Crystal Palace was erected in London for the Great Exhibition of 1851. It was the centrepiece of an exposition constructed in what is now Kensington Gardens. A truly astonishing, prefabricated, design that was created on parkland and with many planted trees inside it. It had been designed in glass, iron and wood by the architect Joseph Paxton at the bequest of Queen Victoria’s husband, Prince Albert. As the exhibition’s focal point it attracted thousands of visitors from home and abroad. The press of the day commented; ‘it could hardly have been a more effective demonstration of advanced British technology.’

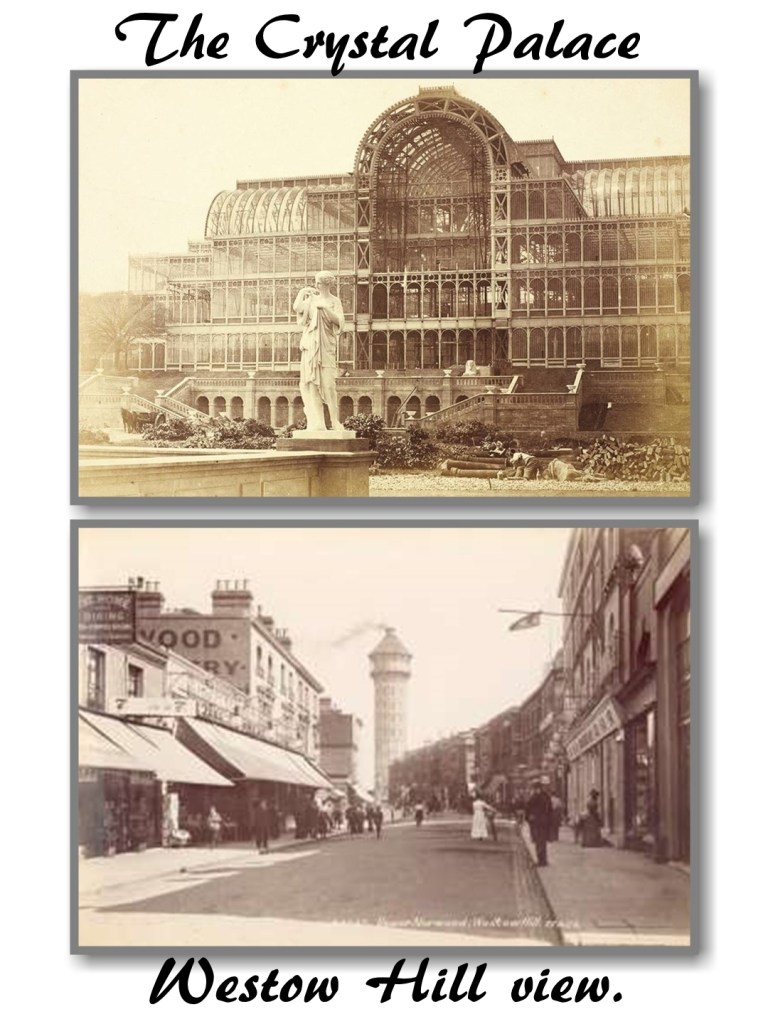

The original ‘Palace’ measured 1,851 feet (564 m) long, with an interior height of 128 feet (39 m) and was, at the time, the largest amount of glass ever seen in a building. When the exhibition closed in 1852 Sir Joseph, as he now was, pointed out that the building could be dismantled and moved somewhere else. It was and relocated to the village of Sydenham, Kent. Paxton ran the whole re-siting operation and the ‘Palace’ was recreated even larger than before. The structure was topped by an imposing Moorish dome in open parkland. From the hilltop, which would take the name of Crystal Palace, it could be seen for miles around.

Twelve years before the Metropolitan Fire Brigade (MFB) was created the new Crystal Palace was formally opened by Queen Victoria in 1854. The new site, comprising gardens and trees, fountains, a maze, life-size figures of dinosaurs, was a great success. Its creator, Paxton, died in 1865 aged 61. Various events vied to be held at the ‘Palace’. They including firework displays, cat and dog shows, cricket and football matches. Crystal Palace even had its own railway station and Sydenham village had developed into a prosperous area in the London suburbs. In the year the MFB was formed a one-off Olympic Games was staged there in 1866. That was also the same year that Crystal Palace suffered its first major fire.

