What made this such a special time for this aspiring young fireman, one serving at Lambeth fire station, is a matter of some conjecture. Maybe it was just the exciting LFB life viewed through the eyes of this twenty-one year old? A young fireman that was being shown the ropes, and his craft, by the combined experience and wisdom of ordinary people who had chosen the life of a London fireman. Maybe being at a busy fire station helped, but it was also a time of big change. A new ‘Chief’ had brought with him new ways, new ideas. He also brought a fresh new style, one that ordinary fireman seemed to understand and could readily relate too where it really mattered-out on the fire ground. However, it was also a time of considerable wider industrial unrest, even fraught at times. But it never seemed to be personal, there never seemed to be a lynch mob baying for the new Chief’s blood.

It was only after his premature departure from the Brigade, many considered under a cloud, that I can honestly say I got to know this man a little better. Ever so briefly in the early eighties and on a more regular basis in the late nineties. Joe was not a Londoner. His service with the LFB was only as its Chief Officer, yet despite the manner of his departure he only ever referred to his tenure in office with warmth and genuine affection. He always remained loyal to its ‘firefighters’ and had worked hard, even in retirement, to support them via the then named Benevolent Fund.

Personally, I remain convinced that Joe was a man of his time. A man gifted with a common touch. A man I remain proud to have served under. A man who should have been referred to as SIR JOE…If there is a league table of LFB Chief Officers’ he is up there with the very best. I do not feel the LFB will ever see his like again, but who knows given how the new one is doing? So a reminder of the man-Joe Milner.

Joe was born in Manchester in October 1922. He was the son of a Manchester labour and his affinity to the working man (and woman) remained with him throughout his career and beyond it. Leaving school at 14 he worked for a short time with a firm of gas engine manufacturers before joining the Manchester Corporation’s Transport Department. (As what was never recorded.)

With the imminent outbreak of war Joe had joined the army in 1938 at 16 years of age. He served in the Royal Corps of Signals until his 18th year when he transferred to the Kings (Liverpool) Regiment in 1940. From 1942 until 1946 he fought in India and Burma. In 1944 Private Milner was a member of Orde Wingate’s Long Range Pentation Force (The Chindit’s) and was flown into Burma by Waco gliders. His were the Broadway Landings, one of three selected sites to fight and harry the Japanese. Milner arriving at Broadway in the March. 600 further sorties followed bringing in more men, by which time about 9,000 Chindits (supported by over 1,000 animals) were present in Burma. Between June and July the Chindit’s sustained heavy casualties and were slowly pulled out of Burma. The last Chindit left Burma on 27 Aug 1944. Milner’s tour of duty was meant to last only 90 days but it was 5 months before the survivors, debilitated by malnutrition and disease, were finally pulled back into India. (No other units throughout World War II were kept in the field, deprived of any relief or recuperation, and are comparable to what the Chindit’s had endured.)

In 1945 Joe Milner once again returned to Burma. This time he was a member of the War Graves Unit and his, and his companions, task was to recover and properly bury the bodies of fallen comrades. He was working there for seven months.

Having been de-mobbed in 1946 Joe Milner applied to the Northumberland Region where he did his National Fire Service (NFS) recruit fireman training. Recruit Milner won the Under Secretary of State’s prize for the best recruit. Joe Milner was a fireman in the last months of the NFS. With the return of fire brigades to local authority control in 1948 Joe Milner, who had risen in rank, first became part of the Middlesbrough fire brigade and then transferred to the North Riding of Yorkshire Brigade before finally transferring into the Manchester Fire Brigade in 1950. It was the same year that he passed his Graduates exam in the Institution of Fire Engineers (IFE).

At 29 Milner was selected in 1951 to become a Station Officer in the Hong Kong Fire Brigade, as it was called then. The following year he passed his Membership exams of the IFE. Asked later why he has chosen Hong Kong to apply for he said; “I felt the call of the East. But more important I had a hunch that both Hong Kong and its fire service were due for radical transformation. I want to be in on the ground floor of a development like that”.

He was proved to be right and the credit went to him for bringing about many of those radical, and successful, changes. He saw the service grow from just 500 firemen to 3000. It became the second largest fire-fighting force in the Commonwealth and one of the world’s most efficient. During his first four years Joe Milner was in charge of the Kowloon District before running the Inspection Branch (later renamed the Fire Prevention Branch). Between 1955 and 1961 he was appointed a Divisional Officer, then District Officer before becoming the Deputy Director of Fire Services. He was awarded the Queen’s Fire Service Medal in 1962.

Appointed Director in 1965 Joe Milner was a major force in bringing about change and modernisation to the Hong Kong Fire and Ambulance Service. Not least in his list of significant achievements were the introduction of the Brigade’s ‘Search and Rescue’ Division, which accounted for 10% of the Hong Kong force. He also introduced new smaller sized fire stations rather than the few big ones plus an attendance criterion of six minutes.

