, and all offices unite in supporting the corps. It is, in fact, their own institution, though established under Act of Parliament; and it is not, therefore, like the London Fire-Brigade, a municipal service.

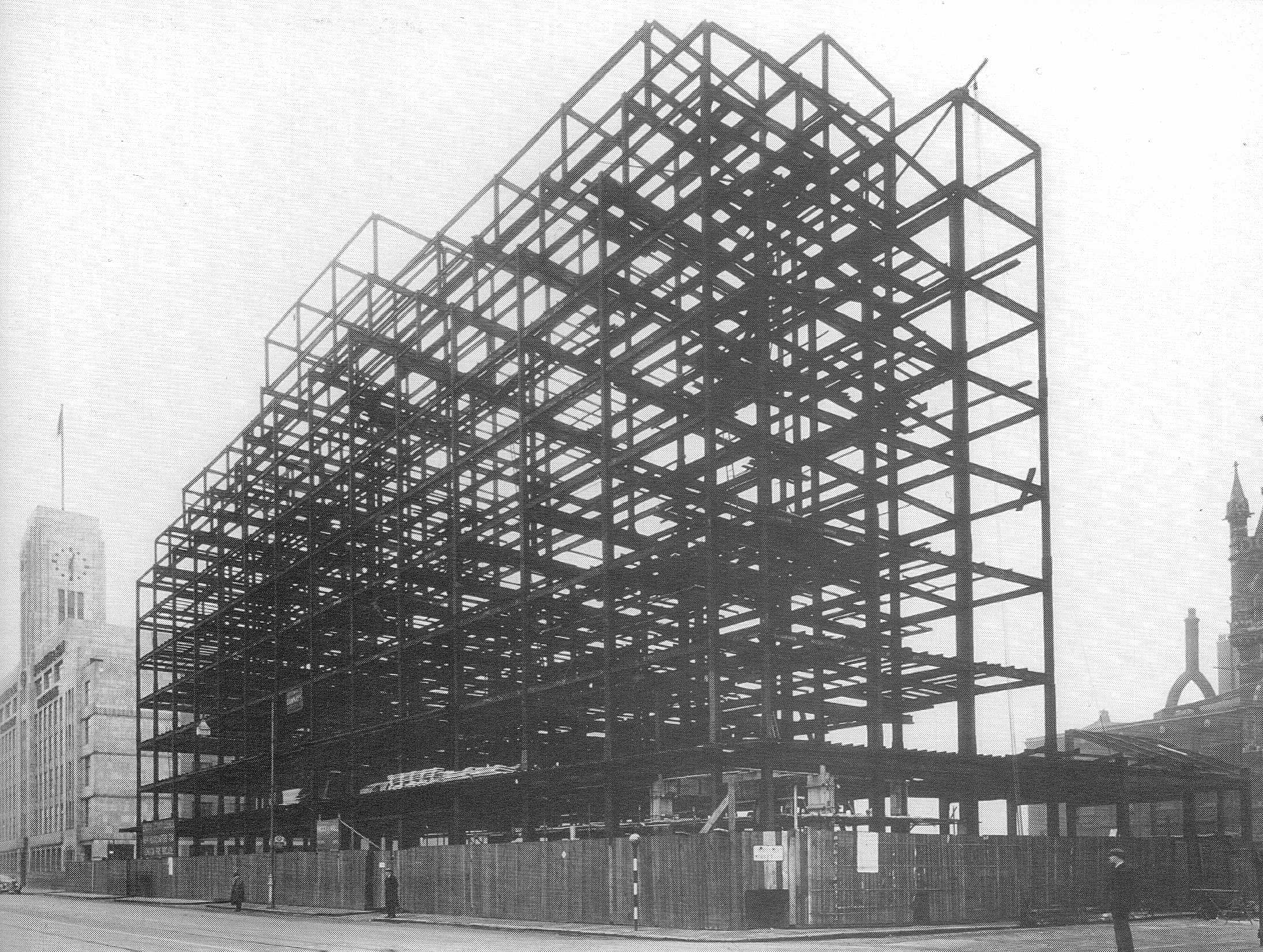

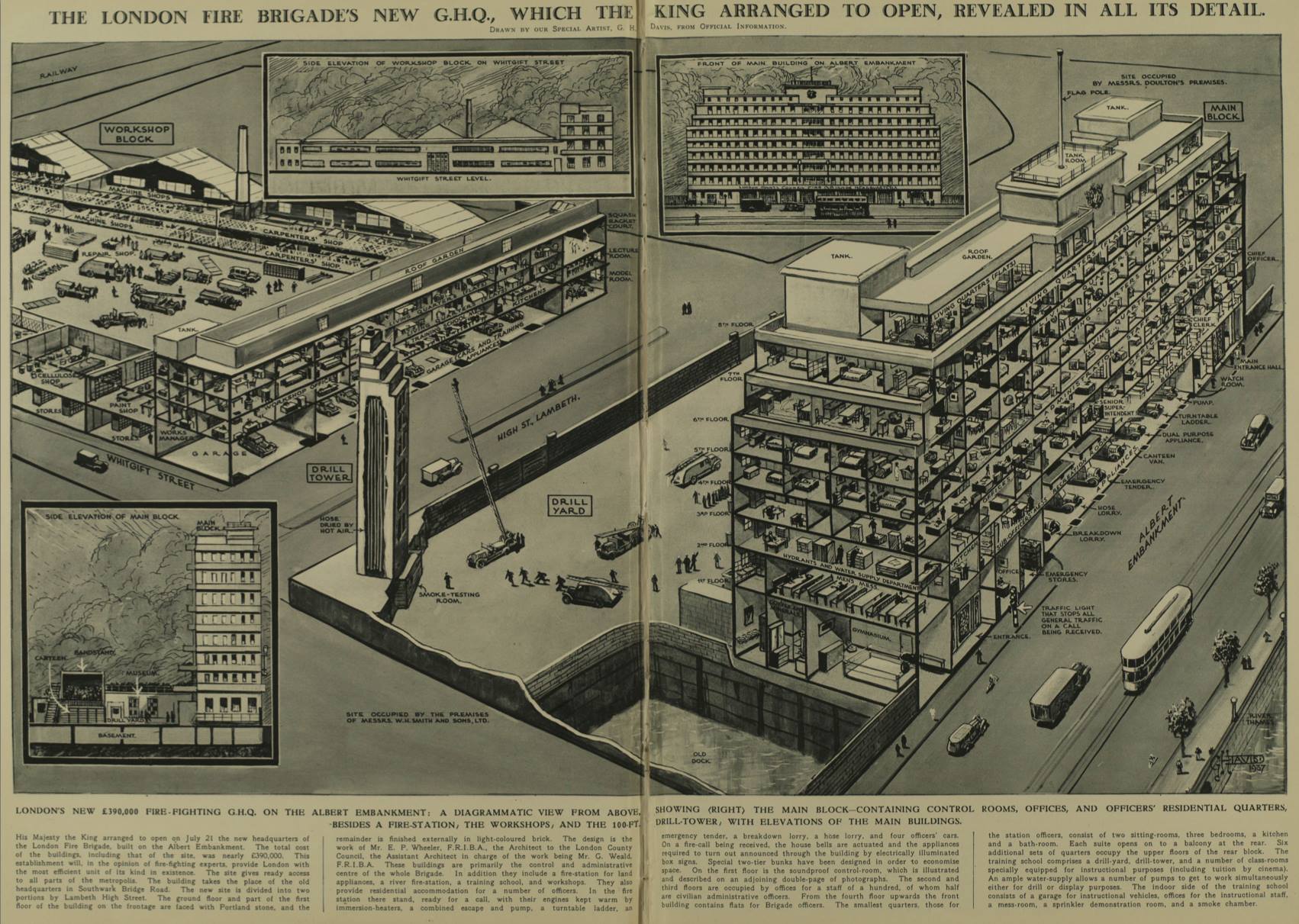

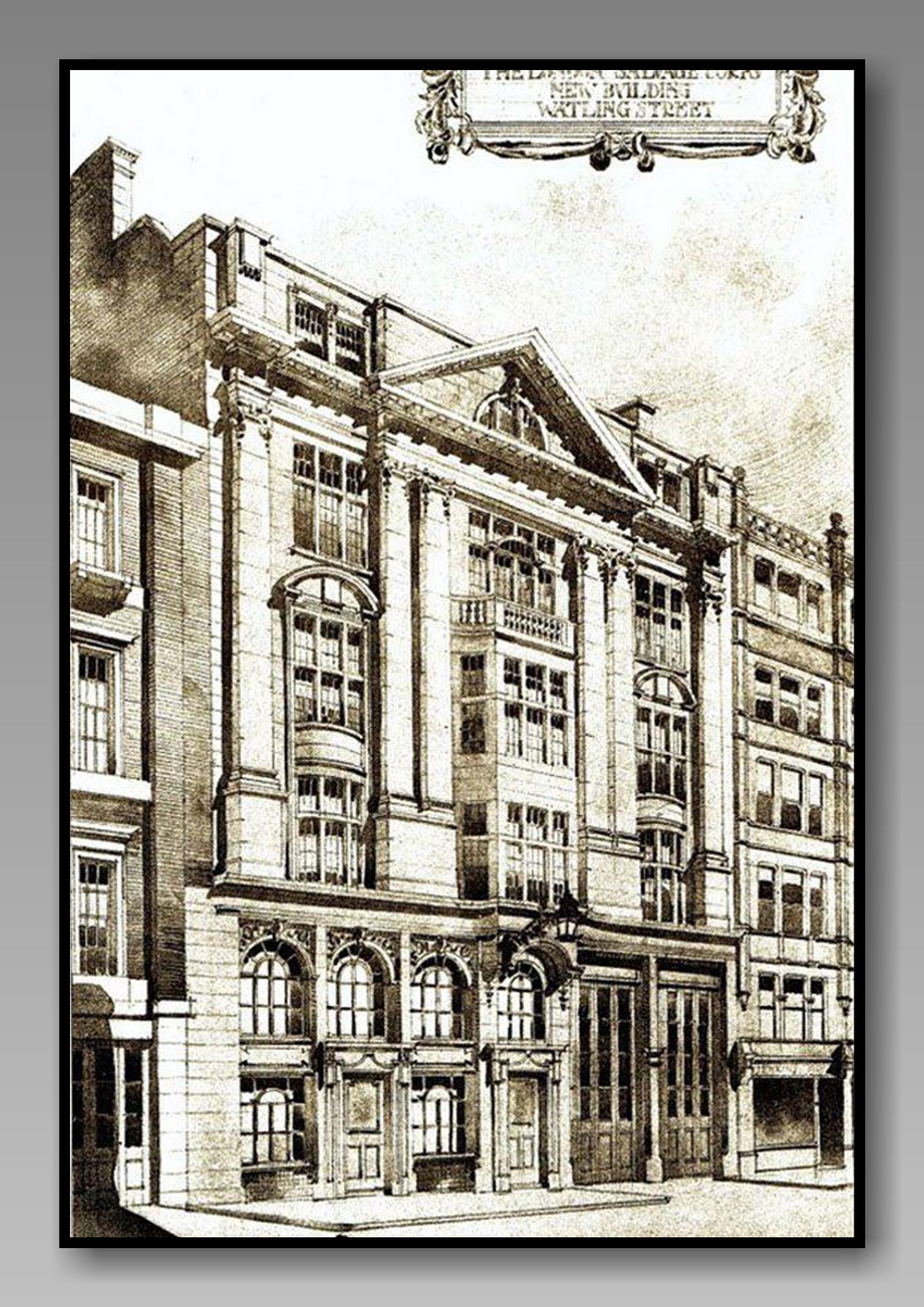

When the brigade was handed over to the Metropolitan Board of Works by the Act of 1865, provision was made for the establishment of a salvage corps, to be supported by the Fire-Insurance Companies, and to co-operate with the brigade. The corps has now five stations, the headquarters—where the chief officer, Major Fox, resides—being at Watling Street in the City. The eastern station is at Commercial Road, Whitechapel; the southern, at Southwark; the northern, at Islington; and the western, at Shaftesbury Avenue.

The force consists of about a hundred men. Their uniform somewhat resembles that of the fire-brigade, being of serviceable dark blue cloth, but with helmets of black leather instead of brass. They are nearly all ex-navy men, excepting the coachmen, some of whom have seen service in the army; indeed, candidates now come from the royal navy direct, but receive a special training for their duties, such as in the handling of certain classes of goods. Their ranks are divided into first, second, and third-class men, with coachmen, and foremen, five superintendents, and one chief officer.

