Few national organisations have been stood down twice-but the Auxiliary Fire Service (AFS) holds such a dubious honour. The first time was in 1941, with creation of the National Fire Service (NFS). Then on the 31st March 1968 it was ordered to stand-down again after 20 years of peace time activity. This time it was final. The men and women of the AFS rode into fire service history.

Its origins came about in the 1930s when the likelihood of a Second World War was already being planned for in Britain. Although not widely publicised the then National Government, under Ramsey MacDonald, were considering what arrangements would be necessary to cope with enemy aerial attacks on its strategic population centres. The Home Office (then responsible for the Fire Service) held a series of seminars and secret planning meetings to deliver a strategy in the event of war and the subsequent fire attacks on the British mainland from the air. London was considered a particularly vulnerable target for such enemy action, not least because it was the nation’s seat of government and the City of London was crucial to the country’s financial and business interests.

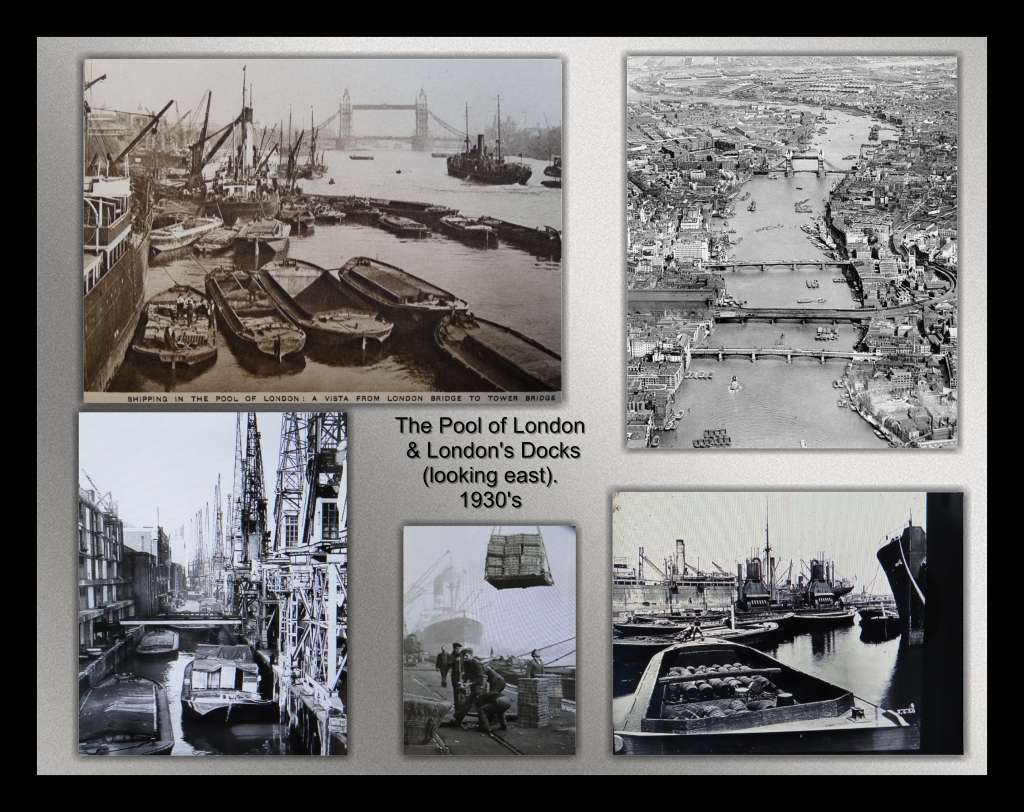

London in the 1930s looked vastly different to the London of today. The river Thames provided easy access for shipping to its vast network of extensive docks and associated warehouses. The dockland warehouses, starting from Southwark on the south bank and Blackfriars on the north bank ran eastward to the Essex and Kent borders. It was recognised, at an early stage, that it would require a massive expansion of the existing fire brigade(s) to deal with fires involving London’s central maze of narrow streets, warehouses filled with combustible products such as oils and grains and its dockyards with acres of stacked imported timber. Failure to respond to such a challenge could leave London little more than a smoking ruin.