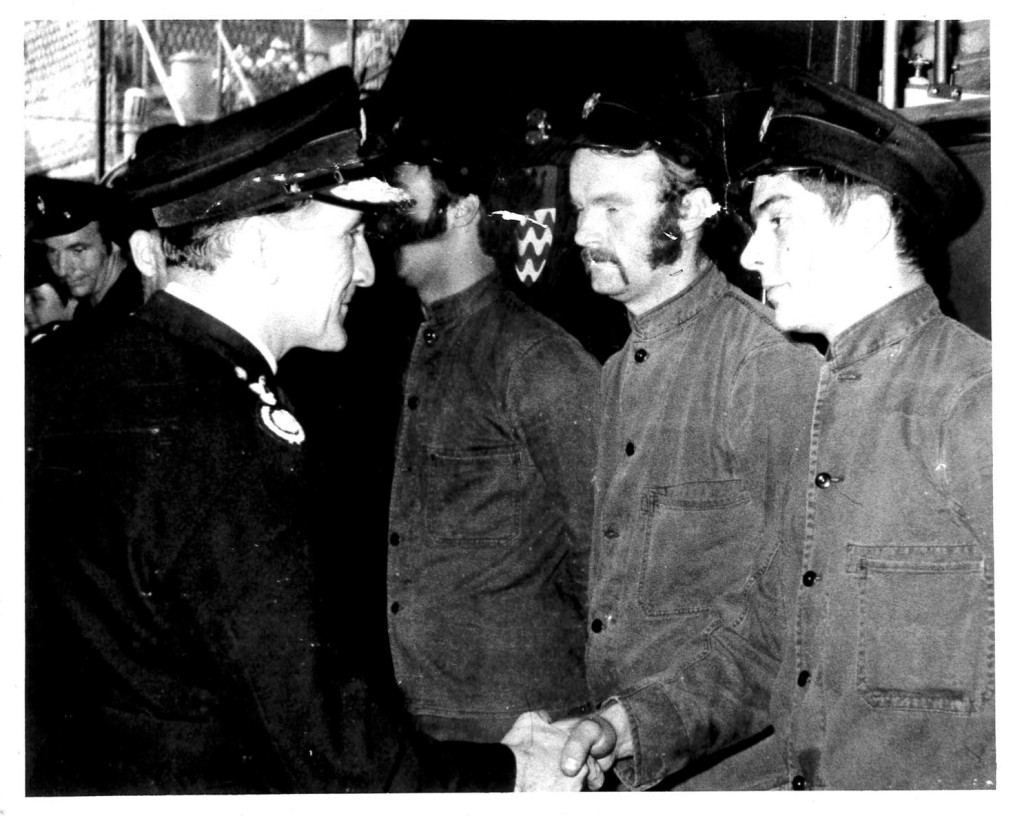

Armed with an impressive CV and a proven track record the Fire Brigade’s Committee of the Greater London Council selected Joe Milner to replace Leslie Leete, the retiring LFB Chief Officer. He took over the London Fire Brigade in June 1970 at the age 47. A sea change had come to the Brigade. Many would soon discover their new Chief to be a forthright man who did not mince his words. He was in stark contrast to the outgoing Chief who had given the impression of being particular uncomfortable in the company of the lower ranks. Joe, as he was to be affectionately called, was not tall and was slightly built. He had the appearance of a marathon runner although he was in fact an avid walker. Those on night duty in Lambeth’s watchroom would regularly see him leaving the Headquarters’ lobby around 5 a.m. for his daily six-mile constitutional and with his favourite pipe in his mouth. He would return some ninety minutes later occasionally popping into the fire station watchroom to chat with the dutyman. (A practice that would have been a complete anathema to the previous post holder.)

For those around the Brigade then reading the new Chief’s profile, produced for the in-house magazine and listing Joe Milner’s war record, it was akin to something taken from of the Boy’s Own Annual. Soon many would meet the man in person as he travelled around the eleven Divisions, and being seen frequently on the fire ground looking, learning, and gathering intelligence plus, one of Joe Milner’s greatest strengths, listening to the views of his London firemen and their officers.

One of his first actions did not set the world alight but nevertheless set the tone of his tenure. He added the word RESCUE to the Brigade’s fleet of Emergency Tenders. His aim was to remind the public of what the LFB did and the variety of services it performed. Things did not go all his way as his desire to consider a complete name change to ‘London Fire and Rescue Service’ never saw the light of day.

In that first year his in-tray contained many issues requiring his urgent attention. But some things were beyond his control. Those early seventies had maintained the momentum of the late sixties with its growing political and industrial unrest. It was making its presence felt in every part of everyday life. The widespread national dock strikes (that were to sound the death knell of London’s docks) gave rise to dire economic effects. The then Labour government lashed out in response at its traditional stronghold of support, the Unions. Inflation had risen sharply by the end of the previous decade as the reduced buying power of London firemen’s meagre monthly wage more than demonstrated. Joe’s arrival coincided with an increasingly powerful trade union movement sweeping the nation (it also saw the removal of Labour’s Harold Wilson and the arrival of the Tory’s Ted Heath as Britain’s Prime Minister). This increased power and the demands by the Unions for better working conditions was felt within the fire service too.