Southwark Salvage Station and opposite the Brigade’s Headquarters station

in Southwark Bridge Road.

Their work lies largely outside the public eye. They labour, so to speak, under the fire; and it is difficult to estimate the immense quantity of goods they save from damage during the course of the year. Thousands of pounds’ worth were saved at the great Cripplegate fire alone in November, 1897. That huge conflagration, which was one of the largest in London since the Great Fire of 1666, may well serve to illustrate the work of the corps.

The alarm was raised shortly before one o’clock mid-day on November 19th, and an engine from Whitecross Street was speedily on the spot. As usual, the salvage corps received their call from the brigade; and in his evidence at the subsequent enquiry at the Guildhall, Major Fox stated he received the call at headquarters from the Watling Street fire-station, a warehouse being alight in Hamsell Street. He turned out the trap, and with the superintendent and ten men hurried to the fire. He also ordered other traps to be sent on from the other four stations of the corps, and left the station at two minutes past one. The Watling Street fire-engine had preceded him; and when he turned the corner of Jewin Street out of Aldersgate Street, he saw “a bright cone of fire with a sort of tufted top.” It was very bright, and he was struck by the absence of smoke. He thought the roof of one of the warehouses had gone, and the flames had got through. Perceiving the fire was likely to be a big affair, he at once started a coachman back to Watling Street with the expressive instructions to “send everything.”

The coachman returned at thirteen minutes past one, so the chief and his party must have arrived at the fire about five minutes past one; that is, they reached the scene of action in three minutes. The major and superintendent walked down Hamsell Street, and found upper floors “well alight,” and the fire burning downward as well. It was, in fact, very fierce; so fierce, indeed, that he remarked to his companion what a late call they had received. The firemen were getting to work, and he himself proceeded with his salvage operations.

Believing that some of the buildings were irrevocably doomed, he did not send his men into these, for the sufficient reason that he could not see how he could get the men out again; but they got to work in other buildings in Hamsell Street and Well Street, though the fire was spreading very rapidly. Many windows were open, which was a material source of danger, causing, of course, a draught for the fire. They shut some of the windows, and removed piles of goods from the glass, so that the buildings might resist the flames as long as possible. Eventually, the staff of men, now increased to seventy in number, cleared out a large quantity of goods, and stacked them on a piece of vacant ground near Australian Avenue. In spite of the heat and smoke and flame, in spite of falling tanks and safes and walls, the men worked splendidly, and were able to save an immense quantity of property.

Meantime, the firemen had been working hard. On arrival, they found the fire spreading with remarkable rapidity, and the telephone summoned more and more assistance. Commander Wells was at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital examining the fire appliances when he was informed of the outbreak. He left at once, and reached Jewin Street about a quarter past one. Superintendent Dowell was with him; and on entering the street, they could see from the smoke that the fire was large, and that both Hamsell Street and Well Street were impassable, as flames even then were leaping across both the streets.

Steamers, escapes, and manuals hurried up from all quarters, until about fifty steamers were playing on the flames. Early in the afternoon, the girls employed in a mantle warehouse hastened to the roof in great excitement, and escaped by an adjoining building. A staff of men soon arrived from the Gas Company’s offices; but the falls of ruins were already so numerous and so dangerous, that they were not able to work effectually. In fact, the whole of Hamsell Street was before long in flames; and in spite of all efforts, the fire spread to Redcross Street, Jewin Crescent, Jewin Street, and Well Street. The brigade had arrived with their usual promptitude; but before their appliances could bring any considerable power to bear, the conflagration was extending fast and fiercely.

The thoroughfares were narrow, the buildings high, and the contents of a very inflammable nature, such as stationery, fancy goods, celluloid articles (celluloid being one of the most inflammable substances known), feathers, silks, etc., while a strong breeze wafted burning fragments hither and thither. Windows soon cracked and broke, the fire itself thus creating or increasing the draught; the iron girders yielded to the intense heat, the interiors collapsed, and the flames raged triumphantly.

In Jewin Crescent, the firemen worked nearly knee-deep in water, and again and again ruined portions of masonry crashed into the roadway. Through the afternoon, engines continued to hurry up, until at five o’clock the maximum number of about fifty was reached. The end of Jewin Street resembled an immense furnace, while the bare walls of the premises already burnt out stood gaunt and empty behind, and portions of their masonry continued to fall.