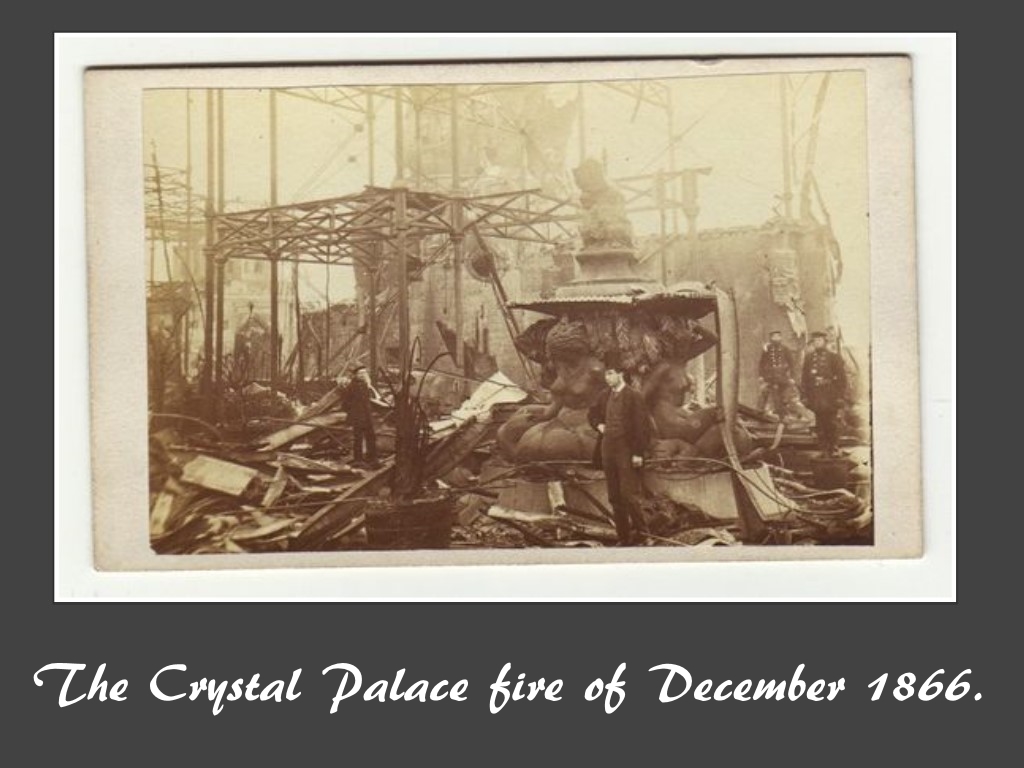

The fire occurred on Sunday 30th December. A fire broke out destroying the North End of the building along with many natural history exhibits. Such was the importance of the site that the MFB’s new Chief Officer, Capt. Eyre Massey Shaw, drove in this carriage from the Watling Street headquarters, in the City of London, to direct operations. As the Crystal Palace Company was underinsured the north transept was never rebuilt and the building was unsymmetrical from then on. In 1892 one person died from a hot air balloon accident and in 1900 another was trampled to death by an escaped elephant.

In 1911, the building hosted The Festival of Empire for George V’s coronation.

Yet despite attracting hundreds of thousands of visitors the revenue raised was still not enough to keep the Palace solvent. It’s much anticipated sale by auction was announced. The scale of its financial problems plagued the Palace, its sheer size meant it was impossible to maintain financially and it was declared bankrupt in 1911. A number of ‘Save the Palace’ schemes came into being and the Earl of Plymouth raised the money to prevent it being sold to developers. Finally in 1913 The Lord Mayor of London set up a fund to repay him and the Palace became the property of the nation.