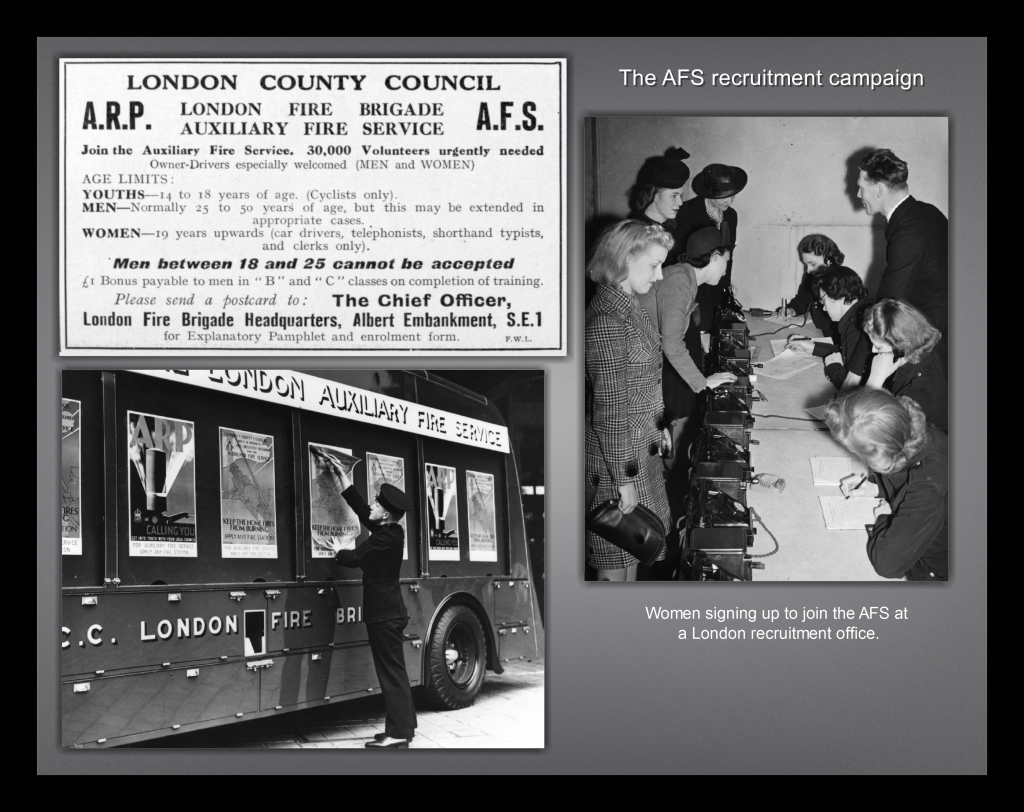

The AFS was formed on the 1st January 1938 and their numbers rapidly grew. A massive recruitment drive was launched. In London sixty London Fire Brigade (LFB) vehicles toured London’s streets alongside an AFS poster campaign and planes even flew the over capital trailing AFS recruitment banners. The Thames was also used to advertise this new fire force and the Brigade’s high-speed fireboat, the James Braidwood, flew similar banners seeking recruits to supplement the London Fire Brigade’s River service. The success of campaign attracted some 28,000 volunteers. Volunteers who would supplement the regular London Fire Brigade in event of war.

Picture credit-Daily Sketch.

This was a major logistical exercise for both the London County Council (LCC) and the LFB. Not least of the problems was the area we now know as Greater London. Prior to the outbreak of war in 1939 it had at least 66 fire brigades! This included the London Fire Brigade, the largest, which covered the whole of the former LCC’s administrative area. Some of these other brigades were one fire engine outfits: those that only protected a small borough area. Others had four or five stations such as West Ham and the Croydon brigades. Quickly various buildings, and vehicles, were seconded into service to house and equip this basically trained corps of AFS firemen and women that had now greatly expanded London’s fire service.

Garages, filling stations and schools, empty since the mass evacuation of children, were taken over and adapted as AFS fire stations. Some 2,000 London taxis were brought into service and used to tow trailer pumps. The London taxis were large enough to carry a small crew, hold a ladder on top and with the hose stored in the luggage compartment, plus pull a trailer pump. However, the accommodation was frequently poor at best. The new volunteer firefighters spent many hours making good their bases and even building their own wooden beds. In addition to this they erected brick walls over windows and sandbagged entrances to protect themselves from blast damage.