It was following on from yet another major dock strike the country faced yet a further local authority dustmen’s strike. Once again London’s communities were up to their knees in tons of uncollected refuse. The results of this action was not lost on London’s inner city population or its many fire stations crews who were having to cope with the health and fire hazards caused by the consequences of the continuing battle for better pay and conditions demanded by the dustmen’s unions. Their employers resisted these demands supported by the Government’s unseen controlling hand. Rubbish rapidly accumulated all over again at the capital’s designated dumping areas. Night after night fire engine crews travelled around central London fire stations’ grounds dealing with these proliferation of fires or standing-by whilst the home station’s crews were dousing putrefying rubbish fires piled ten feet high in some cases. Leicester Square became a notorious “emergency” rubbish dump and the stench, after just a few days, was almost overpowering. South of the river much less salubrious locations were used to pile the uncollected garbage. But regardless of location, clambering over this mixture of rotting and smelly household and commercial waste was equally unpleasant regardless of where it stacked. Joe Milner would, together with other senior officers, take to the streets to see at first-hand the conditions that theirs firemen were having to endure.

For organisational leaders, and Joe Milner was but one, the seventies were an extreme decade as regards its industrial relations record. The extreme left dominated many Unions, including the Fire Brigades Union (FBU). Progress and proposed changes in the London Fire Brigade’s working practices were challenged and obstructed. The Unions opposition not necessarily supported by the whole of the London FBU membership, but in a show of hands, Union activists (better described as ‘militant’) would often carry the day.

The first, in a series, of the FBU “emergency only disputes” hit the Brigade during the middle of the Milner era. London firemen answered just nine-nine-nine calls and at some of the more militant stations appliances were taken “Off the run” for the most trivial of reasons. Maintaining adequate fire cover became a major issue at times for Chief Milner. This new type of fire brigade “industrial” action grew incrementally throughout his time in office. Finally, but after Milner’s sudden departure in 1976, the first national strike involving firemen started in November 1977. It lasted for sixty-nine days.

Just after a year in office, and in August 1971, Joe Milner became one of only two Chief Officer’s in modern times to command a fifty pump fire in the greater London area. CFO Milner actually commanded his whereas he predecessor merely attended it. Joe’s fire was one of the fiercest and most difficult fires that the post-war London Fire Brigade had to face. It lasted nearly thirty hours and involving all three watches. The scene of the blaze was at Wilson’s Wharf, Battle Bridge Lane just off Tooley Street in Bermondsey. SE1. It was ironic that this should be the same location that cost the life of London’s first Chief fire officer, Superintendent James Braidwood, when in 1861 he was buried under a collapsed wall in a warehouse blaze that took several days to bring under control. (Braidwood’s brigade being called the ‘London Fire Engine Establishment’.)

Wilson’s Wharf had been built on the site of that first devastating fire, part of the Hays Wharf Companies great rebuilding scheme, and had opened in 1868. Starting life as a coffee and cocoa wharf it later became the company’s first wine and spirit bottling department. Just over a century later it now lay unoccupied, having previously undergone conversion to a refrigerated warehouse and major cold store. The six-storey warehouse had an irregular shape and sat tightly wedged between other wharfs. On the riverside was a wide vehicular jetty where previously goods and products had been delivered to its one hundred and fifty foot wide riverside access. It was also one hundred and fifty feet from this side of the building to the far side, which faced Tooley Street. Various raised open and covered iron bridges were connected to surrounding wharves.

A small fire had started during the removal of plant. Unable to stem the rapidly developing fire with an extinguisher, contractors beat a hasty retreat from the building leaving their oxy-acetylene cutting plant in situ. It was sparks from their hot cutting that had ignited combustible tape on the pipe-work insulation. It had spread to the building’s insulation material itself, four-inch thick very flammable expanded rubber. Even as the contractors were running out of Wilson’s Wharf and local crews drew closer, the hot and smoky atmosphere was being trapped inside this disused cold store. Its windows and loopholes had been bricked up, making the building a veritable fortress thus turning large parts of the complex into a vast brick oven. The fire superheating the interior.

In the space of forty-five minutes pumps went from fifteen, to twenty, and then thirty. Command of the fire changed hands so quickly that no single plan of action could be properly implemented until the Chief Officer Milner finally took command at 16.16 pm. He faced daunting problems, taxing even his considerable know-how of commanding major incidents from his time in Hong Kong. He had all his Headquarters’ principal officers at his disposal, including Deputy Chief Harold Chisnell. It would take their combined experience and expertise to direct operations at this incident, which was now extremely serious, due to the complex layout of the building, the thickness of the walls and lack of access points. The heat build-up, deep inside the structure, was likened to a potter’s kiln operating at its maximum temperature.