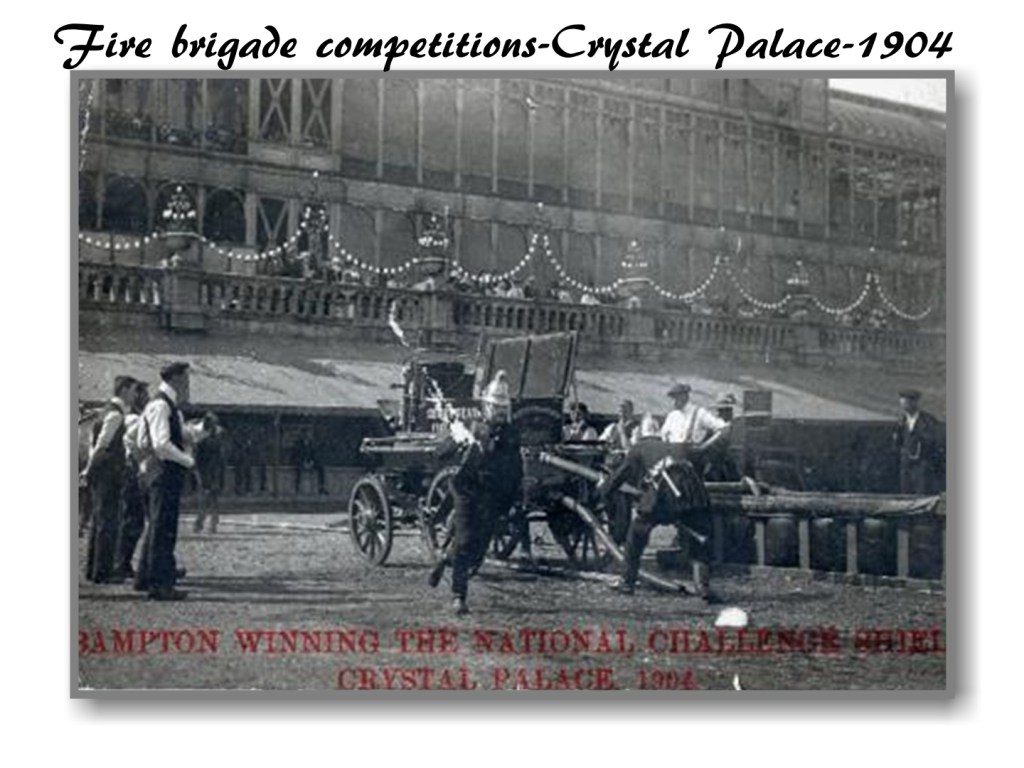

From the time of its reopening on Penge Common in 1854 to 1884, the Palace averaged 2 million visitors a year, hosting a wide range of shows and exhibitions, meetings for numerous societies and organisations, as well as concerts, circuses, pantomimes, and weekly firework displays that only ceased in 1935. It was the venue of many fire brigade competitions too and teams around the country vied for the National Challenge Shield.