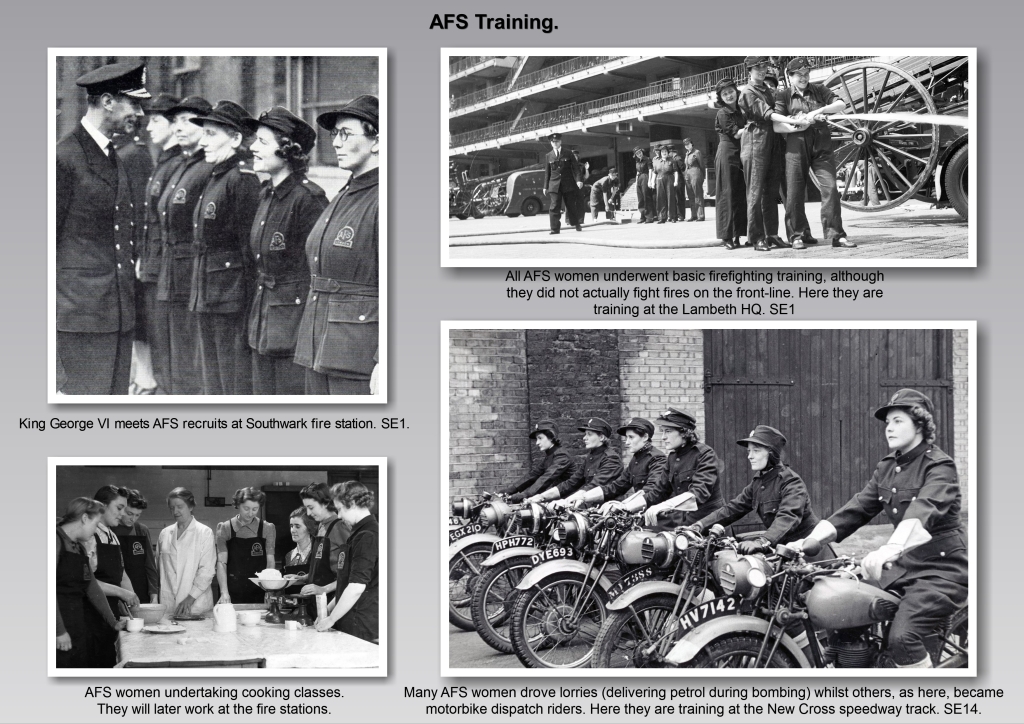

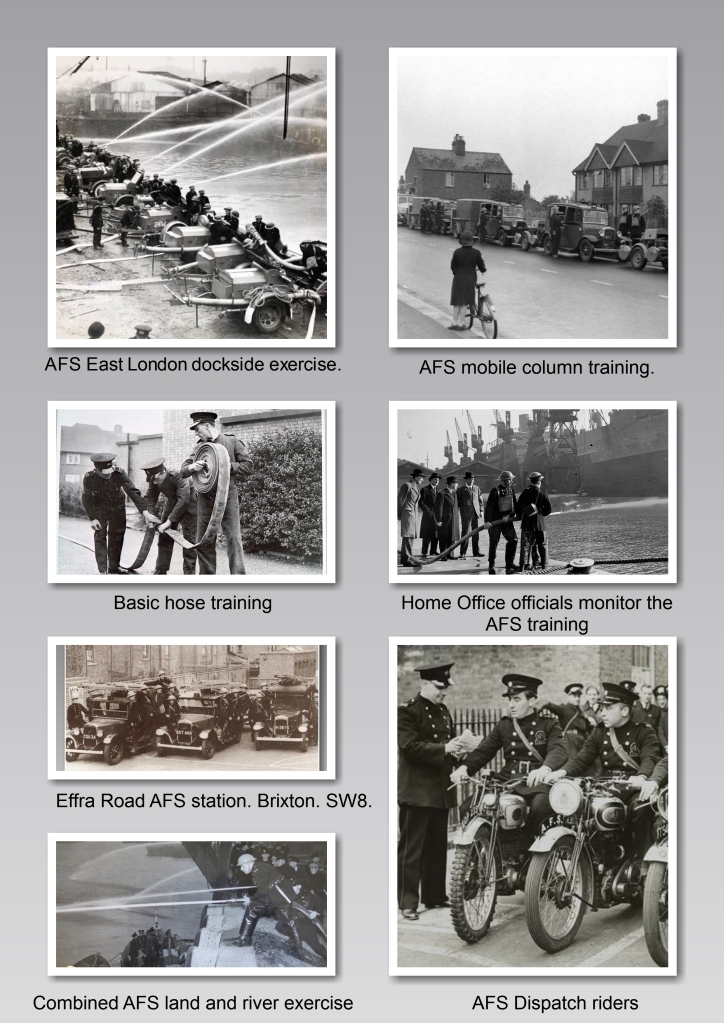

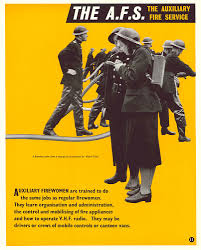

Basic training was provided by LFB firemen. Detached from normal firefighting duties, they put the new AFS recruits through 60 hours of practical and theoretical lessons. Whilst some women chose to undertake dispatch rider (motorcycle) messenger duties and others opted for motor driving, most were trained in ‘watchroom’ duties and the necessary procedures for mobilising fire engines and pumping units. Everyone underwent basic firefighter training. They were, of course, civilians. They had volunteered from every trade and profession, from every walk of London life. Office workers, labourers, lawyers, tailors, cooks, and cleaners they had taken up the call to join the AFS.