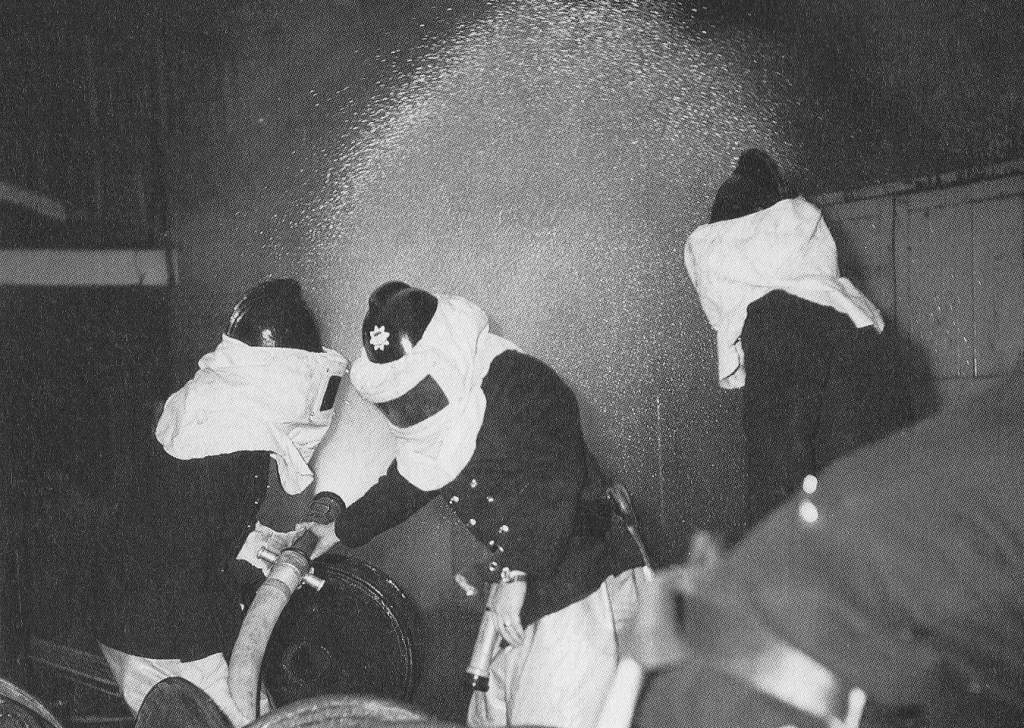

Despite the tenacity and doggedness of his firemen, the tremendous heatand smoke posed major problems for any of the crews fire-fighting to establish a bridgehead to counter the blaze. Contractors working alongside firemen tried to break open some of the bricked up windows at third floor level with elementary breaking-in gear, club hammers and cold chisels, but little or no progress was made. Meanwhile those BA crews that had made exploratory forays into the building were slowly being forced back out by conditions so severe that their exposed skin blistered. So intense was the fire at this stage that complaints of smoke drifts were received from as far away as Bethnal Green and there were reports of smoke drifting into some Underground stations in the City. (London Bridge Railway Station was adjacent to the incident.)

With a conflagration of such magnitude Joe Milner considered that only two courses were open to him: One was to concentrate on subduing the fire in main warehouse and arresting its development to the adjacent blocks. This would require him to committing crews to extremely hazardous and punishing conditions. Furthermore it would require a total commitment in the order of some 80 pumps! The result would be to denude large areas of London of any fire cover for a protracted period. (Of note; during the course of this fire the brigade dealt with 222 calls to other incidents in the capital.)

His second option was to abandon the efforts to subdue the fire in main warehouse and to concentrate on surrounding the fire and confining the spread to the area bounded by Battle Bridge Lane, English Ground the River. The success of Milner’s strategy depended on allowing the fire to break through the roof of the central warehouse and reduce the lateral transmission of heat and smoke by ventilation. The danger Milner faced being that once the fire broke through the roof there would be a serious threat to surrounding property and adjacent area from radiated heat and flying firebrands.

Following discussion with his command officers Joe Milner decided to adopt the second option. At 5.12 p.m. he ordered that pumps be increased to 50.His operation proved successful and by 1.30 a.m. the next day the fire had been reduced to the fourth and fifth floors and entry had been effected by BA crews. Although heavy smoke was still being encountered, steady progress was made throughout the day and it was possible for the Chief to send the “stop” message at 8.30 p.m. on the second day of the fire. The firefighting operations involved the use of twenty-three jets, eight radial branches, and one high expansion foam unit and in excess of 200 one-hour Proto BA sets using an estimated 315 oxygen cylinders.

The damage to the complex consisted of three-quarters of all floors severely damaged by fire, the remainder severely damaged by fire, heat, smoke and water, one half of the roof severely damaged by fire, heat and smoke. His stop message read;

From the Chief Officer. Stop for Wilsons wharf, Tooley Street.

A range of unoccupied buildings of 1, 2, 3, 5 and 6 floors and basement, covering an area of 200 x 300ft. 2/3rds damaged by fire 1/2 of roof off. 20 jets 8 radial jets 3 TL monitors high ex foam. Breathing apparatus.

TOO: 2038

Joe Milner’s brigade was operationally very busy throughout his tenure in the seventies. In fact during Joe Milner’s six year reign the Brigade dealt with more 20 to 35 pump fires than the previous decade or the next one. But the Chief had new operational worries to consider. Its operational workload was further added to that year by the “Troubles”. The IRA bombing campaign came to London in October 1971. The Post Office Tower (now called the BT Tower) was an IRA terrorist target. The bombing, although not resulting in any fatalities, did cause the closure of the building to the general public for many years to come. Joe Milner, like so many others, watched these events unfold on national and local news. However, the threat of becoming caught up in this new breed of incident was not only promoting discussion and speculation amongst station personnel, it was also increasing the concerns of wives, partners and firemen’s families. It seemed the IRA could make an attack on any high profile London landmark and the Chief was very aware, when on duty, his crews were concerned about their family members, many of whom worked in the capital and could become an innocent victim of this hate campaign. Such things were beyond his control and his firefighters had a job to do, but his concern for the wider fire brigade family was every present whenever he meet with his crews. (The IRA would bring brought twenty-nine separate bombings to the capital whilst Joe Milner was the Chief in the early 1970s.)