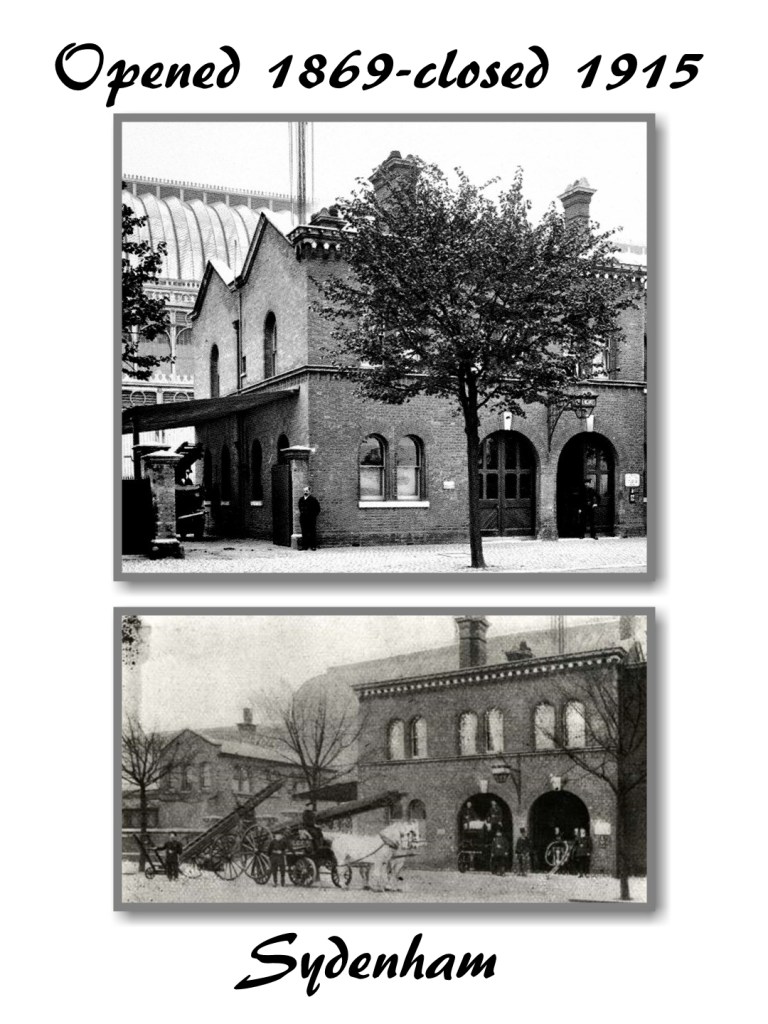

The Sydenham fire station, built by the Metropolitan Board of Works (the forerunner of the London County Council) for the Metropolitan Fire Brigade opened in 1869. It was closed in 1915.

The fire.

On the evening of the 30th November 1936, at about 7.25 p.m. a staff fireman noticed a flame at the rear of the staff offices. Joined by two others they attempted to tackle the blaze but with no dividing walls to resist it, and fanned by a strong northwest wind, the fire rapidly grew in ferocity. The Palace had been almost empty at the time of the outbreak apart from the Crystal Palace Orchestra rehearsing in the nearby Garden Hall. An orchestra member later told reporters;

‘The band didn’t take much notice when told there was a fire in the Palace. But they soon fled after a staff member ran in crying; “Run for your lives! The Palace is blazing!”

It was later reported that just after 7pm on that evening the Palace’s manager, Sir Henry Buckland, was walking in the grounds of the building when he saw a red glow emanating from it. There is no record of him ever summoning the fire brigade. Thick smoke was, by then, bellowing out of the main door and glass was raining down “like red hot treacle” as the orchestra members made a hasty exit. Fortunately that evening a local man was walking his dog past the building when he saw flames inside. Hurrying in, with his dog, he found the firemen vainly trying to extinguish what had started as a small fire but was being fanned by a rising wind. It was he who called the fire brigade, which arrived just after about 8p.m. His call was not the only summons for fire brigade help.

At 7:59 the Penge Urban District Council Brigade received the call but upon arrival found it could not cope and summoned help. Local brigades, Kent, Croydon and London sent more firemen and engines to the scene. The early reinforcements arriving from Beckenham and Thornton Heath. West Norwood fire station, located in Norwood Road, received a street alarm call from Farquhar Road at 8.00pm. (New Cross fire station-a superintendent station- received a further call at 8.02pm.) It was the call to West Norwood that would bring much of the London Fire Brigade into action.