The AFS recruits were divided into different categories. This was based on their physical capabilities, their age, gender, and skills. Men considered Class B performed general firefighting duties. B1s worked only on ground level, either pump operating or driving. Others, recruited from trades on the Thames, were classed for River Service work and whilst women would be in the thick of it none performed actual frontline firefighting duties. (Although falling bombs did not discriminate those women delivering petrol to the firemen and those fighting the fires.) The youngsters, under 18 years of age, became messengers equipped with either motorcycles or pedal cycles. Those auxiliaries who became full-time firefighters on the outbreak of war received a weekly wage. Firemen earned £3 per week; women got £2. Those aged 17–18 received £1-5 shillings and the 16–17-year-olds got £1 a week.

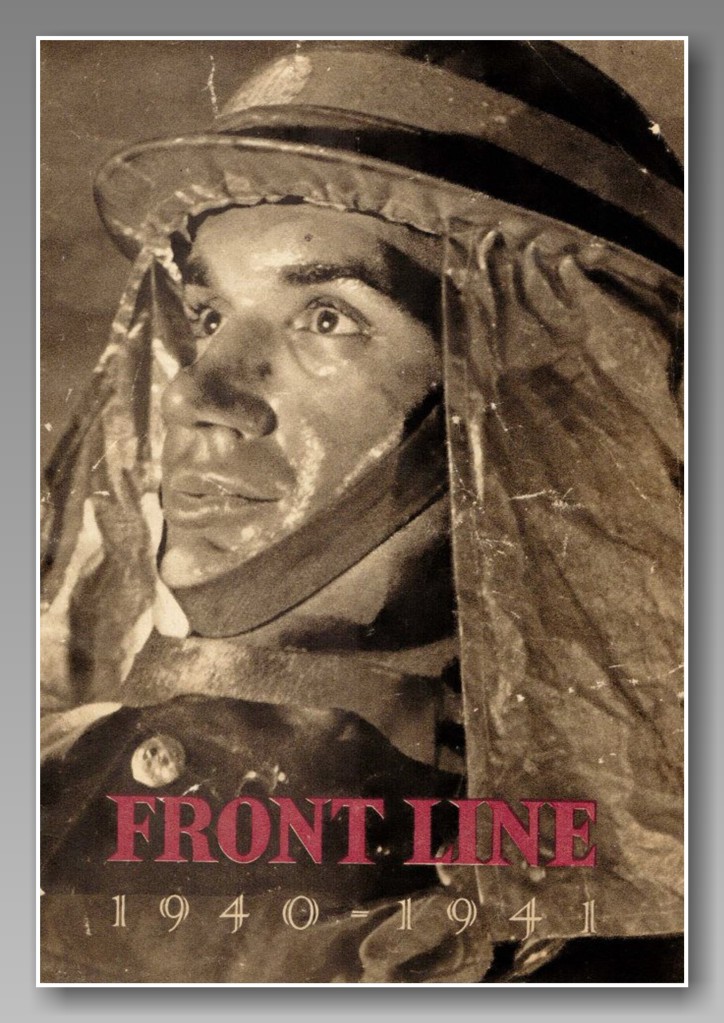

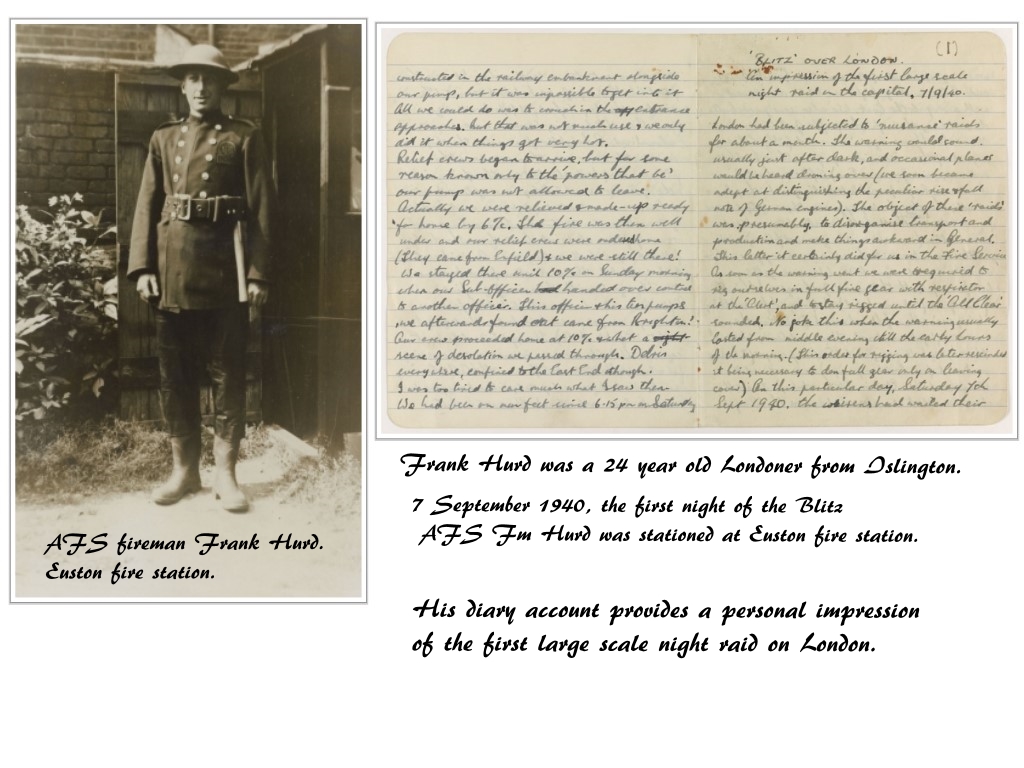

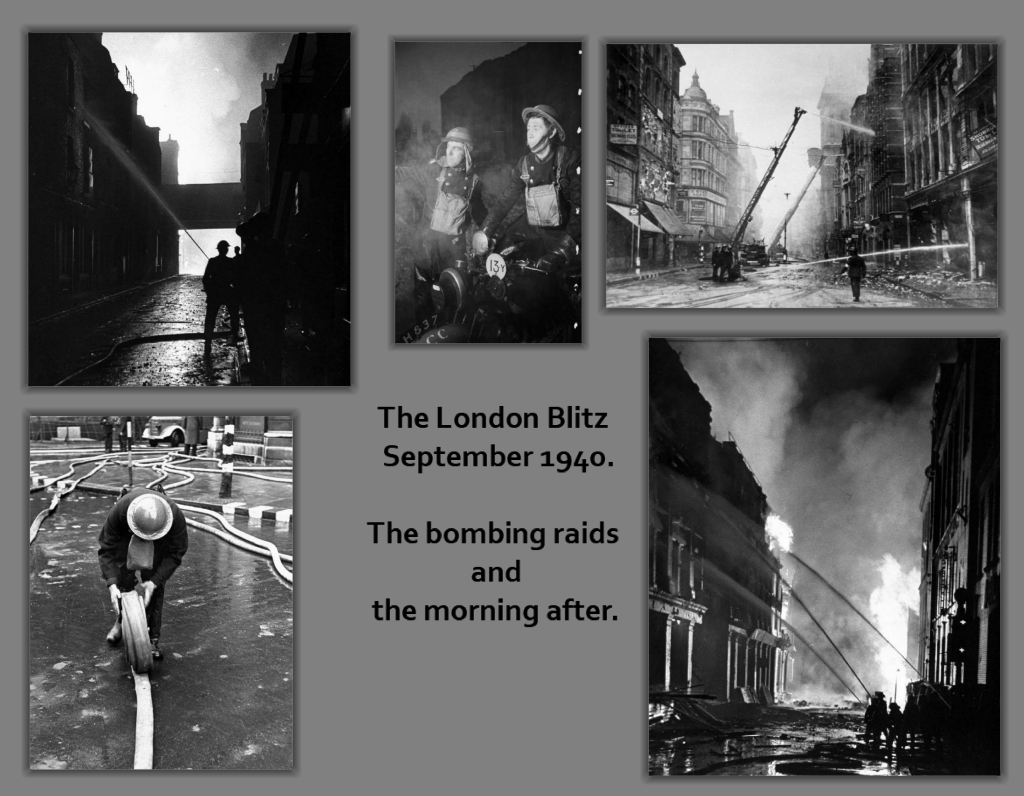

The AFS’s baptism of fire came on a 1940 September evening, the 7th. With basic training, and as yet untried, the auxiliaries were dispatched to the first big raids of the war. The official WWII publication Front Line 1940-41 recorded what happened that fateful night. “The auxiliaries, four-fifths of them with no prior experience of actual fire-fighting, faced the greatest incendiary attack ever launched…”