By the end of that year Joe Milner had prepared plans for a radical shake-up of the way the Brigade was managed. His proposal were summited to the GLC’s Fire Brigade Committee and were accepted without modification. At its heart was a new Operations Branch headed by ACO Don Burrell. They were supported by the Technical, Planning and Development Branch headed by ACO Trevor Watkins, plus a Mobile Group (whose role was to check the way policies and procedures were being implemented) lead by ACO Ernie Allday. Additionally, the Fire Prevention Branch retained its existing role and there was revamped Training and Recruitment Branch.

On the evening of the 30th October 1971 Chief Joe Milner gave a ground breaking address to the Brixton Rotary Club at Kings Georges House, Stockwell Road in SW 4.He nailed his colours firmly to the mast in publicly acknowledging the value and esteem with which he personally held his officers, the men and women of the LFB. Such was the importance of his moving and heartfelt talk his complete address was later repeated in a special supplement to the London Firemen magazine.

He was not the only ones to make comment on the workings and people of the London Fire Brigade. In a highly unusual break with normal protocols the Fire Service Inspectorate, who were notoriously tight-lipped about what they observed in their Brigade inspections, commented most warmly on the enthusiasm of all ranks. They confirmed Joe Milner’s own belief that the moral and the ‘esprit de corps’ within the Brigade were high.

London, under Joe’s stewardship, lead the British fire service with its work in implementing a Hazchem Code, which was considered to be ground breaking work and much credit deservedly went to the late Charlie Clisby, then a Deputy Assistant Chief Officer. It was adopted across the emergency services during 1972. In the same year Milner directed that the Brigade launch a TV advertising campaign warning of the dangers of portable paraffin heaters. Heaters that had directly responsible for multiple fatalities and serious house fires. It was the first time a UK Brigade had used TV advertising in this way.

Then the ‘Three-Day Week’ presented special problems for Joe Milner and his principal management team. They were one of several measures introduced across the United Kingdom by the then Conservative government to conserve electricity, the generation of which was severely restricted owing to strike and other action by coal miners and the aftermath of an oil crisis. This resulted in widespread blackouts over the winter of 1973 to 1974. The phased blackouts left fire stations (and everyone else for that matter, except essential services such as hospitals) without power for three to four hours at a time. Mobilising was severely affected and orderings had to be given over the radio network. Fire stations had no stand-by electrical generators and the resultant use of emergency lighting in homes (i.e. candles) lead to a number of serious fires.

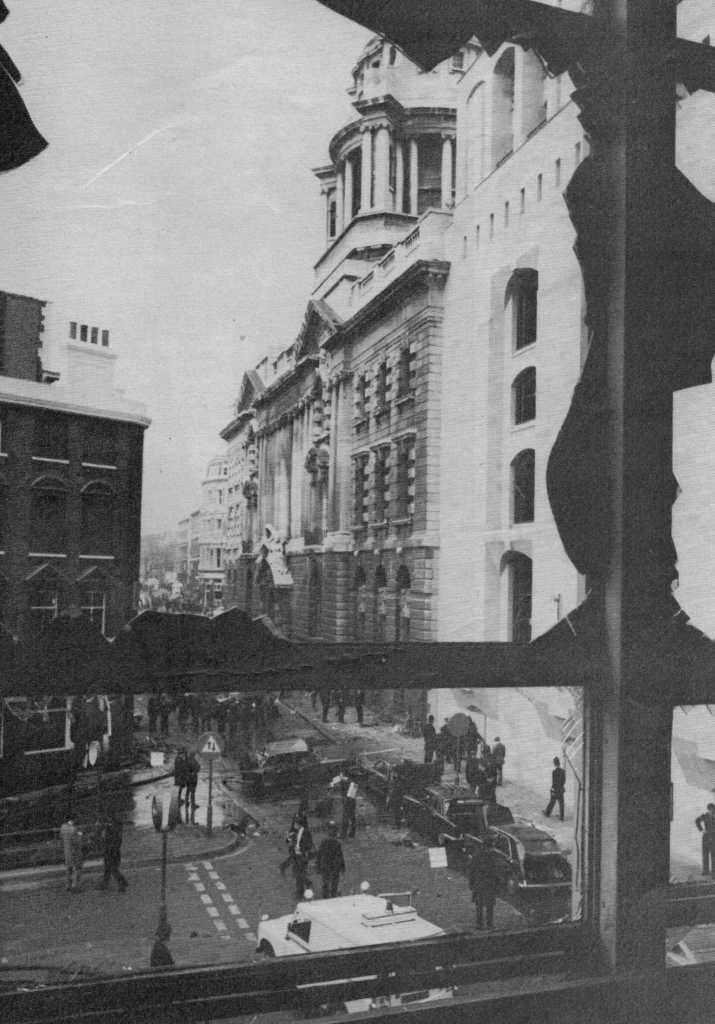

The bombing of the Old Bailey law courts, at the heart of the British justice System, in March 1973 marked a dramatic shift in the tactics of the IRA in their attempts to bomb their way to achieve their political ends. The IRA exploded two car bombs in the heart of London and injured over two hundred innocents. Sadly, one man died, although not through the direct impact of the bombing butfrom a fatal heart attack. The bombers had callously chosen a day when thousands of commuters were forced to drive into central London becausestrikes had hit the capital’s public transport services.