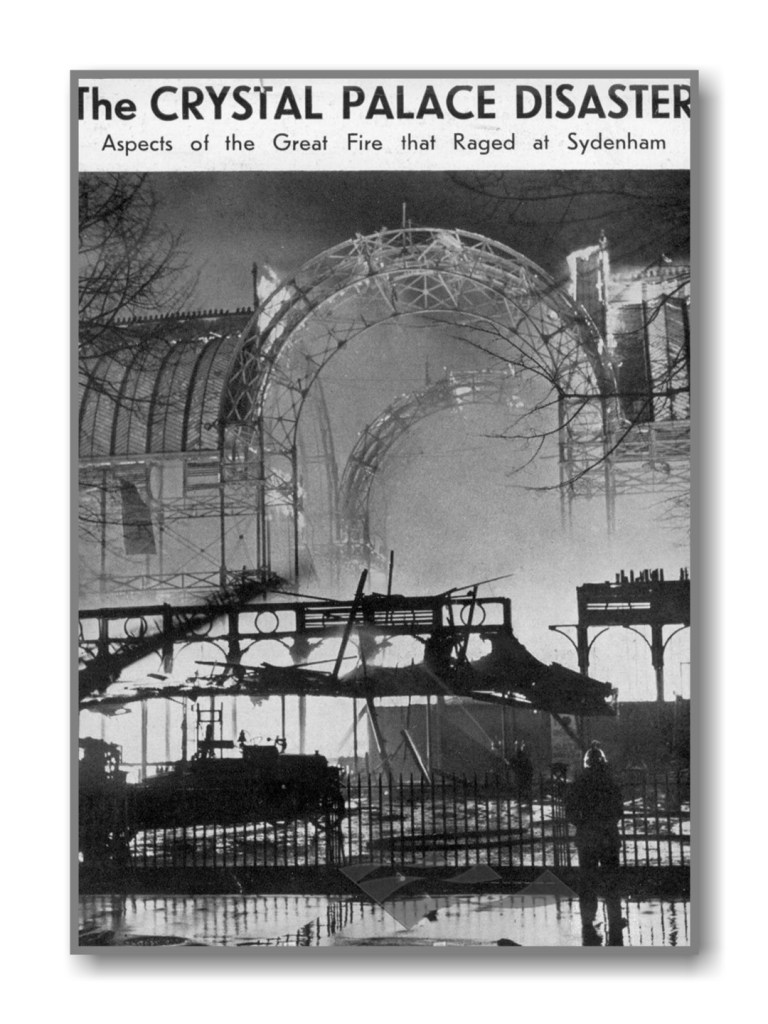

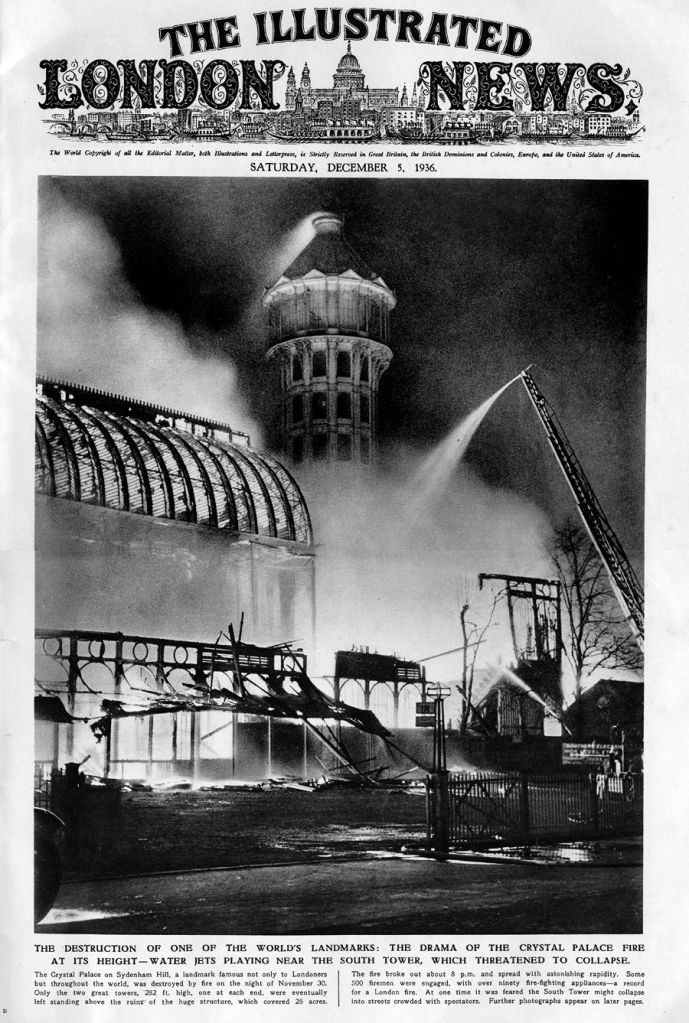

The first London Superintendent to arrive at the blaze made it a ‘Brigade call’. A message that immediately summoned 60 London fire engines to the scene. It was not long before the whole of the Crystal Palace area was ankle deep in inter-woven fire hoses and within an hour of the arrival of the first Penge fireman over 400 fire-fighters were at work. According to some reports, the flames reached 300 feet. The glow could be seen from Brighton and by ships in the English Channel. Hills for miles around were packed with people watching the blaze. Motorcars were also clogging the already chaotic scene arriving from the West End with the well to do who had finished watching the evening performances of London shows.