By midnight on the 7th there nine fires in London rating over 100 pumps. In the Surrey Docks were two of 300 pumps and the other 130 pumps. At Woolwich Arsenal the count was 200 pumps; at Bishopsgate Goods Yard another 100-pump fire. Such was the intensity of the enemy bombing that these fires all became conflagrations. The intensity of the radiated heat from the Surrey Docks blaze was such that the fire-float Massey Shaw, moored on the opposite bank (a distance of 300 yards) had her paint blistered! By the end of that first month 50 London fire-fighters had perished in action. 500 others were injured and many invalided out of the service. Almost overnight the previously lampooned and derided AFS were popular heroes. Many crews, returning from blazes, wet and exhausted were cheered by passers-by in the street.

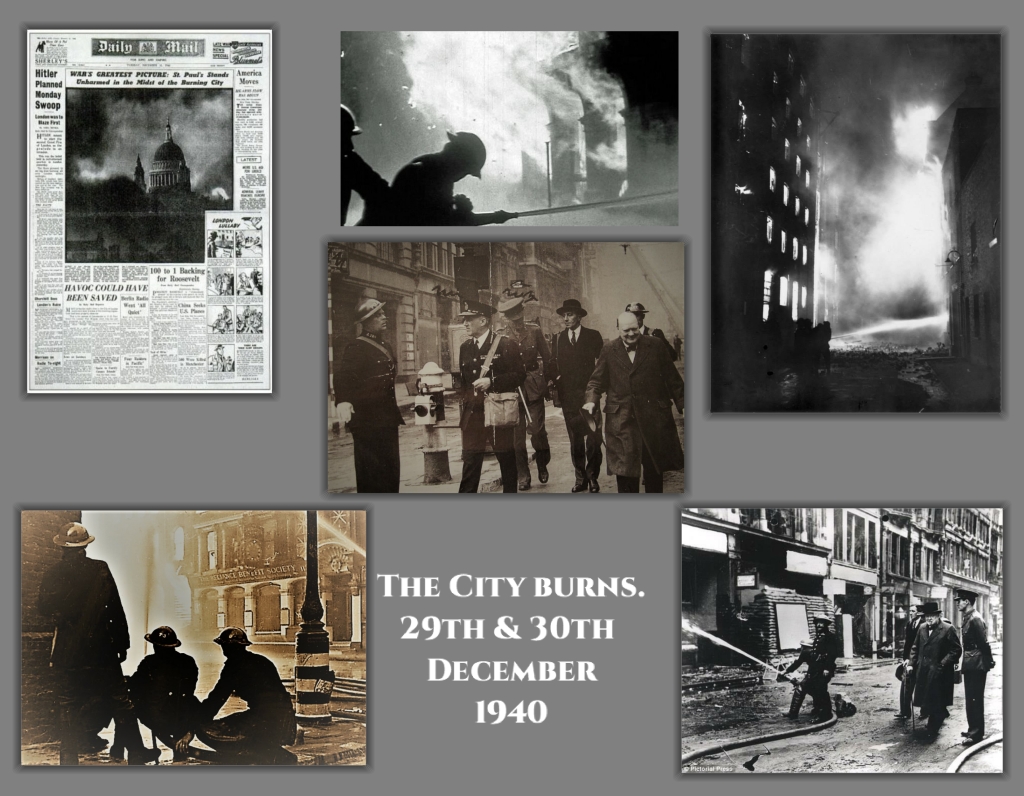

As the raids intensified in the following months the number of fires were measured in the 10s of 1000s. In December of 1940 bombing reached a climax with the concentrated bombing of the City of London. With the Thames already at a low tide, water supplies were cut off for a while the men and women of the AFS got on with their job. Their courage helped to save St Paul’s by using all kinds of improvised fire engines and hauling heavy trailer-pumps to provide water supplies whilst AFS women delivered petrol supplies, acted as dispatch rider messengers, and staffed the control rooms and station watchroom’s, all under enemy fire. Then in the new year (1941) with a widening of the enemy bombing campaign AFS conveys travelled to far flung cities, such as Coventry, Portsmouth, and Southampton, to provide much needed fire-fighting reinforcements.