It was St Bart’s Hospital that bore the brunt of the one hundred and sixty or so patients that were either taken there or who made their own way to the hospital’s emergency treatment department. The hospital had had no warning of the bombing or of the impending arrival of so many patients. Accordingly its procedures for implementing a major accident plan could not be used. Most of the walking wounded required treatment for cuts and abrasions, but nineteenindividuals were admitted and nine required surgery. There was much behind the scenes top level discussions on the role and safety of fire crews given the escalation in tactics of the Irish terrorists. Milner’s view remained firm that where public safety was concerned his crews would remain committed to all lifesaving duties and in all circumstances. His view widely supported by the Brigade’s rank and file.

It was in the early months of 1974 that Joe Milner charged the Brigade to embark on its most intensive recruiting drive since the creation of the AFS in 1938. You could not look anywhere without seeing advertising space taken up in the national and local press, even on commercial television and radio, encouraging men to join the London Fire. Brigade recruitment posters were even pasted on to the sides of our fire engines!

Staff shortages were bad and getting worse. Appliances were being taken off the run at an increasing rate because there were not enough men to crew them. Normal manning was quickly reduced to minimum levels and the firemen were constantly being ordered out to other stations to make up the shortfalls. The FBU contested that some firemen were spending more time riding engines at the surrounding stations than at their own. More firemen were needed for the introduction of the forty-eight hour week, a reduction of eight hours from the existing fifty-six hour week. But Joe found himself operating in a very competitive market place. The Post Office, London Transport and the Metropolitan Police were all wanting extra staff and just as urgently. However, the brigade of the early 70s remained almost totally a white dominated operational work force. The desire to see a reflection of the multiracial society that London was rapidly becoming sadly did not feature in its recruitment campaign. But many non-white applicants did apply and “times they were a changing.” Colour did become an issue but not in the way you might think…Joe would see in the introduction of ‘Yellow’ fire helmets first and then yellow leggings.

By 1974 Joe Milner was really getting into his stride. It was the year that his promise of more breathing apparatus for his firemen was delivered. Compressed air (CA) breathing apparatus sets were introduced into pump-escapes and proto sets on pumps reduced to two per appliance with two additional CA carried. It was the same year which he introduced the Chemical Incident Unit into the operational fleet. It would attend the increasing number of chemical incidents and be mobilised to all radiation incidents.

Joe Milner’s only operational fatality on his watch occurred at the end of 1974. Tragically Fireman Hamish Harry Pettit lost his life at the Worsley Hotel fire which also claimed the lives of six other occupants. It was in the early hours of Friday 13 December 1974 that two separate fires were deliberately started in the Worsley hotel. The Worsley Hotel comprised a series of interconnecting houses and were 4 or 5 storeys tall. The hotel was located at 3-19 Clifton Gardens in Maida Vale, W9. The Worsley was used by the hotel industry to house both hotel and catering employees, many of whom came from aboard, and were either working or training in Central London hotels.

As further London crews arrived along with increasingly more senior officers to direct operations most of the occupants were accounted for as the immediate rescues were completed. The operations moved from one of rescue to fighting the fire. Crews took heavy hoses through the doors from the street and off ladders pitched to upper windows. One of these firefighting crews, 3 firemen led by a Station Officer, entered a second floor room to search out the seat of the fire. Whilst in the room several of the floors above them, now weakened by the extra load of the partially collapsed roof and the weight of a large water tank, came crashing down on the crew. The devastation appeared concentrated on that one room. It was not known initially how seriously the injuries to those trapped in the collapse might be. The release of their trapped colleagues became an immediate priority. It proved to be a most difficult and protracted rescue operation. One by one the 3 of the trapped men were released (2 firemen with serious burns and the Station Officer with a serious back injury). Tragically when the body of the 4th fireman was found he was declared dead at the scene. It was the body of the 26 year old probationer fireman, Hamish Harry Pettit, who had attended the fire with Red Watch A21 Paddington.

Chief Milner was no shrinking violet when it came to turning out from his Greenwich quarters to any incident. In addition to the 30 pumping appliances, 3 turntable ladders, 3 emergency tenders and other specialist vehicles attended this incident Joe Milner saw at first hand the efforts directed to saving life and building. The “Stop” message was despatched at 08:02 that morning, but damping down went on for some days. The fire proved to be the largest fire in Central London that year.

The Worsley Hotel fire was also the first major incident dealt with by the Wembley control room after computerized mobilising system had been commissioned earlier that week. Another of Milner’s improvements to the Brigade mobilising practices. He had closed the Lambeth Control room the same year.

For a man not shy to recognise the bravery and commitment of his fire crews this incident nevertheless resulted in one of the largest number of fire brigade bravery commendations from a single incident with four of the firemen subsequently receiving national gallantry awards from the Her Majesty the Queen. The highest bravery award in the London Fire Brigade is that of a Chief Officer’s Commendation. Joe Milner ‘COMMENDED’; Fireman Hamish Pettit (Posthumously), Temporary Sub Officer Roger Stewart and Fireman David Blair (West Hampstead), Sub Officer Ronald Morris and Leading Fireman Peter Lidbitter (Westminster), Station Officer Neil Wallington and Fireman Raymond Chilton (Paddington), Temporary Leading Fireman Eric Hall (Soho), Temporary Divisional Officer John Simmons (Brigade HQ) and Assistant Divisional Officer Tom Rowley (A Division HQ).

He also issued ‘Letters of Congratulation’ to; Assistant Chief Officer Trevor Watkins. DFC. KPFSM (Brigade HQ), Assistant Divisional Officer Gerald Clarkson (Brigade HQ), Assistant Divisional Officer Roy Baldwin (A Division HQ), Station Officer Keith Hicks, Temporary Sub Officer Ian Macey, Firemen Donald Clay, Edward Temple and Peter McCarlie (Soho), Fireman David Webber (Paddington), Fireman David Harris(Action) Acting Leading Fireman Alan Trotman (Belsize) and Fireman Daniel O’Dwyer (Manchester Square).

In 1975 Joe Milner’s name appeared in the Queens New Year Honours list. He was made a Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (CBE).

The following month he actually meet the Queen but not at the Place, Her Majesty came to see him at the Lambeth headquarters in February. After meeting GLC dignitaries, including former London fireman ‘Paddy Henry who was now the Chairman of the Fire Brigade’s Committee, Joe Milner escorted the Queen into the Officers’ Club where she met representative crews and officers who had attended IRA bomb incidents over the previous couple of years. Typical of the man he moved away from Queen, after introducing each of the eight crews, to allow those being presented to talk to the Queen one on one.

The last day of February was a Friday and whilst Joe Milner was in his Lambeth officer the 08:38 service from Drayton Park on the London Underground Northern line (Highbury Branch) had left one minute late. It was formed of two three-car units of 1938 LTE rolling stock. On arrival at Moorgate station the train failed to slow, passing through the station platform area at 30–40 mph before entering the 66 feet (20 m) long overrun tunnel with a red stop-lamp, a sand drag and a hydraulic buffer stop. The sand drag only slowed the train slightly before the train collided heavily with the buffers and impacted with the terminal wall.

It was declared a Major Accident by both the Brigade and the London Ambulance Service. It was the LFB’s most difficult special service incident in over a decade. It was London’s worst-ever Tube disaster. The crash left the station in total darkness and threw up a huge amount of soot and dust. Joe Milner both at times commanded the incident and maintained a regular presence throughout the initial rescue and then recovery phase.

The five day rescue operation involved 1324 firemen, 240 policemen, 80 ambulance men, 16 doctors and numerous voluntary workers and helpers. The last body to be brought out of the tunnel was that of the driver, Leslie Newson, a 56 year old husband and father of two children. It was London’s Chief Fire Officer who famously quoted ‘MY THOUSAND SELFESS HEROES’, in dedication to the literal 1000 firefighters who spent 5 days rescuing survivors.

It was in the early summer that Joe Milner ‘upped sticks’ and resigned from the London Fire Brigade. There was no warning of his imminent departure, but his was always his own man so it is to those who were part of the upper echelons at the time to say if he walked of his volition or was PUSHED? What is known is that that Joe’s first wife Bella died that year and he married Anne in the later part of 1976. So maybe he choose love over career, a career where he was seen as Caesar and there were too many Brutus’s on Lambeth’s principal floor.

In the September issue of the London Fireman the acting Chief, Don Burrell, gave not a mention to the departed Joe Milner, his achievements, his commitment to London’s firemen or even a ‘wish you well in your retirement’. The comments were churlish to as the least! If there was ever a ‘leaving do’ for Joseph Milner the powers that be never thought to cover the event in any future addition of the in-house magazine…

Postscript.

In his retirement Joe became an ambassador for the then named Fire Services National Benevolent Fund (The Firefighter’s Charity). He happily took the invitation to return to London, to attend a presentation following a sponsored Paris to London marathon row in the summer of 1981, and to accept a substantial cheque on behalf of the fund. He never uttered one ungracious word about his departure from the Brigade unlike some in principal rank who had kicked up a stink because Joe had been invited.

He travelled around but finally settled in Norfolk. Joe was a regular attendee to the then Retired Senior Officers Mess Club, under the watchful eye of its President Brian ‘Bill’ Butler. Despite the considerable travel distant Joe loved those evenings and the opportunity to swing the lamp and tell a tale or two. I was in regular contact with Joe then and never once did he comment on the manner of his departure, or of those that probably orchestrated it. He was a remarkable human being.

Joe wrote a novel, based on his own war time experiences, that was published in 1995. To Blazes with Glory was a Chindit’s tale, it was no doubt his tale too.

Joe died at his home in Caston, Norfolk, on the 13 January 2007. His Funeral Service was held on the 29th at Holy Cross Church in Caston. The London Assembly purely noted ‘the recent death of former London Fire Brigade Chief Fire Officer, Joseph Milner CBE, QFSM.’ There was no comment by any Elected Member or Brigade officer on how much the man had achieved and done of the reputation of the London Fire Brigade.

Dave Pike. (Sept 2017)

Thanks again David for sharing the history of CFO JOE MILNER . Without past men like him I wonder where we would be. There will always be the political men who are selfish and only interested in their wee world

LikeLike

Totally agree Andrew-a privilage to have known the man in later years and to have served under him. Regards. Dave.

LikeLike

First met Joe on a flight to Tenerife he asked if he could sit next to me to have a smoke got chatting he asked what I did for a living I told him he said I’m in the LFB you may have heard of me I’m your new Chief Officer great man.

LikeLike

Great tale Roger. A genuine privilage to have got to know Joe better in later years.

LikeLike

Whilst I totally agree with you that Joe Milner was an excellent Fireman and Chief Officer , I would just like to remark on your comments re my father the late Don Burrell .In your piece you suggested that my father made no mention of Joe Milner’s departure from the LFB or the contribution he made .I would just like to point out that , whilst my Father was Joe Milner’s DCO , there were many times that my Dad unequivocally supported Joe Milner .I can indeed pay testament to this as I was living with my parents at the time in Lambeth HQ and was privy to many events that occurred and saw for myself how much my Dad liked and supported him.Yes,in hindsight ,maybe my Dad should have said something about Joe Milner’s tenure as Chief Officer but there was a lot of pressure emanating from Whitehall at the time and I can assure you that that piece in the London Fireman was censored .I have heard comments about my Dad and yes I know he wasn’t perfect by any means but , as his daughter , i feel compelled to state that in no way did he attempt to bring about Joe Milner’s resignation.

LikeLike

Hi Jan, First (and most importantly) I had the greatest respect for your Dad. From my early days at Lambeth, dispite the guff in rank, we bumped into each other on a regular basis-often I got the rough edge of his tongue for being in the wrong place at the wrong time! But he never held a grudge. Whilst at Southwark Dad and I worked a jet together at a thirty pumper in Wapping Wall. He was an ACO then and his comment was, nice to be a fireman again for 5 minutes…In retirement we met frequently when he popped into Lewisham to have a drink with BWB-in fact they got ‘rat-arsed’ and I recall him losing his false teeth down the loo!!!. But he was always a gent. As to Joe, well that is certainly different to what the late Gordon White told me. There was no censoring of any submitted piece, because as you probably know it was Gordon, in the main, that wrote the words of the Chief…Nothing was published. I would never infer that your Dad did anything of the sort-Joe brought about his own dimise and choose Anne over career. But it will always remain a fact that Joe’s time with the Brigade (and so many achievements) went unrecorded at the time of his departure. That, sadly, happened on Dad’s watch as acting Chief. I feel the words reflect the times. Kindest regards. Dave

LikeLike

Hi Dave,and thank you for getting back to me. Yes ,you’re totally right about Gordon White and I probably wasn’t clear enough when I said about the magazine piece being censored – I meant it in as much as my Dad had been ‘advised’ in no uncertain times from senior politicians of the day to adhere to speaking of the ‘ 1976 Fire Brigade dispute’ and ,if memory serves me correctly , The Fireshow of that year ( I did try to substantiate this but I believe Martin has the relevant magazine!)

I appreciate this all happened a long time ago but I just wanted it put on record that my Dad had a very good working relationship with Joe and respected the Fireman and Chief he was.

Finally,yes ,I also remember the tale of the missing false teeth as well !! BWB and my Dad – not always a good combination – bless them both .

Best Wishes ,Jan

LikeLike

Jan, just a footnote regarding Dad and the Crystal Palace Fireshow. All credit to him he was front and centre at the show, despite the work to rule by the FBU. Southwark had put on the fire scene and London Weekend Television supplied the set, we supplied the dam. I a moment of weakness (or bravery) Dad came over to thank the crews…with no malice I would add-Dad was headed to the dam for dunking! “Hold my watch Pikey” says he and in he went!!! Great repect for the man Jan, and his children. LFB to the core even if Martin did go rouge. 🙂

LikeLike

As you say Dave, Joe was a good Chief & a good friend in his retirement, we sunk a few pints in the local pubs & spun a few yarns as well as chatting about life. RIP Joe, you were the best !!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Standing up for Rights and commented:

I am proud to have Served from 1968 under CFO Milner throughout his service in the London Fire Brigade. The firemen I know held this man in the highest regard for his outspoken support of firefighters against fierce opposition from the authorities over the pay dispute. This helped to raise the value and status of firemen, and helped end the first national fireman’s strike. Dave Pike’s article is an important record of the life of a Hero.

LikeLike