With the Brigade call message received the Chief Officer, Major Cyril Morris. MC. left the Southwark Brigade headquarters and rushed to the scene where he took over command of firefighting operations from the Chief Officer of the tiny Penge brigade. The Crystal Palace fire raged until midnight. There were serious concern as to the safety of the 275-foot south tower. Not only did it have vast densely populated streets in its shadow but also the top of the tower held approximately twelve thousand gallons of water. Residents of nearby homes were evacuated in fear of it collapsing. Luckily, the London Fire Brigade managed to stop the fire some 15 feet from the tower.

Every effort was made to put the flames out, but they grew stronger and were accompanied by clouds of sparks and fierce explosions. London sent many of its 100 foot turntable ladder fire engines to act a water towers, directing power jets of water into the inferno. Despite the bravery and skills of the firemen, now comprising some 88 fire engines and 438 firemen from four brigades, the building could not be saved. Finally its central transept collapsed with a deafening roar.

Thousands of people flocked to watch the blaze. They came on foot or by bicycle, cars and vans. Even special trains were put on from towns in Kent. Mounted policemen did their best to control the spectators, but they seriously hindered the firemen, as well as causing damage to local people’s properties. When dawn arrived most of Paxton’s masterpiece had been reduced to twisted metal and heaps of ash. The next day all that remained of the former Palace were the two water towers, now blackened with smoke, and a few hundred feet of the nave to the north.

About two hundred of the seven hundred Palace employees received their notice the morning after the fire. Some were re-employed to clear the debris. Six years later the two towers were demolished as they were thought to be an easy navigation point for German bombers. No lives were lost in this blaze and just how the fire had begun was never established.

Rival theories were attributed to the probable cause; one being a cigarette left burning that ignited wooden flooring: another was deliberate sabotage by a disgruntled worker or some sort of extremist! John Logie Baird, the television pioneer, who had a workshop in the building suggested a one of his cylinders might have been leaking flammable gas, which could have been ignited by the watchman’s gas ring. This caused all the other cylinders to blow up like a bomb going off! There was no report of an explosion prior to the blaze by the Palace firemen.

There is some irony about the night the Palace burnt down. The Crystal Palace fire was a more spectacular event than could ever have been dreamt up by the Palace trustees. An irony not lost on many of the national newspapers. The Palace’s swansong brought the largest crowd ever to assemble at the top of Anerley Hill. The event became deeply ingrained in the memories of many Londoners who thronged to investigate the red glowing sky and witness the collapse of their ‘Palace’.

The cause of the fire is remains unknown and there was never an official inquiry into the fire.

I have a conspiracy theory, William Joyce, later known by the whole of Britain as Lord Haw Haw lived close by !

LikeLiked by 1 person

My Grandfather was a member of the Penge Urban District Council Fire Brigade, (1931-41, NFS 1941-48, Kent Fire Brigade at Beckenham 1948-57), he attended this job on the first attendance, as The Crystal Palace was in the Penge Urban District, and outside the London County Council area. Just a small point, the South Tower was dismantled in 1940, and the North Tower was “Blown up” on April 16th 1941, by the Army, as it was thought to be aiding German aircraft as a navigational point.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for that Christopher. I was trying to find an image of the Penge UDC fire station. Do you have any? Kind regards. Dave.

LikeLike

Dave, yes, sorry only just found this, I’ll sort out and send them on another site

LikeLike

my lake father was a member of the LFb ajnd this was his first fire

LikeLike

Thanks for letting me know.

LikeLike

Just a correction….the photo labelled 150-Exhibition Main Building is not the Crystal Palace.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Nick. Appreciated.

LikeLike

The Great Dome was a perfect site to enable several circus acrobats swinging together to thrilll the audience.

LikeLike