AFS wartime heros.

AFS fireman Harry Errington. GC.

Harry Errington was born in Soho. After attending Westminster free school, Harry won a trade scholarship to train as an engraver his mother, fearful, the craft would adversely affect his health, Harry went to work for his uncle’s tailoring business instead. Now a master tailor. He was also a volunteer Auxiliary London fireman working in his beloved West End. Just before midnight on the 17th September 1940, together with other AFS men, he was in the basement of a three-storey garage in Soho. It was used as a private air raid shelter and rest area for the fire service personnel. A bomb hit and all three floors collapsed. The resultant explosion killed some 20 people, including six London firemen.

In the Supplement to the London Gazette (issue No 35239, on the 8th August 1941, pg. 4545.) it was announced; The KING has been graciously pleased to award the GEORGE CROSS to Auxiliary Fireman Harry ERRINGTON. He showed great bravery and endurance in effecting the rescues, at the risk of his own life.

Only three such awards were made to fireman during the Second World War; Harry was the only AFS London fireman so honoured. He received his GC from King George VI in October 1942.

AFS Firewoman Gillian Tanner. GM.

Gillian “Bobbie” Tanner delivered petrol to fire pumps in Bermondsey while the docks were being bombed during the Blitz in September 1940. On 3 September 1939, the day war broke out, 19-year-old Miss Tanner drove to London in her front-wheel drive BSA car from her home near Cirencester, in Gloucestershire, to see what she could do to help. The Women’s Voluntary Service directed her to the auxiliary fire service where she became a driver. This country girl, whose main past-time had been horse riding, was at first alarmed to hear she was being posted to Dockhead, Bermondsey, in south-east London. She recalled:

“There were two drivers allocated to Dockhead and I was the only one who had the heavy goods licence, so I had the canteen van and petrol lorry to drive,” she said. “You had the petrol in two-gallon tins and they were stacked on shelves around the lorry. I didn’t think about it at the time, luckily.”

“They took over a lot of schools and made them sub stations and they all had their own trailer pumps – I remember going to one not far from Tower Bridge and we were pouring petrol into the engine and it was red hot. I didn’t even think about the fact that one drop, and we would go up in smoke. You had a job to do and you got on and did it.”

Her citation read:

Awarded the GEORGE MEDAL. (L/G, 35058, 31st Jan 1941, pp. 610.)

Firewoman (Aux) Gillian Kluane TANNER. Six serious fires were in progress and for three hours Auxiliary Tanner drove a 30-cwt. lorry loaded with 150 gallons of petrol in cans from fire-to-fire replenishing petrol supplies.

By the spring of 1941 the war had shown that the UK fire service required a more co-ordinated response to deal with the conditions created by modern warfare. The government brought into being the National Fire Service (NFS), merging all of the former local brigades and the AFS under one umbrella. The NFS came into being on the 1st August 1941. This new body, the AFS with all 1,638 local authority fire brigades, totalled some 60,000 men and women. The NFS was organised around 40 Fire Forces, London Fire Brigade forming several of these.

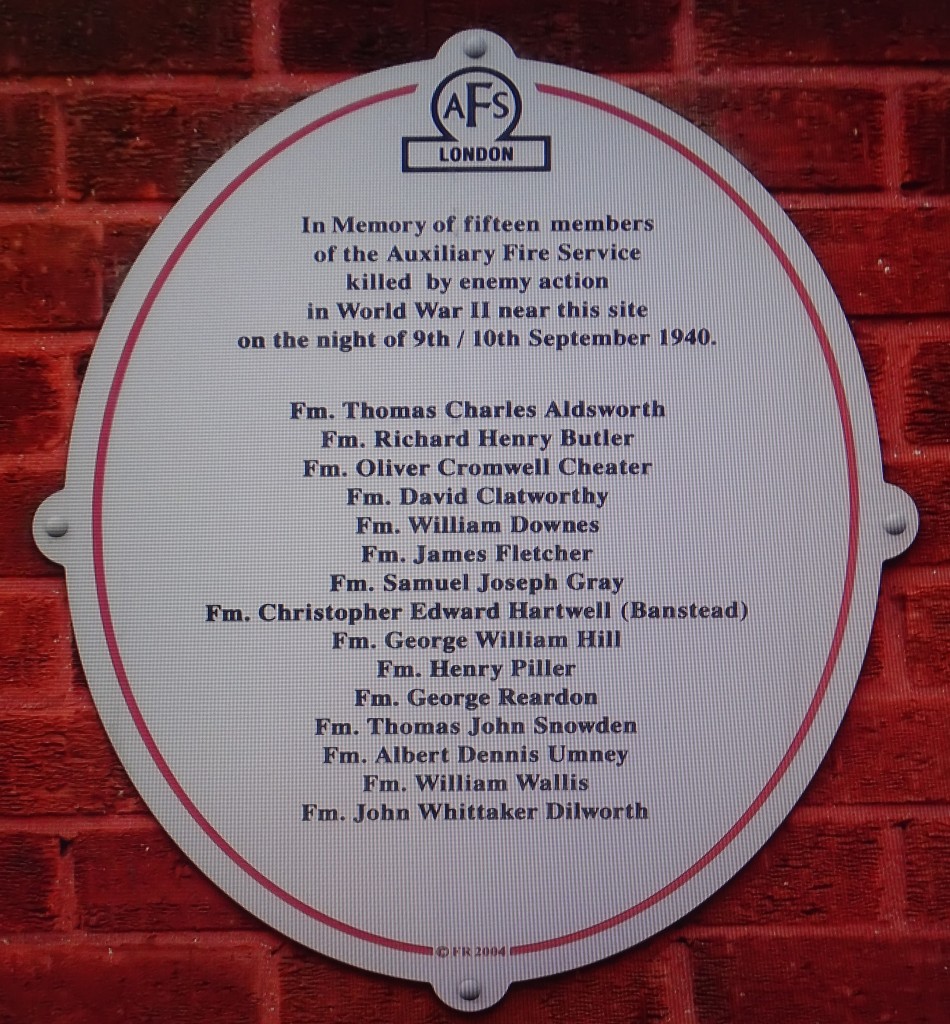

During the Second World War 327 London firemen were killed. The vast majority of those killed were in the early years of the War, most notably during the Blitz and consisted of both men and women of the Auxiliary Fire Service. Many of the locations were they perished are remembered today by the erection of a memorial plaque. Their loss and their sacrific will not be forgotten.

The NFS operated until 1948 when, under the Fire Services Act 1947, fire brigades reverted to local authority control although with now far fewer brigades on a county or county borough council basis. The London Fire Brigade was returned to the London County Council, Middlesex was formed with its own fire brigade and counties like Kent had their own county wide brigade.

With the AFS absorbed into the NFS many continued regulars. Then in 1948 some even found a new career by staying within the Fire Service as peace time firemen.

After eight years in the wilderness, and one year after dissolving the NFS, the AFS was re-established in 1949. It became an integral part of the Civil Defence Corps (CDC)- a civilian volunteer organisation. The ‘Cold War’ and the threat of nuclear Armageddon had created the CDC which would mobilise and take local control of the affected area in the aftermath of a major national emergency; i.e., a nuclear attack.

In London the AFS vehicles, initially, were those that remained in government storage post WWII. From 1953 onwards, purpose bult AFS vehicles came on stream. They were issued painted ‘dark green’ and the era of the ‘green goddesses’ was born. They became a frequent sight on the streets of London. Selected London fire stations housed AFS engines and provided a training base for the crews. AFS crews were occasionally, when on the training nights, dispatched to large fires to gain first experience. The AFS staff trained to be available should they be needed in a national emergency. To this end several times a year they carried out large scale exercises especially in the relaying of large quantities of water over considerable distances. In 1966 AFS men and women came from far and wide to take part in a massive exercise staged in the Port of London. It marked the Tercentenary of the Great Fire of London. It would be their swan song!

Their second stand down came on the 16th January 1968. The Prime Minister, Harold Wilson, announced that the nation’s Civil Defense was to be placed on a care and maintenance mode. The AFS was disbanded on the 31st March 1968. It had survived on the perceived threat of ‘cold war’ fears of nuclear attack. Large scale exercises and mobile columns rehearsed for the probable dire effects of such a nuclear Armageddon or atomic holocaust! But the simple truth was that the radiation from a nuclear attack, the fallout, would have prevented AFS fire crews from getting within 50-100 miles of the scene and then being able to operate safely.

In London the Brigade hosted a farewell reception for the AFS at the Lambeth headquarters. The Chairman of the Greater London Council, Sir Percy Rugg, spoke of the people of the AFS who volunteered unselfishly and with no thought of themselves for the public good. London’s Chief Fire Officer, Lesley Leete (who started his career as a WWII AFS fireman) voiced his regrets at their passing.