Firemen were posted on surrounding roofs and on fire-escape ladders, pouring immense quantities of water on the fire, while others were working hard to prevent the flames from spreading. All around, thousands of spectators were massed, pressing as near as they could. They responded readily, however, to the efforts of the police, and order was well maintained.

This was the critical period of the fire. It still seemed spreading; in fact, it appeared as though there were half a dozen outbreaks at once. But after six, the efforts of the firemen were successful in preventing it from spreading farther. As darkness fell, huge flames seemed to spurt upward from the earth, presenting a strikingly weird appearance; they were caused by the burning gas which the workmen had not been able to cut off. Crash succeeded crash every few minutes, as tons of masonry fell; while in Well Street, at one period a huge warehouse, towering high, seemed wrapped in immense flame from basement to roof.

An accident occurred by Bradford Avenue. Some firemen, throwing water on the raging fire, were suddenly surprised by a terrible outburst from beneath them, and it was seen that the floors below were in flames. To the excited spectators it seemed for a moment as though the men must perish; but a fire-escape was pitched for them, and amid tremendous cheering the scorched and half-suffocated men slid down it in safety.

Cripplegate Church, too, suffered a narrow escape, even as it did in the Great Fire of 1666. On both occasions, sparks set fire to the roof, the oak rafters on this occasion being ignited. But the special efforts made by the firemen to save it were happily crowned by success, though it sustained some damage. Also Mr. Nein, one of the churchwardens, assisted by Mr. Morvell and Mr. Capper, posted on the roof, worked hard with buckets to quench the flames.

It was late at night before the official “stop” message was circulated, and eight o’clock next morning before the last engine left. It was found that the area affected by the fire covered four and a half acres, two and a half being burnt out; and no fewer than a hundred and six premises were involved. Fifty-six buildings were absolutely destroyed, and fifty others burnt out or damaged. Seventeen streets were affected; but happily no lives were lost, though several firemen were burnt somewhat severely. The total loss was estimated at two millions sterling, the insurance loss being put at about half that amount. The verdict, on the termination of the enquiry at the Guildhall on January 12th, 1898, attributed the conflagration to the wilful ignition of goods by someone unknown.

The quantity of water used at this fire was enormous. Mr. Ernest Collins, engineer to the New River Water Company, in whose district the conflagration took place, said that, up to the time when the “stop” message was received, the total reached to about five million gallons. No wonder that the firemen were working knee-deep in Jewin Street. The five million gallons would, he testified, give a depth of about five feet over the whole area. But, further, a large quantity was used for a week or so afterwards, until the conflagration was completely subdued. In addition to the engines, it must be remembered that there were fifty hydrants in the neighbourhood.

These hydrants can, of course, be brought into use without the turncock; but, as a matter of fact, that official arrived at two minutes past one, the same time as the first engine; while the fire was dated in the company’s return as only breaking out at four minutes to one, and the brigade report their call at two minutes to one.

The water used came from the company’s reservoir in Claremont Square, Islington. But this receptacle only holds three and a half million gallons when full. It is, however, connected with another reservoir at Highgate having a capacity of fifteen million gallons, and with yet another at Crouch Hill having when full twelve million gallons. As a matter of fact, these two reservoirs held twenty-five million gallons between them on the day of the fire, and both were brought into requisition, as well as the Islington reservoir. The drain was, however, enormous.

In the course of the first hour, the water in the Islington reservoir actually fell four feet. It never fell lower, however; for instructions were telegraphed to the authorities at other reservoirs to send on more water, and the supply was satisfactorily maintained,—a striking contrast, indeed, to the Great Fire of 1666, when the New River water-pipes were dry!

It was about nine o’clock when the chief officer of the salvage corps felt able to leave. During the eight hours he had been on duty, his men had saved goods to the value of many thousands of pounds. He had known to some extent the class of goods he would meet with, for the inspectors of the corps make reports from time to time as to the commodities stored in various City warehouses, and he is therefore to some extent prepared. On the following day, the 20th, the corps were occupied in pulling down the tottering walls of the burned-out warehouses which were in a dangerous condition.

(Taken from; The Project Gutenberg EBook of Firemen and their Exploits: